Show interactive timeline

Barrow's Zones in Glen Esk, Angus, Scotland

Ben Harte

An illustrated PDF download is available from the Aberdeen Geological Society website

Purpose

To examine the sequence of regional metamorphic zones developed in Dalradian rocks within the type area of Barrow (1893, 1912); and to note some of the lithological and structural features seen in the

Access

The field itineraries are in Glen Esk and commence at the foot of the Glen where the B966 crosses the North Esk at Gannochy

In this itinerary various options are indicated according to the means of transportation and time available. The Glen roads are not well suited to large buses or motor coaches, but it is possible to use a small bus for 20 to 25 persons. Bus parties should walk (about 5 km) all the way from the

The time required for examination of the rocks from the

The area is covered by Ordnance Survey 1:50,000 sheet 44, and 1:25,000 sheets 389 and 395; it is within British Geological Survey sheet 66W.

There are public conveniences beside the recreation area on the northern margin of Edzell. There are also hotels and cafes in Edzell; and there is also a cafe in Glen Esk at the Retreat museum near Tarfside

Introduction

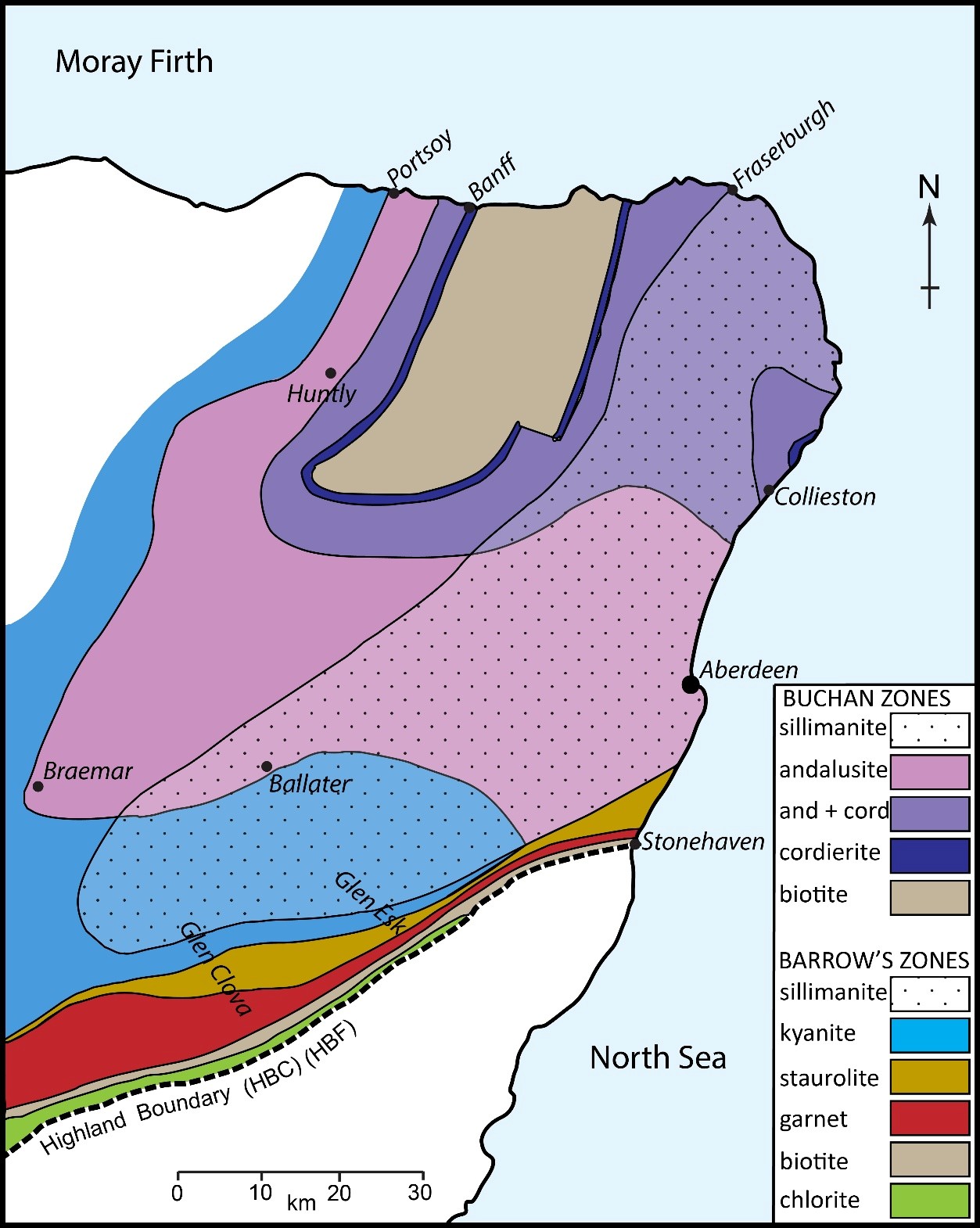

This excursion to Glen Esk provides localities for seeing each of Barrow's zones: chlorite, biotite, garnet, staurolite, kyanite, sillimanite (Barrow 1893, 1912; Tilley 1925). Barrow's Zones lie in the southern part of the region of complex metamorphism found in the Dalradian rocks of the Eastern Highlands of Scotland

Studies in this region of the Eastern Highlands played a critical role in the development of the concepts of regional metamorphism (Horne, 1884), and the recognition of metamorphic zones (Barrow, op. cit.). For an overview of 'regional' metamorphism in the whole of the region of

