Show interactive timeline

18 Stonehaven to Findon: Dalradian structure and metamorphism

B. Harte, J.E. Booth and D.J. Fettes

An illustrated PDF download is available from the Aberdeen Geological Society website

Purpose

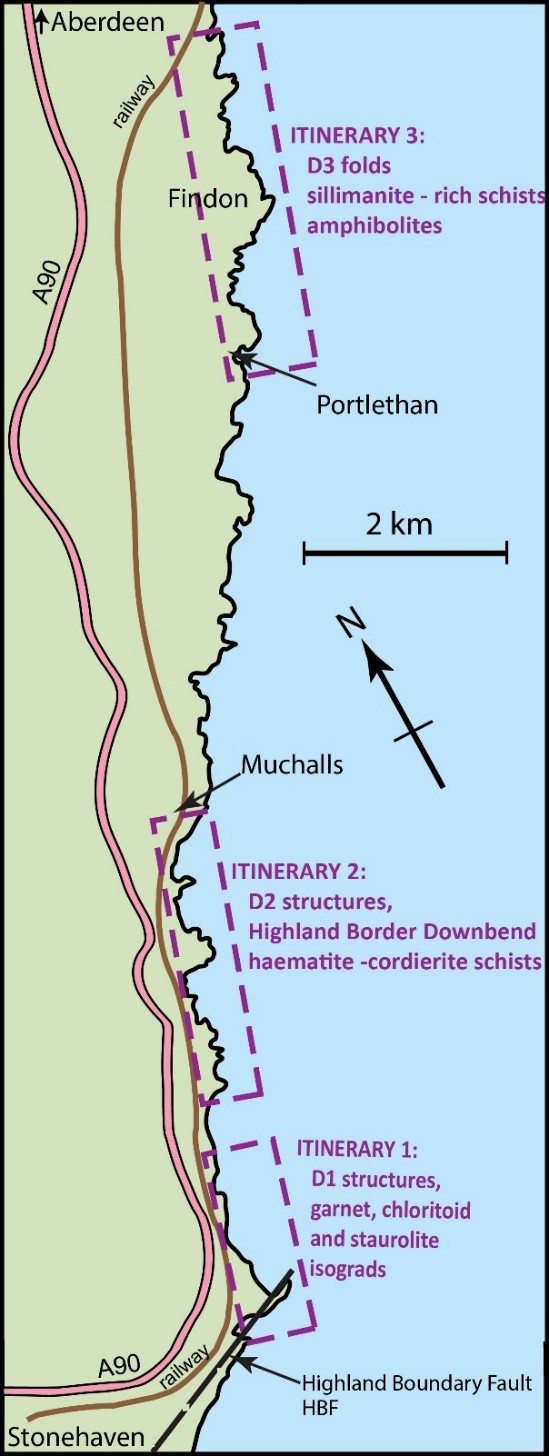

To examine the structure and metamorphism of the Dalradian rocks of the Kincardine coast from the Highland Boundary Fault near Stonehaven northwards to the environs of the village of Findon, about 13 km south of Aberdeen.

Access

The excursion is divided into three coastal itineraries. Low tide is an advantage, but by no means essential for all the localities described (see details in individual itineraries). Many of the localities described are along the shore line, which is normally backed inland by cliffs (often 50 to 60 metres high). Descending the cliff line to reach the shore sometimes involves walking steep and narrow paths, which can also be slippy in wet weather. Walking across raised boulder beaches is also arduous in places.

Introduction

This guide covers the major part of the coast section between Stonehaven and Aberdeen, and is concerned with rocks belonging to the

The Kincardine coast section also illustrates well the progressive incoming of different phases of deformation in the Dalradian rocks as one proceeds north from the Highland Boundary Fault. Five phases of deformation have been recognised in the section (Booth 1984) but since the fourth phase has no regional correlative it is treated as a subphase of D3 and not discussed separately here. All other phases are similar to those found in Glen Esk and elsewhere to the southwest in the southern and central Highlands (Tanner et al. 2013; Stephenson et al. 2013). Therefore, D1 relates to the formation of the major Dalradian nappes, whilst D4 relates to the formation of the major Highland Border Downbend structure, which runs NE–SW in the Dalradian close to the Highland Boundary Fault (Harte et al. 1984). The south to north traverse of the Stonehaven section passes into progressively deeper and more complex structural regimes. The initial section south of the Limpet Burn is characterized by D1 folds and associated cleavage (S1). North of this point the D1 structures are strongly modified by subsequent deformations. D2 structures which are absent south of Limpet Burn increase in intensity northwards such that bedding (S0), S1 and S2 commonly form a composite fabric. S3 fabrics are present intermittently along the section but significant D3 folds only appear north of Portlethen Bay. D4 folds are present throughout the section verging towards the Highland Border Downbend whose axis lies in the Tilly Tenant – Castle Rock o' Muchalls area

The three itineraries in this guide are summarized below and subsequently described in detail with designated localities in each itinerary. To complete all three itineraries in a single day is not possible if the rocks are to be examined carefully. Visitors may also wish to combine the first itinerary in this guide with final section of excursion 23 (see below).

Outline of itineraries

Features to be examined in each of the itineraries are summarized below.

Itinerary 1. Skatie Shore to Limpet Burn (Localities 1–7,

To see the succession of metamorphic mineral assemblages from biotite to staurolite zones (including the occurrence of chloritoid). To examine the D1 fold system and see that the S1 cleavage is continuously downward facing; although the position of the F1 fold axes can be constrained by bedding-cleavage relationships, only in rare cases can an actual fold closure be seen. Examples of possible D3, D4 and post-D4 folds and cleavages may be found.

This itinerary may be easily combined with visiting localities 10 to 15 in the excursion guide by Gillen and Trewin (2015) available on the Aberdeen Geological Society website. Locality 10 of Gillen and Trewin is the unconformity of Old Red Sandstone sediments on the

Itinerary 2. Muchalls Area (Localities 8–11,

This itinerary is largely concerned with structural features. Several phases of minor folding are observed. D2 structures, which were scarce in the areas of itinerary 1, are now found; and there is particular emphasis on the D4 folds and the major D4 structure of the Highland Border Downbend.

