Show interactive timeline

Cairnbulg to Inzie Head — Dalradian migmatites

T. E. Johnson and S. Fischer

An illustrated PDF download is available from the Aberdeen Geological Society website

Purpose

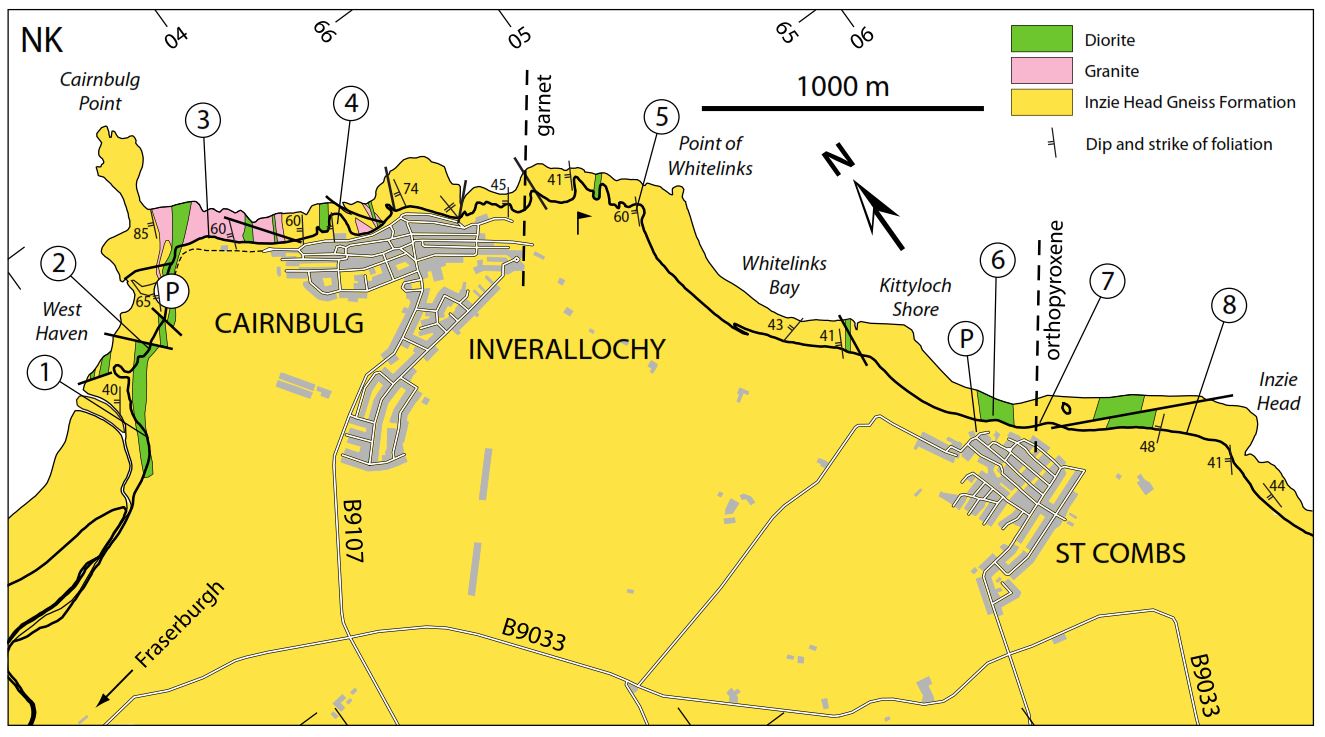

To examine migmatised metasedimentary rocks of the

Access

The exposures lie along the shore between West Haven on the east side of Fraserburgh Bay and Inzie Head, south of St Combs

Entering the village(s), follow the road round to the left onto Main Street, and continue onto Shore Street and to the small harbour at the end of the track where there is ample parking. Although adequate

exposures can be accessed at high tide, a lower tide allows access to cleaner rocks. Large sand waves migrate seasonally, affecting in particular the southeastern end of the section (localities 6–8), where

many of the exposures can be buried. The excursion can be completed in half a day (4 hours) and logically follows

Introduction

The metasedimentary rocks on this excursion form part of the

Migmatised metapsammites underwent relatively low degrees of partial melting (metatexites) and occur as large rafts in which bedding and an earlier spaced cleavage is preserved. Migmatised metapelitic and metasemipelitic rocks underwent extensive partial melting in which pre-anatectic (sedimentary) structures were largely destroyed. These rocks are diatexites containing numerous fragments of metasediment (schollen) and discontinuous layers rich in biotite (schlieren).