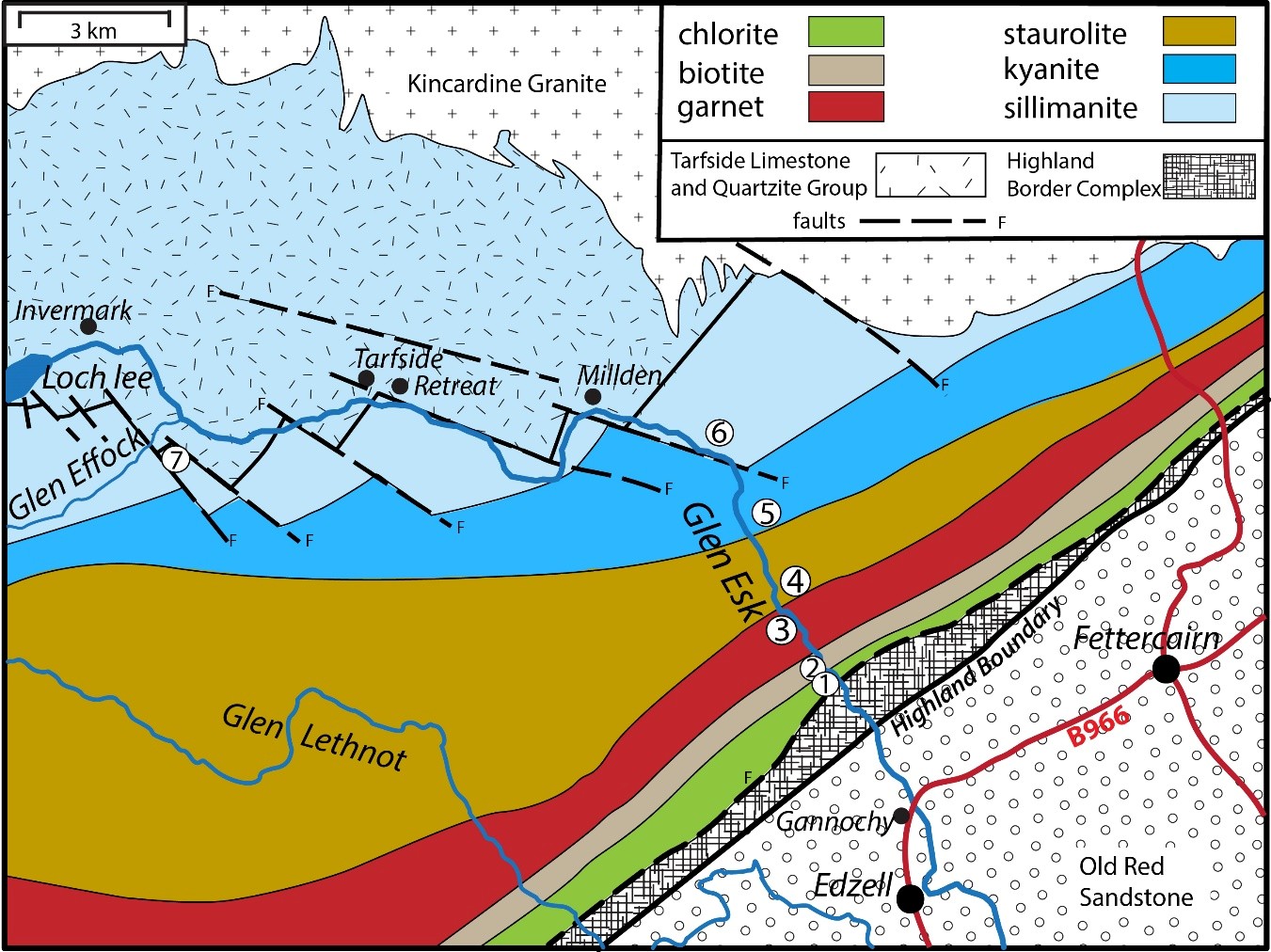

The localities described in this guide for the chlorite, biotite and garnet zones lie within an extensive set of exposures on the banks of the river North Esk, extending from the Lower Old Red Sandstone in the south, across the

With the exception of the

Notes on major rock relationships

(1) Barrow's Zones

Barrow's original delineation of his zones was centred on Glen Clova and Glen Esk (Barrow, 1893) and was subsequently extended to the coast at Stonehaven (Barrow 1898, 1912). Barrow's mapping of the metamorphic zones has only been marginally changed by later workers (e.g. Harte 1966; Chinner and Heseltine 1979). He referred to the region as one of "regional crystalline metamorphism" (1912, p.3) but given the presence of mineral zones and increasing mineral grain sizes he drew an analogy with “aureoles of thermo-metamorphism” around granite bodies. Barrow clearly recognized that his zones preceded the intrusion of large coherent "Newer Granites" in the Scottish Highlands and instead related them to the presence of "Older Granites"1 (1 Barrow had no radiometric data to provide estimates of absolute age, and thus made relative estimates by comparison with other geological events in the Scottish Highlands. The Newer Granites he referred to in the Highlands have now yielded radiometric dates of

"…..reasonable to attribute both the minerals and the crystallization to the thermometamorphism of the intrusion." (Barrow 1893, page 337).

Tilley (1925) extended Barrow's mineral zone mapping to the west across the Dalradian of the central and south-western Scottish Highlands. In this he introduced the term 'chlorite zone' for the combined zones of 'clastic mica' and 'digested clastic mica' previously recognised by Barrow. The area mapped by Tilley (1925, Plate IX) was formed by the newly-defined chlorite zone together with the biotite and garnet zones; though he was aware (Tilley, 1925, in 'Discussion', p. 112) of an area of staurolite and kyanite-bearing rocks to the north of the area covered by his Plate IX. Throughout the whole of the central and south-west Highlands, Tilley noted the rarity of 'Older Granites' and thought it more likely that they were a product rather than a cause of metamorphism. Tilley thought it reasonable to suggest:

"…..that the metamorphism of this region was essentially acquired at a stage in Dalradian history when the disposition of the zones was in approximate accord with the depth of burial of the sediments…." (Tilley 1925, p. 109).

Barrow's and Tilley's opinions largely rested on the spatial distribution of the metamorphic zones, and other essential field relationships, and these matters have continued to contribute to debates on the origin of the metamorphic zones. In addition, knowledge relevant to the origin of the zones has grown extensively in the following fields:

- the detailed history of deformation and structure development, accompanied by petrographic evidence of phases of mineral growth in relation to detailed structural history;

- detailed knowledge of mineral compositions and phase equilibria;

- the development of models of heating and heat transfer in the lithosphere;

- the use of radiometric dating to provide evidence of the ages of igneous intrusions, migmatites and metamorphic mineral growth.

With respect to structural history and the petrographic textures of mineral growth, four major phases of deformation (D1, D2, D3, D4) have been widely recognized; with D1-D2 associated with nappe development (especially the Tay Nappe), and D4 associated with major folding particularly represented by the Highland Border Downbend structure (Shackleton, 1958; Harte et al. 1984; Stephenson et al., 2013a; Tanner et al., 2013). The growth of metamorphic index minerals (garnet, staurolite, kyanite, sillimanite) has been found to be predominantly associated with the period between D2 and D3 and overlapping D3, but with some relatively late growth of sillimanite probably following D3 (Chinner, 1961; Harte & Johnson, 1969; Harte & Hudson, 1979; McLellan, 1985; Robertson, 1991, 1994). With regard to the matrix minerals (largely quartz, muscovite and biotite), Harte & Johnson (1969) believed they had undergone major recrystallization and grain coarsening in association with the D3 phase of deformation.