Itinerary 3. Portlethen to Clashrodney (Localities 12 to 15,

Stops are suggested at three main points (Portlethen village, Findon and Findon Ness, Blowup Nose and Clashrodney) to see aspects of minor structures and observe the transition from high grade staurolite zone to sillimanite zone (without staurolite). Notes are also given on granitic injection sheets in pelites-psammites and amphibolites at Blowup Nose/Clashrodney on the south side of the Cove granite.

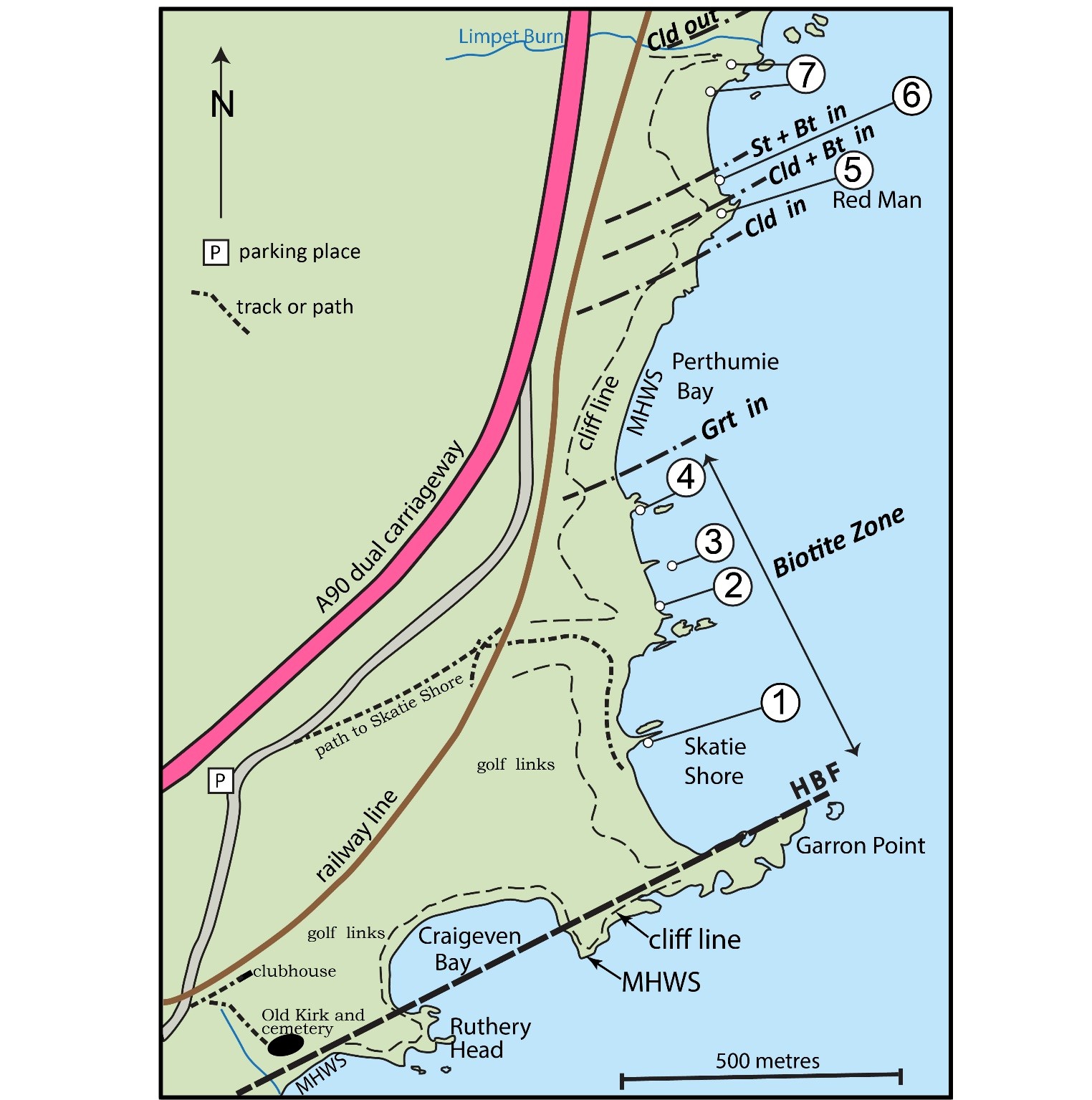

Itinerary 1. Skatie Shore to Limpet Burn (Figure 2)

The whole of this itinerary may be done from a single parking place (P on

Park in the layby

If you are planning to do the end part of the Excursion covering the

To proceed directly to the first locality described in this itinerary, walk about 80 m up (north) along the road from the parking area, and then take the path to the right – a small sign says the path goes to Skatie Shore and the Highland Boundary Fault. The path leads down through the trees into a gully (glacial overflow channel) heading towards a major viaduct for the railway. At

Locality 1. Skatie Shore [NO 8906 8782]

At this locality a prominent but dissected ridge runs from the cliffs into the sea. The rocks here are typical of the