At the lowest-grade (northwestern) end of the section metapelitic migmatites contain cordierite and biotite with sillimanite, quartz and feldspar. Further upgrade (southeast) garnet appears, recording the transition from upper amphibolite facies to granulite facies conditions. At the highest grades, in the core of the Buchan anticline (Read & Farquhar, 1956), the migmatites lack sillimanite and garnet and contain pseudomorphs interpreted as former orthopyroxene (Johnson, 1999). Along with transitional upper amphibolite to granulite facies rocks south of Deeside (Baker & Droop, 1983; Goodman, 1990), the gneisses here are amongst the highest-grade regionally metamorphosed rocks in the Dalradian. However, the rocks have experienced pervasive retrogression and the original high-grade minerals have largely been replaced by chlorite and white mica.

The section is bounded by geophysically defined faults/shear zones trending NE through Fraserburgh Bay and Whitelinks Bay (Kneller, 1987). These may be the extension of the regional shear zones that surround the Buchan block (Ashcroft et al., 1984) and which may have provided the H2O required for the high degrees of partial melting and retrogression (Johnson et al., 2001). Gravity and magnetic anomalies suggest a mafic/ultramafic mass at shallow depth beneath this area and upper zone cumulates crop out in shallow pits only 1 km inland (Trewin & Rollin, 2002). These mafic/ultramafic masses probably provided much of the heat required for migmatisation. Many of the granulite facies metapelitic rocks in the aureole of the Huntly mass (Droop et al., 2003) have assemblages similar to those around Inzie Head. Peak metamorphic temperatures in both localities were > or >> 800 °C at crustal depths of around 15–18 km (Johnson et al., 2001; Droop et al., 2003).

Itinerary

Locality 1. West Haven [NK 0305 6515]

From the harbour carpark, walk west along the track for 600 m and onto the beach to flat lying wave-washed exposures on the westernmost part of West Haven on the east side of Fraserburgh Bay. West Haven is a natural collection point for sea-borne detritus, and the rocks at localities 1 & 2 are partially to completely covered in a heady mix of rotting seaweed and worse.

The westernmost exposures consist of medium-grained, dark green quartz-diorite (mainly hornblende–plagioclase–biotite–quartz) cut by veins of granitic pegmatite. The NW margin of this diorite body can be located near the eastern end of the sandy beach where the track ends

The metasedimentary gneisses are mostly metapelitic and metasemipelitic migmatites in which pre-existing structures have largely been destroyed (i.e. they are diatexites; Figure 2). Wispy discontinuous layers of biotite (schlieren) and fragments of diffuse metapelite and metasemipelite and more angular blocks of calc-silicate and metapsammite (schollen) are abundant. The pale grey quartzofeldspathic leucosome occurs in patches and as veins that exhibit complex cross-cutting relationships

Locality 2 [NK 0325 6541]

The marginal relations of the diorite are well displayed where the sheet seen at locality 1 re- emerges from beneath the grassy bank. At its margins the diorite is penetrated by, and mingled with, leucosome derived from the surrounding migmatites

Locality 3. Cairnbulg granite [NK 0367 6561]

Return to the harbour and walk east to exposures at the top of the beach just to the north of the isolated house. The rocks are dominated by fine-grained weakly to unfoliated leucogranite with abundant pink veins. In places the granite contains mafic schlieren and the diffuse schollen, and there is no clear distinction between granite and leucosome-rich diatexite migmatite. This granite is an extensive body several hundred metres in width. It is intruded by, and mingled with, several diorite sheets (exposed, for example, at low tide around the harbour wall), suggesting the coexistence of felsic and mafic magmas.

Locality 4. Janet's Craig [NK 0408 6539]

Return to the vehicle and drive back past the first row of houses in Cairnbulg. Take the left fork onto Shore Street and find a parking place. Walk onto the rocky headland (Janet's Craig) opposite the only buildings on the northern side of the road.

The rocks here are dominated by migmatised metapsammites. The metapsammites occur as large boudinaged rafts several metres in length in which a spaced pressure solution cleavage is clearly preserved. Overall, the amount of leucosome in these rocks is significantly lower than at West Haven, and the original bedding is easily traced through the rafts (i.e. the migmatites are metatexites). The rafts (and bedding) are aligned subparallel to the variably developed foliation.