Chinner (1966) led the way with a new approach to questions considering temperature distribution, depth and structural evolution, by using the variable P-T constraints of mineral reactions at the boundaries of metamorphic zones, to map relative temperatures and pressures and their pattern of variation with respect to one another. Chinner suggested that synmetamorphic folding had given rise to a thermal anticline near centre of the combined Barrovian and Buchan metamorphic zones. Harte & Hudson (1979) followed Chinner's approach of attempting to delineate isotherms and isobars across the Eastern Highlands, and determined the actual temperatures and pressures involved by using a petrogenetic grid in which the isograd reactions were defined. They concluded that the major pattern of temperature and pressure distribution favoured the formation of the metamorphic zones, the migmatites and the 'older granite' bodies as a result of extensive regional magma intrusion in the deep crust. Overall, Harte and Hudson (1979) estimated that the garnet to sillimanite zones had formed at temperatures of ca 520 to 680 °C, and pressures of near 6 kbar (but lower pressures on the Stonehaven coast section than in Glens Clova and Esk). More recent detailed estimates on specific zones and mineral assemblages have confirmed a similar range of temperatures and pressures (e.g. Dempster 1985; McLellan 1985; Baxter et al. 2002; Viete et al. 2011a; Vorhies & Ague 2011).

In considering the general pattern of arrangement of the metamorphic zones in

Tilley's alternative model of the metamorphic zones as basically reflecting the increase of temperature with depth within the metamorphic pile was re-examined for the garnet zone in the western central Highlands by Richardson and Powell (1976). They concluded that garnet- zone temperatures of ca. 535 °C could be supported by radioactive heat production within a thick Dalradian metasedimentary pile plus an underlying thickness of Moinian metasediments, and that there was no need to invoke the presence of underlying magmatic intrusions. Richardson & Powell (1976) also noted the transient nature of their thermal model, because the thickened Dalradian pile would take time to heat itself up and after thickening would be thinned by erosion. A wide range of dynamic models of this type were further developed by England & Richardson (1977) and England & Thomson (1984) showing that a thickened sedimentary pile might undergo thickening, heating and erosion and reach temperatures appropriate for the highest grade Barrovian metamorphic rocks. However, the timescales for development of high grade rocks in this manner was typically shown to take tens of millions of years, and the time at which peak metamorphic temperatures were reached in each metamorphic zone might also differ by tens of millions of years.

Returning to consideration of the high-grade metamorphic zones of Barrow's type area and the Eastern Highlands in general, the thermal models of England and co-workers provide a framework for comparison with the results of radiometric dating. In the Buchan region, Fettes (1970) demonstrated that there was a continuity in the development of minerals found in the Buchan regional andalusite zone and in the aureole of major gabbro bodies; thus the dating of these bodies at close to

Although there now appears to be a broad consensus in favour of regional magmatic intrusions as the cause of heating in the Barrovian type area, some differences of opinion remain. Viete et al. (2013) believe all the heat input came from episodic intrusions (perhaps accompanied by episodes of fluid flow). Vorhies & Ague (2011) believe magmatic heat was instrumental in getting the higher grade rocks to high temperatures in a short time; but in contrast to Viete et al., they suggest the magmatic heat transport operated in addition to thermal input from a thickened pile of radiogenic metasediments as in the models of England & Thompson (1984). Vorhies & Ague (2011) emphasise the magmatic input of heat for the Eastern Highlands, but not for the lower grade central and south-western Highlands. This contrast has features reminiscent of the original differences of opinion of Barrow (1893, 1912) and Tilley (1925) for the respective areas that they mapped.