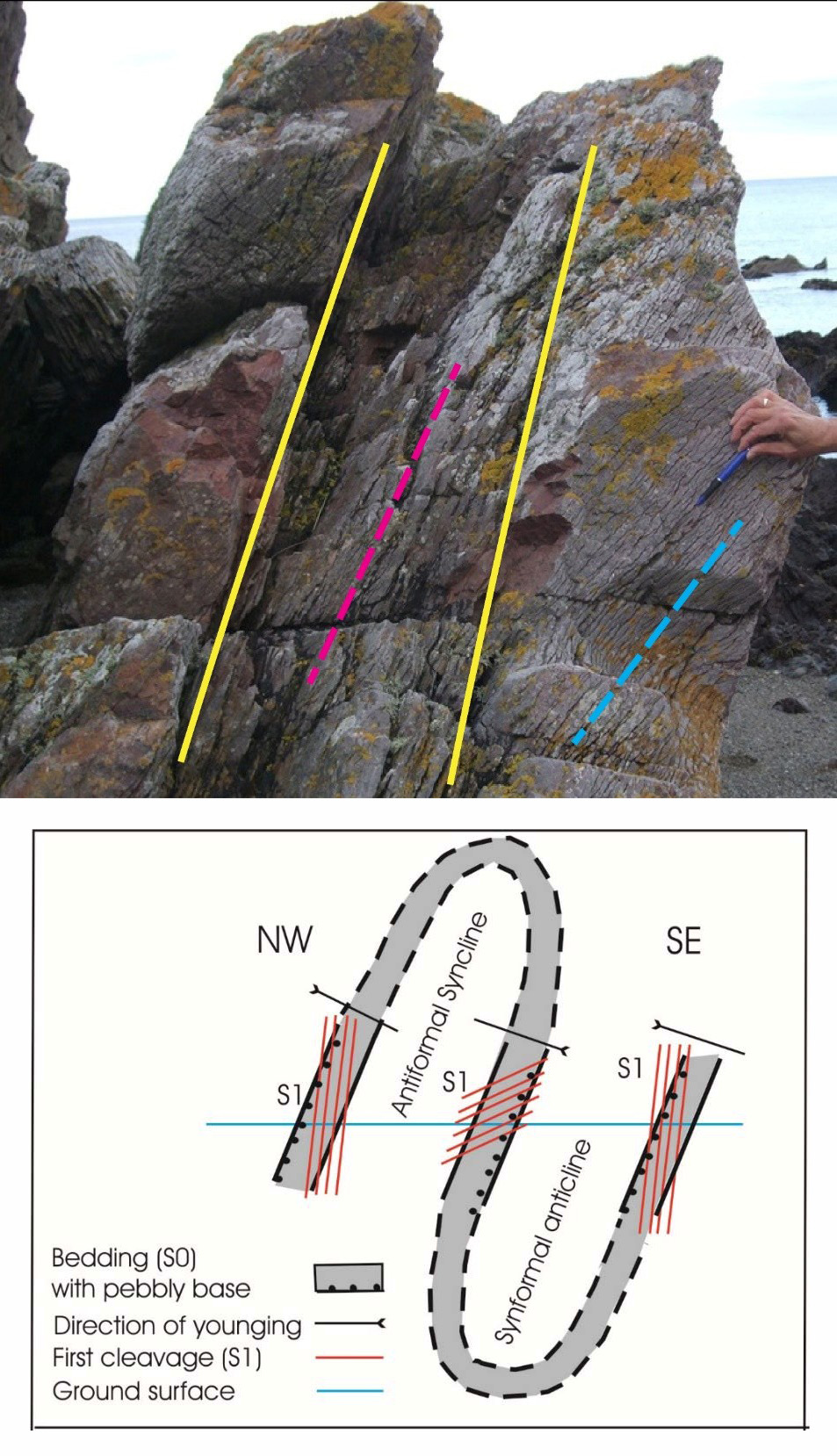

Cleavage, bedding and graded bedding are particularly well seen on WSW-facing vertical rock faces between high and low tide. Here bedding typically dips at 70° to the NW whilst the S1 pressure solution cleavage in grit units dips at 55° to the NW. Grading in pebble beds indicates that the beds young to the north, hence the S1 cleavage is downward facing (Shackleton 1957).

A few metres to the south, across a small sandy patch in exposures near to the high tide mark, there are beds younging south (i.e. the opposite direction), but here, although the angle between cleavage and bedding is much smaller, cleavage dips more steeply NW than bedding. Thus S1 is still downward facing, but between these two localities there lies an F1 synformal closure — it is thus a synformal anticline as the beds young away from the core of the fold (Figure 3b). Although several folds can be identified in the section these are generally evidenced by younging reversals and related changes in the cleavage/bedding angle; actual fold closures are difficult to see.

Locality 2. [NO 8911 8807]

Localities 2, 3, 4 are in the southern part of Perthumie Bay, just north of where the path from the parking area meets the beach (see above). In this area there are extensive rock exposures in the tidal zone, and those close to the high tide mark are often quite clean. At locality 2, two D1 fold hinges may be found with patient searching. The first is close to the western (high tide) margin of the intertidal exposures, and is only a few cm across; the more seaward of the two is more easily found and is a much larger example, having a wavelength of 2 m. The folds here close to the east and west with very steep axial plunges and S1 can be seen to fan around the fold axes. These are rare exposures, actually showing D1 fold hinges — please do not hammer them.

By examining the S1/S0 intersection lineation you can see that it is parallel to the plunge of the folds. By analyzing such intersections it is possible to show that the fold plunges vary from near horizontal to vertical.

Locality 3. [NO 8914 8817]

This locality is a gully through an upstanding rock mass on the wave cut platform. The rocks form a sea stack at high tide and are only accessible at below half tide. Whereas many of the rocks in the intertidal zone are difficult to observe because of seaweed, etc, the rocks in the gully are quite clean and it is possible to see three ages of cleavage.

Although all three cleavages may be seen at several places along Skatie Shore and Perthumie Bay, the main S1 cleavage is generally the most preponderant one by far. This locality is particularly good for distinguishing various cleavages — the basic relations of cleavages are seen on the ENE side of the gully. The S1 cleavage is essentially subparallel to bedding and dips steeply to the north. S3 is developed in semi-pelites and takes the form of a quartz ribbed segregation cleavage, which is sub-vertical at this locality. S4 is found weakly developed in semi-pelites but is better seen in pelites; it is a mica schistosity or grain alignment cleavage, dipping moderately NW. Along the southern side of the ridge, seaward of the gully, there are many fine examples of graded pebbly beds which show that these beds young to the north.

Locality 4. [NO 8905 8823]

This locality is marked by the seaward protrusion of the grassy platform (raised beach) at the base of the cliffs. There are several thick pelitic beds developed immediately around here. In them one can find porphyroblastic biotite, clearly visible to the naked eye. Roughly parallel to bedding is a fine S1 schistosity which is crenulated by S4 which dips moderately steeply NW.