Some 150 metres back to the northwest

Locality 5. Point of Whitelinks [NK 0495 6476]

Continue to follow the road southeast along the shore into Inverallochy (to the uninitiated there is no obvious boundary between these villages) and follow the pot-holed track round the northern edge of the golf course and park where it ends (a total distance of around 1.8 km). Walk southeast and onto the broad flat-lying rock pavement around Point of Whitelinks to superb exposures of diatexitic migmatites

The metapelitic migmatites are schollen diatexites containing abundant grey cordierite-bearing leucosome and a second paler-coloured leucosome that contains abundant dark-green rounded clots rich in chlorite. These clots are up to 10 mm in diameter and represent pseudomorphs after garnet; many retain cores of fresh garnet

Garnet first appears some 350 m or so to the northwest of this locality marking the position of the garnet isograd in the migmatites (Johnson, 1999). The coexistence of garnet and cordierite in metapelitic rocks is generally regarded to record granulite facies conditions, and the garnet isograd thus also marks the amphibolite to granulite facies transition.

A generalized reaction appropriate to the formation of garnet in these rocks is: biotite + sillimanite + quartz = garnet + cordierite + K-feldspar + melt. This reaction probably records temperatures in excess of 750 °C and would have resulted in the production of a significant quantity of melt over a small temperature interval. Although exposure is limited, sillimanite does not occur in higher-grade rocks to the southeast.

Locality 6. St Combs [NK 0555 6339]

Drive back through and out of Inverallochy and, at the next crossroads, turn left onto the B9033 towards St Combs. Drive into the village and follow the High Street, turning left into Gordon Street and parking in the small car park at the end of this road just as it bends sharply left. Walk east onto the sandy beach and to the obvious wave washed exposures of dark coloured rock.

The exposures are of a large diorite body containing abundant veins of granitic pegmatite. The diorite here (as elsewhere in the section) is dominated by hornblende, biotite, plagioclase and quartz. No primary clinopyroxene occurs, although clots of hornblende may have replaced this mineral. The diorite generally is fractured where intruded by the pegmatites. However, finer-grained veins of granitic leucosome have diffuse contacts with the diorite suggesting they mingled as magmas.

Locality 7 [NK 0568 6327]

Walk southeast along the beach a further 200 m. The rocks here are coarse-grained granoblastic migmatites containing a chaotic mixture of leucosome, schlieren, small schollen, (altered) cordierite, biotite and garnet

Garnet and orthopyroxene (pseudomorphs) coexist in the northwestern part of the coarse granoblastic migmatites, but garnet is not found in metapelitic rocks much more than 50 m or so further southeast. A generalized reaction appropriate to the formation of orthopyroxene (and the disappearance of garnet) is: biotite + garnet + quartz = orthopyroxene + cordierite + K-feldspar + melt. This reaction probably records temperatures in excess of 800 °C at low pressures (4–5 kbar) and would have resulted in a further pulse of melt production.

Locality 8. Inzie Head [NK 0607 6292]

Exposure from here down to Inzie Head to the south consist of residual migmatites containing abundant biotite and (altered) cordierite and orthopyroxene

References

Baker, A.J. & Droop, G.T.R. (1983). Grampian metamorphic conditions deduced from mafic granulites and sillimanite K-feldspar gneisses in the Dalradian of Glen Muick, Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, London 140, 489–497.

Droop, G.T.R., Clemens, J.D. & Dalrymple, D.J. (2003). Processes and conditions during contact anatexis, melt escape and restite formation: the Huntly Gabbro complex, NE Scotland. Journal of Petrology 44, 995–1029.

Johnson, T.E. (1999). Partial melting in Dalradian pelitic migmatites from the Fraserburgh – Inzie Head area of Buchan, north-east Scotland. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Derby.

Johnson, T. E., Hudson, N. F. C. & Droop, G. T. R. (2001a). Melt segregation structures within the Inzie Head gneisses of the northeastern Dalradian. Scottish Journal of Geology 37, 59–72.

Johnson, T. E., Hudson, N. F. C. & Droop, G. T. R. (2001b). Partial melting in the Inzie Head gneisses: the role of water and a petrogenetic grid in KFMASH applicable to anatectic migmatites. Journal of Metamorphic Geology 19, 99–118.

Kneller, B.C. (1987). The gneisses of Cairnbulg. In: Trewin, N.H., Kneller, B.C. & Gillen, C. (eds) Geology of the Aberdeen area. Scottish Academic Press, Edinburgh, 107–111.

Read, H. H. & Farquhar, O. C. (1956). The Buchan Anticline of the Banff Nappe of Dalradian Rocks in north–east Scotland. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, London 112, 131–156.

Stephenson, D., Mendum, J.R., Fettes, D.J. & Leslie, A.G. (2013). The Dalradian rocks of Scotland: an introduction. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 124, 3–82.

Trewin, N.H. & Rollin, K.E. (2002). Geological History and structure of Scotland. In: Trewin, N.H. (ed). Geology of Scotland. The Geological Society, London.

Acknowledgements

TEJ is indebted to Richard White for funding fieldwork and to Giles Droop for comments.

Appendix — addition photographs

06/12/2013