(2) Highland Border Complex

The rocks found adjacent to the southern margin of the Dalradian metamorphic rocks, at the Highland Boundary, have also prompted much debate. In Glen Esk

- The Jasper and Greenstone Series — formed largely of altered fine grained basic igneous rocks (greenstones), cherts and some shales in a low grade of metamorphism. Pillow structures occur in some metabasic rocks. These rocks are widely believed to be related to metabasalts and serpentinites occurring at several places along the Highland Border (including nearby at Garron Point, Stonehaven). Many workers have accepted the suggestion that at least some of these rocks are of ophiolitic origin; but there have been different opinions about the extent of their tectonic separation in time and place from the Dalradian.

- The Margie Series — this consists of weakly metamorphosed pebbly sandstones ('grits'), shales and limestones. A Lower

Ordovician age has recently been demonstrated from conodont evidence in the limestone (Ethington 2008), and this is consistent with the fossil evidence from other low-grade metasediments in theHighland Border Complex near Aberfoyle (Tanner and Sutherland 2007).

Dips of bedding and cleavage are commonly steep

A continuity in structural history between the Margie Series and the Dalradian rocks to the north was emphasised by Johnson and Harris (1967). However, Henderson and Robertson (1982) and Harte et al. (1984) felt that this evidence was distinctly tenuous because some obviously different geological terrains can show similar structural histories. Henderson and Robertson (1982) suggested that the whole

The debate has continued more recently. Tanner, Stephenson and others (e.g. Tanner and Sutherland 2007; Tanner et al. 2013; Stephenson et al. 2013b) have argued that the whole HBC in the River North Esk belongs to the