Near the high tide line to the north and south of the grassy feature there are many fine examples of graded bedding and some of the largest angles between S1 and bedding.

In the region from a little north of locality 4 to locality 2, it is possible to find several reversals of the younging direction, and changes in the relative inclination of bedding and cleavage. However, it usually takes a little time to get used to distinguishing bedding and cleavage and picking out the graded bedding. With time, several fold axes may be tied down to a few metres but fold closures are not easily seen.

Locality 5. Red Man [NO 8925 8872]

From locality 4 proceed northwards along the shore following rough paths close to the boundary between the shingle beach and the grassy area of the raised beach. As you approach the northern end of Perthumie Bay

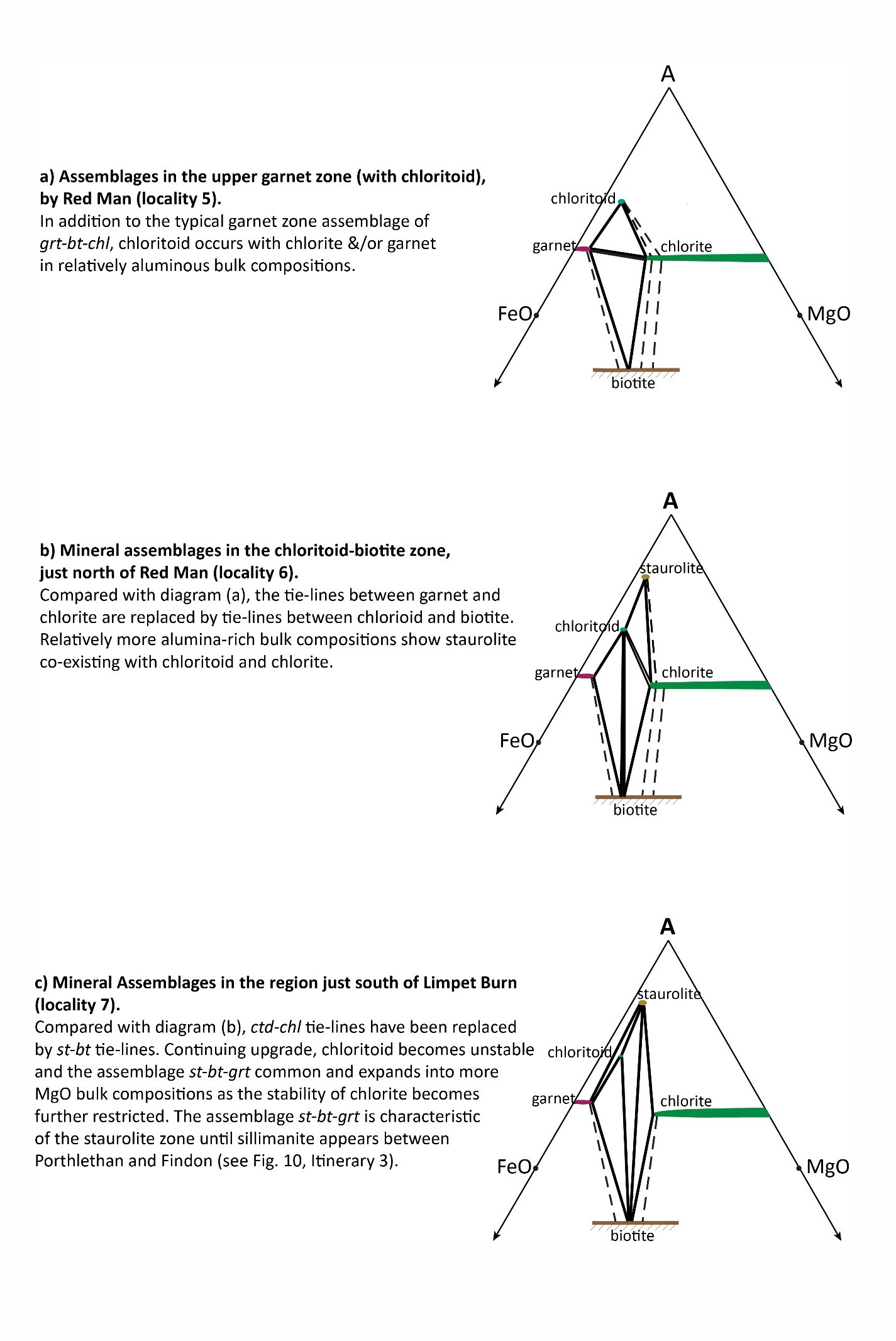

Mineral assemblages at the Red Man.

The Red Man–Limpet Burn area is notable for showing a significant number of pelitic and semi-pelitic beds in contrast to the grits and psammites which dominate the succession along Skatie Shore and Perthumie Bay.

On the Red Man promontory there are reasonably accessible exposures just above a grassy bank near the base of the ESE facing cliffs

The mineral assemblages on the promontory here and a little distance to the south are:

| Chloritoid-bearing assemblages | Biotite-bearing assemblages |

| Chloritoid-Chlorite (commonest) | Biotite-Garnet-Chlorite |

| Chloritoid-Garnet-Chlorite | Biotite-Chlorite |

| Chloritoid-Garnet |

In addition some schists contain garnet and chlorite without chloritoid or biotite (see

Folds and cleavages at Red Man.

On a ledge one third of the way up the promontory and accessible from the grassy slope on the south side, one can see a similar cleavage relationship as at locality 3 with S1, S3 and S4 cleavages. S1 and S3 have been folded by a large D4 fold, (wavelength 3 to 4 metres) which verges towards an antiform to the north, and to which the S4 cleavage is clearly axial planar. The relatively large scale of these D4 structures (related to the major Highland Border Downbend structure) at Red Man has produced a significant area of gently dipping beds in contrast to the steep dips generally encountered along Skatie Shore and Perthumie Bay.

About 40 m ENE from the promontory and a little below the high water mark, one can see open D4 folds with a moderately well-developed S4, and another cleavage which dips moderately to the SE. This latter cleavage maintains a constant dip and is not obviously folded by D4 — it belongs to a sporadically and generally weakly developed post-D4 deformation that is responsible for much of the gentle warping of bedding that can be seen along the section traversed so far.

1 The term 'isograd' is used here simply to refer to a line of first occurrence of a metamorphic index mineral as one heads upgrade.

Locality 6. [NO 8920 8880]

The bay between Red Man and Limpet Burn

About 30m north of the northern edge of the Red Man promontory at the normal high tide level some low exposures include a darkish grey-green pelitic unit

Also occurring in this region near Red Man and the staurolite-chlorite rich rock, are mineral assemblages containing the critical association of chloritoid+biotite together with either chlorite or garnet (see Figure 5b). Identifying such rocks in the field is difficult, because grain sizes are quite small and the rocks are rather altered (Chinner 1967) and the exposures rather dirty. The chloritoid+biotite assemblage has not been found on the Red Man promontory itself (locality 5). Comparing the chloritoid-biotite assemblages with the assemblages listed above for the promontory it is evident that garnet-chlorite tie-lines of the Red Man assemblages are replaced by chloritoid-biotite tie-lines to give the assemblages of

About 100m north of Red Man there are some small ridges that stick up through the shingle beach at the high tide mark. About 15 m north of these ridges just on the high tide mark there is a large antiformal, isoclinal fold of possible D3 age with a wavelength of 5 metres. It can be traced along the wave-cut platform since its axial trace is close to the strike of bedding. Associated with this fold, and others developed between here and Red Man, is an axial planar grain alignment cleavage with the same orientation and structural relationships as the S3 segregation cleavage seen at localities 3 and 5.

Locality 7. [NO 8930 8902]

On the north side of the bay and starting about 100 m south of the Limpet Burn there are abundant craggy exposures at high tide mark and above. The more pelitic units here are remarkable for their abundance of staurolite and biotite in small porphyroblasts (1 to 3 mm). The staurolite, which is exceptionally abundant, forms small stumpy prisms sometimes showing a yellow to brown colour; but often of a very pale colour due to replacement of staurolite by fine- grained white mica (Barrow's 'shimmer aggregate'). In the more southerly of these exposures garnet is hard to find, but it becomes more abundant as you approach Limpet Burn.

Rocks containing chloritoid may also be found around Limpet Bum, but are difficult to spot in the field. Some rocks showing layering on a scale of a few millimetres show interlayered staurolite- and chloritoid-bearing assemblages.

The assemblages seen around locality 7 are summarized in

Access to the A90 from the shore at Limpet Burn is difficult, and it is necessary to retrace your steps southwards to locality 2 and then ascend the path passing under the railway line and return to the layby from which you started out

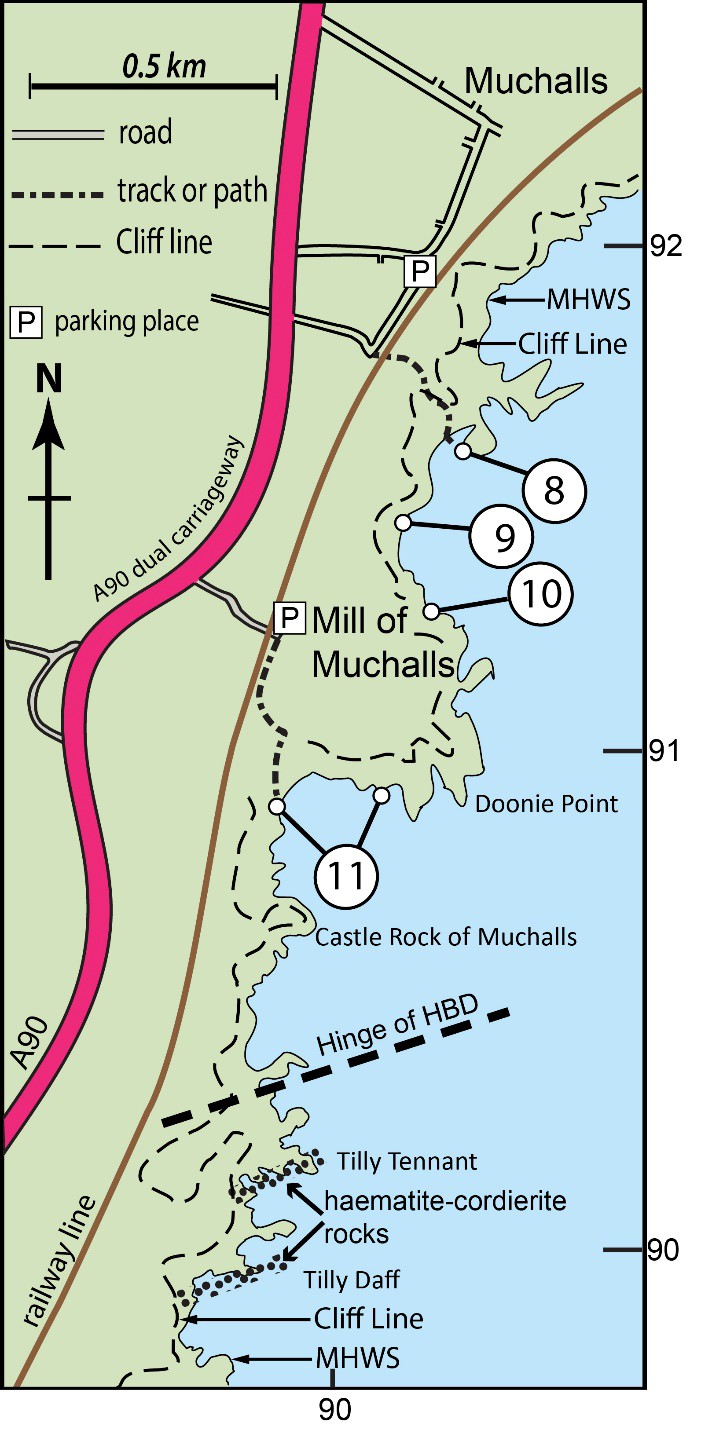

Itinerary 2. Muchalls area (fig. 7)