In the River North Esk, the southern margin of the

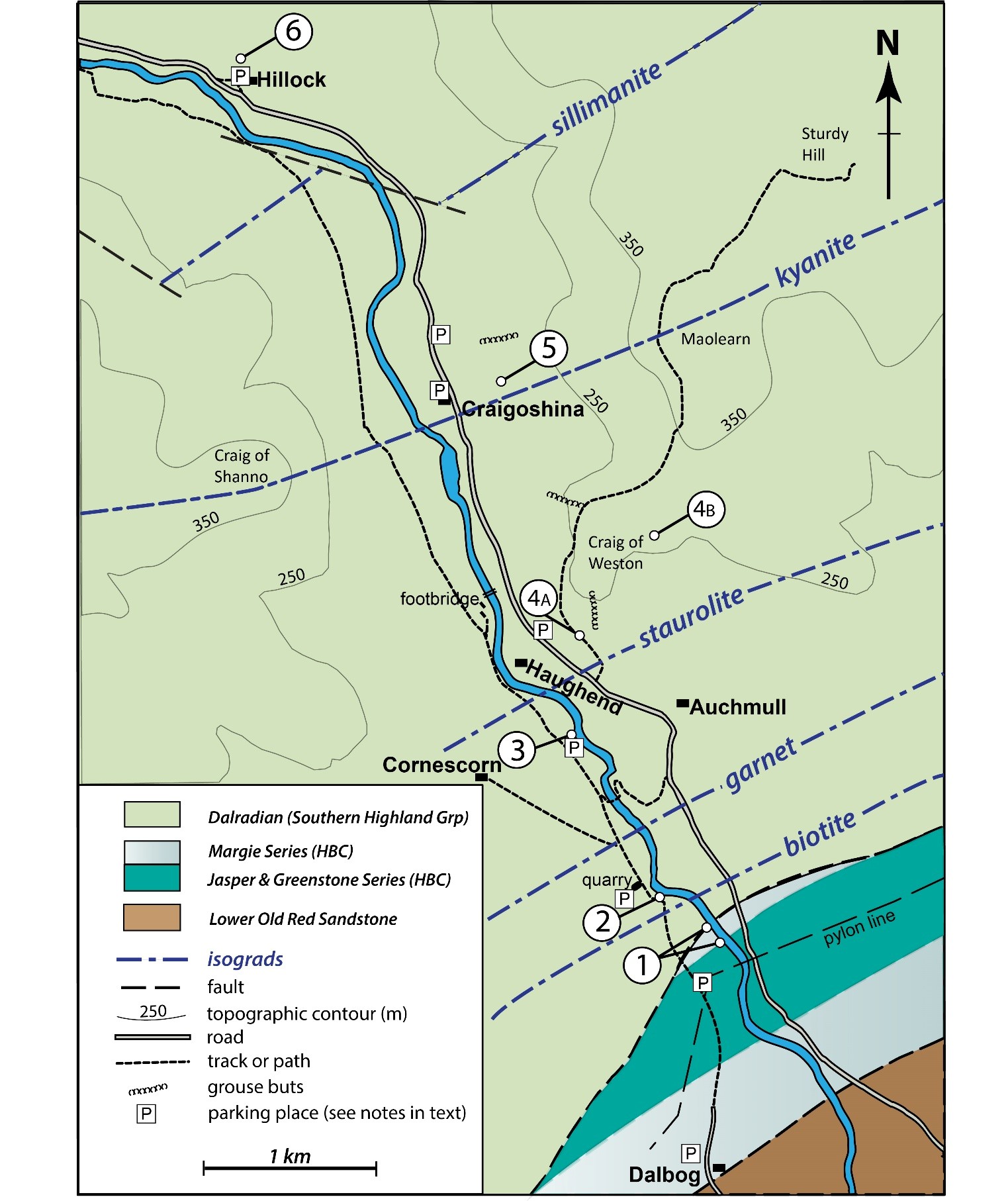

Traverse from the Chlorite Zone to the Staurolite Zone

This section of the excursion, covering the chlorite to staurolite zones (localities 1 to 4), is described in a single section because it is possible to walk through the whole of this sequence without using a vehicle; the river is crossed by a footbridge between localities 3 and 4. This walking itinerary is particularly useful for coach parties, since some roads/tracks are very unsuitable for motor coaches (see below). However, notes are given on parking places for small vehicles so that people driving themselves may easily do localities 1 to 3 on the west side of the Glen, before driving to the east side of the Glen to locality 4.

Proceed along the (B966) to near Gannochy where the B966 bridges the River North Esk about 1.6 km north of Edzell

After leaving the B966 follow the narrow road north-west for 2 km until reaching the road and track junction at

From the road junction by Dalbog pedestrians and small vehicles head on north passing the large cattle shed on the left until reaching the point