A quick tour of localities 8 and 9 may be done in 1.5 to 2.0 hours, but much more time should be allowed if you wish to examine the structures in any detail and do localities 10 and 11. Note that the path leading down to the shore at Muchalls is steep and slippery and not well maintained – proceed with caution! For locality 11 you need to drive from Muchalls village to the Mill of Muchalls

To reach locality 8, leave the Stonehaven-Aberdeen dual carriageway (A90) at

Locality 8. Ship Hole [NO 9028 9158]

On the southern face of the sea arch (Ship Hole) there are many D4 folds ranging in scale from a centimetre to several metres, with an overall vergence to the major Downbend antiformal axis (D4) in the south-east. Separated from the rocks of Ship Hole by a narrow gully a few metres wide is an elevated slab whose top surface is a bedding plane folded by a D4 fold pair verging on an antiform to the SE. The lithology is a psammite with a very strong NNW- trending D2 stretching lineation that lies on the bedding surface. This is a good place to see how folding affects the orientation of a lineation. Note also how the spacing of the S1 pressure solution cleavage, which parallels bedding to form the basic composite fabric of these rocks, is much more closely spaced than the same cleavage at Skatie Shore

Locality 9. [NO 9019 9144]

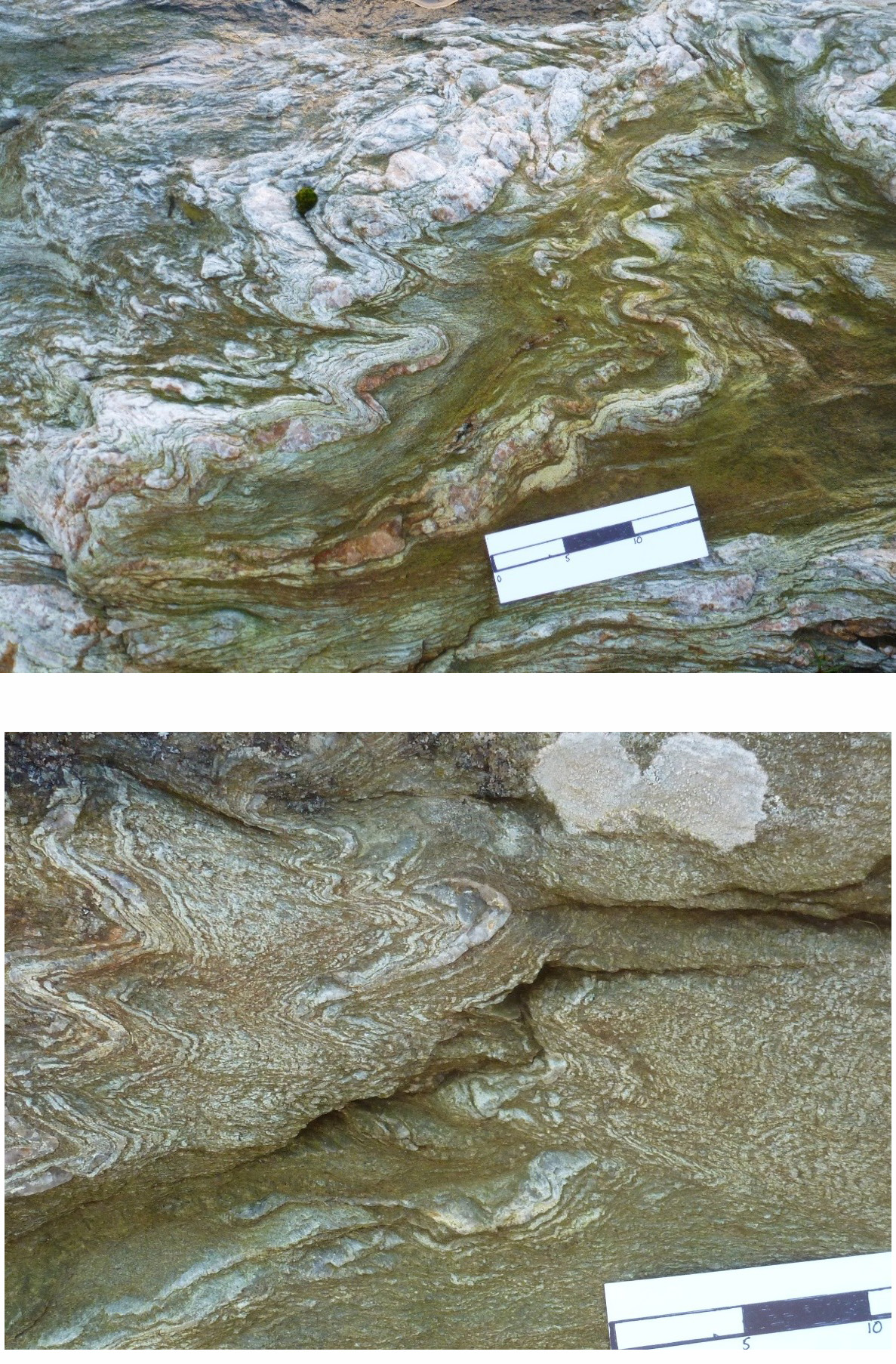

Near this locality there is a large stack detached from the cliff by about 15m. Along the high tide line four large blocks protrude from the shingle and are separated by three gullies (about 3 to 5m deep). The middle gully of the three provides probably the best exposure in which to see the complex range of D2 structures developed in the area. There are D2 folds with wavelengths from 1 cm to 1 m. The small folds form a variety of styles from stacked shear folds to buckle folds. There are no folds of other ages in the middle gully though the whole block is folded by a large somewhat open D4 fold.

Locality 10. (If time permits) [NO 9022 9126]

Southwards from locality 9 across a large pink felsite dyke, locality 10 lies in a small bay in which a stream pours forth from the mouth of a cave (the felsite has been extensively quarried above the cliff here, diverting the stream into the cave). Low tide is necessary before this locality can be reached. On the northern side of the bay just above the shingle it is possible to see examples of S3 folded by D4. In places here the lithology is of alternating bands of pelite and psammite about 10 cm thick. In several instances S4 is not only a good axial planar mica- schistosity but is complemented by thin (2 to 4 mm) spaced white mica seams — a spaced segregation cleavage. Locally an earlier muscovite segregation cleavage is folded by the D4 folds. This cleavage has the same geometrical relationships to bedding and S1 as the S3 cleavages seen at localities 1–6 and is thus correlated with them.

Locality 11. (If time permits) [NO 9012 9091]

Although the distance from locality 10 to Locality 11 is short, it is difficult get around Doonie Point, and it is best to drive from Muchalls to the Mill of Muchalls. Proceed from Muchalls back to the A90 dual carriageway and turn left. After a short distance take the small road to the left from the dual carriageway at

Near the end of this track exposures of rock commence at

Highland Border Downbend and haematite-cordierite schists.

To the south of Doonie Point, between Castle Rock of Muchalls (

Hinge of Highland Border Downbend between Castle Rock of Muchalls and Tilly Tennant.

The hinge is not a single large hinge but a whole series of small-moderate folds on scales up to several metres The folds are 'M' folds (with neutral vergence), with well-developed axial plane cleavage dipping about 45° NW. The position of the major axis is well constrained: north of the axis along the coast the dominant orientations of bedding and D1–D3 cleavage have a gentle southerly dip, whilst to the south the rocks have mainly steep dips, with minor D4 folds showing appropriate vergence.

Haematite-cordierite schists at Tilly Tennant and Tilly Daff.

Similar, distinctly unusual, rocks are exposed at both these localities, for the most part a little above H.W.M.. At first glance the rocks have something of the appearance of conglomerates in which matrix- supported pebbles and cobbles (hereafter referred to as 'cobbles') are embedded in a pelitic matrix. The 'cobbles' also appear to be pelitic in composition though with smoother weathered surfaces than the pelitic matrix. Examination of the matrix reveals essentially mica schists carrying abundant opaque grains (hematite and magnetite). Examination of the 'cobbles' shows that they carry an internal fabric which appears to be very similar to the composite bedding- cleavage structure of the matrix but rotated in the 'cobbles'. In some cases the bedding- cleavage structure, despite rotation, appears to pass continuously from the matrix through the 'cobbles'

Clearly these 'cobbles' are not what they superficially appear to be — they cannot be clasts of sedimentary origin, but are large crystals that have grown within the rock and appear to be porphyroblasts of metamorphic origin. The textural features are those frequently seen in fabric relationships of porphyroblasts and matrix, it is just that the scale is greater. It is suggested that the 'cobbles' are in fact altered porphyroblasts of cordierite. Cordierites of this size are not exceptional (Eskola 1914). Unfortunately, when examined in thin section the rocks are found to have undergone retrogression, and the porphyroblasts now consist of typical cordierite alteration products of fine-grained white mica and chlorite along with haematite. The unusual occurrence of cordierite here is attributed to two factors: (i) the hematite-mica schists provide unusual bulk rock compositions because their Fe is largely in the Fe3+ form and as a consequence they have a high Mg/(Mg + Fe2+) ratios (Chinner 1960; Harte 1975); (ii) the lower pressure of the Stonehaven section by comparison with the original type area of Barrow's Zones further west (Harte and Hudson 1979) would favour the occurrence of cordierite in rocks of high Mg/(Mg + Fe2+).

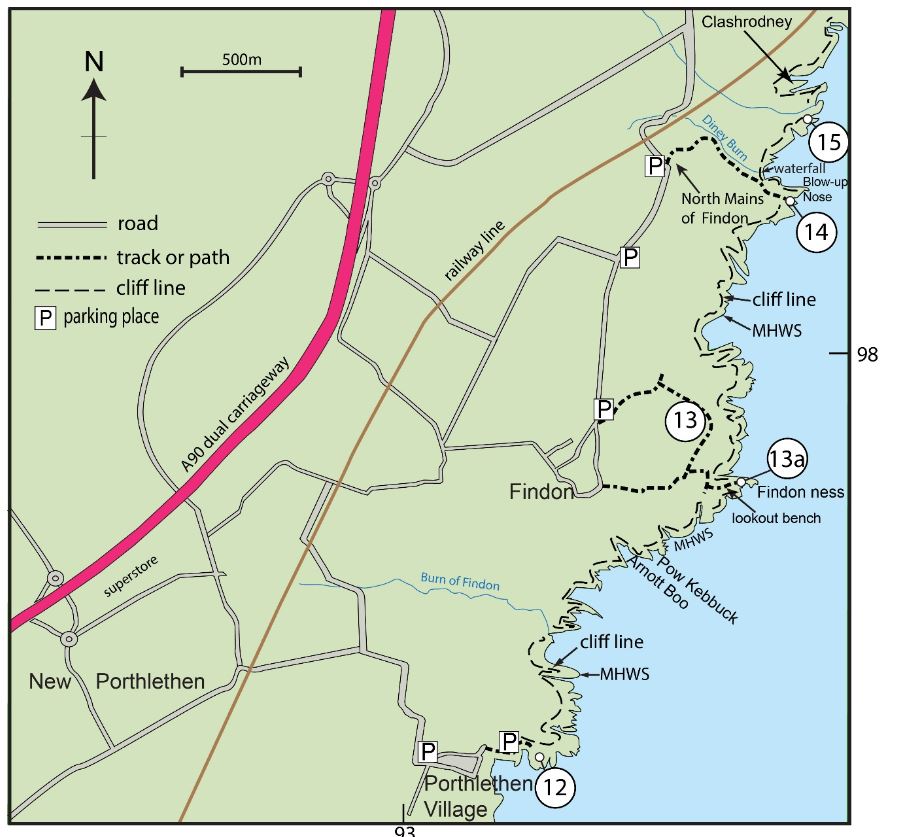

Itinerary 3. Portlethen to Clashrodney (Figure 10)

The first locality concerns the coast section by Portlethen village and requires about 1 hour. The objective is to examine D3 and D4 minor structures. In this region D3 minor structures are abundantly and widely developed, unlike in the areas further south. This is also an excellent locality for seeing high grade staurolite zone (staurolite-garnet-biotite) mineral assemblages and

From the dual carriageway take the road through the modern parts of Portlethen following the signs for Old Portlethen or Portlethen Village. Old Portlethen is perched close to the cliff tops, and as you enter the village, the road turns sharp left at the local public house – the Neuk. Immediately on the left, opposite the Neuk is a moderately large parking area

Locality 12. Portlethen [NO 9360 9625]

The extensive exposures here include some pelitic layers as well as abundant psammitic and semi-peltic rocks. Staurolite, typically in small yellow-brown prisms 2–3 mm long, is very abundant in some of these pelitic layers. The common assemblage is muscovite-bitotite-staurolite-garnet, though garnet is far less abundant than staurolite. The mineral assemblage is in fact very similar to that well seen in the highest grade rocks of locality 7 at Limpet Burn.

The rocks around this area also exhibit many fine examples of D3 minor folds, particularly on north facing joint surfaces

As seen at Muchalls (Locality 11), bedding surfaces in this area show a strong D2 stretching lineation in psammites trending NNW–SSE. There is also a second stretching lineation in psammites that trends about WNW–ESE, which overprints the D2 lineation and is folded by D4. Good examples of D3 folds and their relations to the other fold episodes and their foliations may also be seen on the south side of Portlethen Bay.

Locality 13 And 13a. Findon and Findon Ness [NO 942 978]

Allow 1 to 1.5 hours for this locality if you only wish to examine the minor structures, but two hours if you wish to see good exposures of sillimanite-bearing schists.

Park vehicles by the road junction

Many of the rocks here are psammitic and some are grits but there are occasional pelitic layers and these show the assemblage staurolite-biotite-garnet-sillimanite. Good examples of rocks with this assemblage are hard to find at locality 13, but particularly good exposures are seen at locality 13a (

In this region, sillimanite (fibrolite) first occurs proceeding upgrade near Arnot Boo and Pow Kebbuck about 0.7 km to the south of this locality

Locality 14. Blowup Nose [NO 9464 9867] and [NO 9473 9904]

Allow 1.0 to 1.5 hours for the Blowup Nose locality, and another hour if also wish to visit locality 15 (Clashrodney).

From Findon drive northwards towards the North Mains of Findon buildings

The plateau is easy to access and is covered in low-lying exposures of psammitic-pelitic schists and gneisses. The weathered surfaces of the more pelitic exposures show abundant sillimanite (fibrolite) in small (3–4 mm) upstanding knots or tufts. Garnet is rarely seen, usually embedded in fibrolite, but there is no staurolite, which has reacted out completely by this grade. Muscovite in 1 to 2mm bumps (+ fibrolite) may be seen on some surfaces and with the 'eye of faith' one may imagine some of them to represent replaced stumpy prisms of staurolite.

The pelites and psammites are locally intruded by sheets of granite (sensu lato) up to around 8m thick

Locality 15. Clashrodney [NO 9473 9904]

From the Diney Burn (above the waterfall!) you may proceed northeastwards behind the cliff line until you reach (after about 400m) another small stream running northeastwards towards the shoreline. Follow this stream to the top of the cliffs near Clashrodney

References

Atherton, M.P. & Brotherton, M.S. (1972). The composition of some kyanite-bearing regionally- metamorphosed rocks from the Dalradian. Scottish Journal of Geology 8, 203–213.

Barrow, G. (1893). On an intrusion of muscovite-biotite gneiss in the south-east Highlands of Scotland, and its accompanying metamorphism. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 49, 330–358.

Barrow, G. (1912). On the geology of Lower Deeside and the southern Highland Border. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 23, 274–290.

Booth, J.E. 1984. Structural, stratigraphic and metamorphic studies in the SE Dalradian Highlands. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Edinburgh.

Carmichael, D.M. 1969. On the mechanism of prograde reactions in quartz-bearing politic rocks. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 20, 244–267.

Chinner, G.A. (1960). Pelitic gneisses with varying ferrous/ferric ratios from Glen Clova, Angus, Scotland. Journal of Petrology 1, 178–217.

Chinner, G.A. (1966). The distribution of pressure and temperature during Dalradian metamorphism. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 122, 159–186.

Chinner, G.A. (1967). Chloritoid and the isochemical character of Barrow's Zones. Journal of Petrology 8, 268–282.

Droop, & Harte, B. (1993) The effect of Mn on the phase relations of medium grade pelites: constraints from natural assemblages on petrogenetic grid topology. Journal of Petrology 8, 1549–1578.

Eskola, P. (1914) On the petrology of the orijarvi region in southwestern Finland. Bulletin de la Commission Geologigue de Finlande, No. 40.

Foster, C.T. 1977. Mass transfer in sillimanite bearing pelitic schists near Rangeley, Maine. American Mineralogist 62, 727–746.

Gillen, C. & Trewin, N.H. (2015) Dunnottar to Stonehaven and the Highland Boundary Fault. Aberdeen Geological Society website.

Harte, B. & Hudson, N.F.C. (1979). Pelite facies series and the temperatures and pressures of Dalradian metamorphism in eastern Scotland. In: The Caledonides of the British Isles (Harris, A.L., Holland, C.H. & Leake, B.E., Eds.). Geological Society of London Special Publications 8, 323–337.

Harte, B. (2015). Barrow's Zones in Glen Esk, Angus, Scotland. Aberdeen Geological Society website.

Harte, B., Booth, J.E., Dempster, T.J., Fettes, D.J., Mendum, J.R. & Watts, D. (1984). Aspects of the post-depositional evolution of Dalradian and

Shackleton, R.M. (1957). Downward-facing structures of the Highland Border. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 113, 361–392.

Stephenson, D., Mendum, J.R., Fettes, D.J. and Leslie, A.G. 2013. The Dalradian Rocks of Scotland: an introduction. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, 124, 3–82.

Tanner, P.W.G., Thomas, C.W., Harris, A.L., Gould, D., Harte, B., Treagus J.E. & Stephenson, D. (2013). The Dalradian rocks of the Highland Border region of Scotland. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 124, 215–262.