Locality 1. Highland Border Complex and Dalradian chlorite zone

Looking from the track near the pylon line

Leaving the parking area beside the track and pylon line

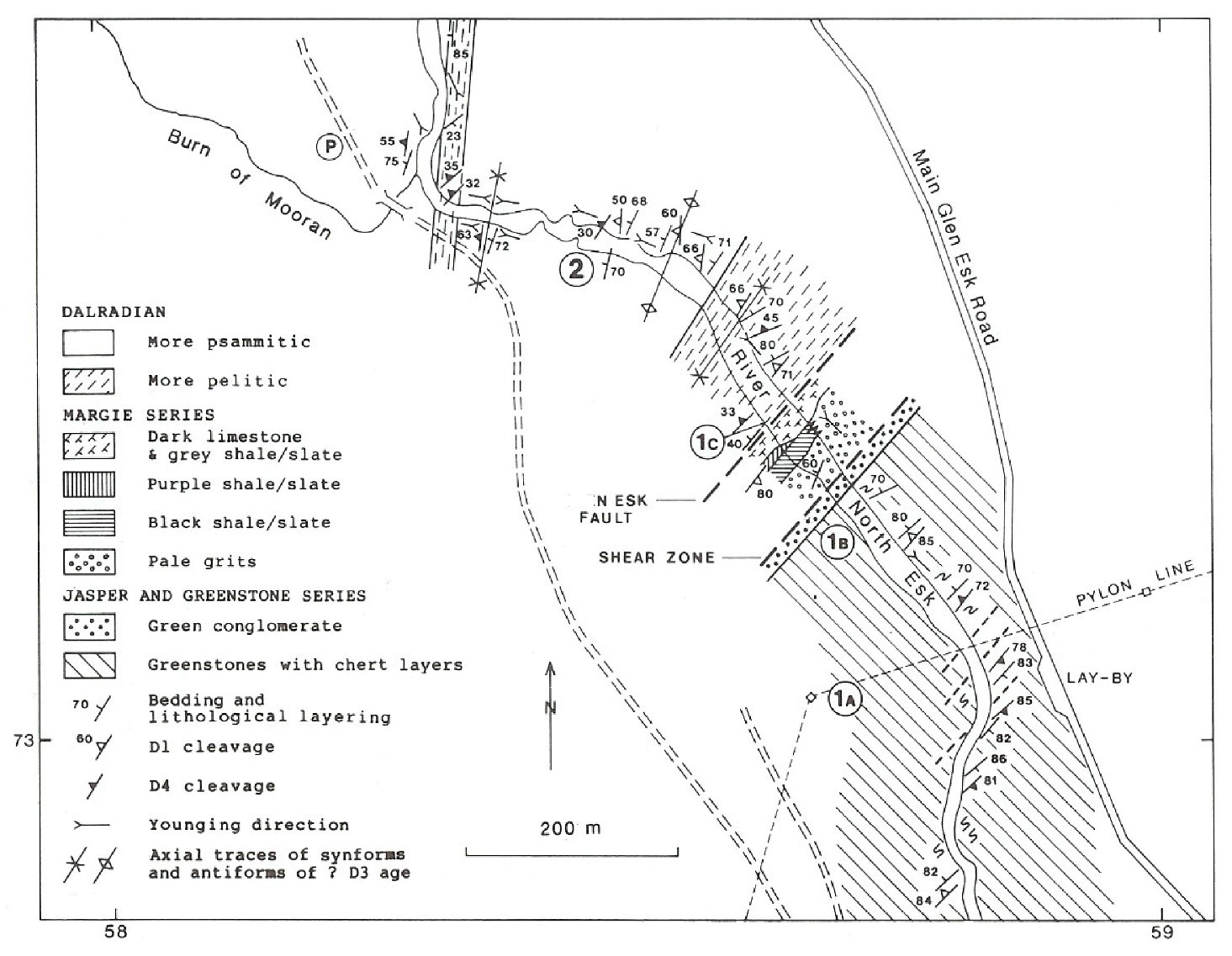

Locality 1A [NO 587 731]

Visitors may spend a little time around here, on the south side of the pylon line

Locality 1B [NO 5870 7324]

This locality

At the northern end of the prominent crags a conglomerate occurs (the 'Green conglomerate') consisting of greenstone pebbles and cobbles in a fine-grained schistose green matrix which largely resembles the greenstones mineralogically, but is occasionally more pelitic. Although most of the clasts in the conglomerate are of fine-grained rocks, some occur which may be derived from dolerite or gabbro. There are also rare jasper pebbles. A few metres to the SE the more usual massive greenstones are encountered.

When the river water is low, almost continuous exposures show that, to the NW, the conglomerate changes over a few metres from conglomerate with few relict clasts in the schistose matrix, through green schist without clasts, to paler highly schistose rocks and eventually to brown-weathering cleaved dominantly psammitic rocks with small pebbles ('grits' in local terminology). The last of these is definitely a Margie Series lithology.

The Green conglomerate was considered by Barrow (1912) to be separated from the main Jasper and Greenstone Series outcrop to the south by a minor thrust. Other workers (Pringle 1941; Henderson and Robertson 1982) have also placed a fault or thrust in this position, though Pringle emphasised the lithological similarities of the conglomerate and the greenstones. With respect to the Margie Series, Barrow (1912) considered the Green conglomerate as forming its base with a passage upwards into the main Margie rocks. However, Pringle (1941) noted that, at exceptionally low water, exposures (on the opposite side of the river) suggested that a fault or shear zone separated the greenish shaly/schistose rocks from the paler (brown-weathering) shaly/schistose rocks and grits.

Localities 1B to 1C [NO 587 733] to [NO 586 734]

The Margie Series outcrops in the interval between localities 1B and 1C; but in this interval rock exposures are infrequent by contrast to the craggy exposure which border the river both upstream and downstream. There is usually patchy exposure along the water's edge and if the water is particularly low, much rock may be seen within the river.

For about 50 m upstream of the Green conglomerate, the exposures are mainly of the pale grit. Locally, these grits show brecciation and at one point a very dark brecciated band is seen. For the next 50 metres after the pale gritty psammites, black and then purple shales/slates dominate the exposure at the water's edge on the west bank

The whole exposure of the Margie Series is very complex. Although similar rock types are seen on both banks their proportions on the two banks are very different

Locality 1c [NO 586 734]

At this point an upstanding craggy exposure occurs at the water's edge and, immediately behind it, crags around 4 m high commence and form the western margin of the river upstream.

The exposures consist of compositionally layered, grey-green, pelitic and more psammitic, chlorite-muscovite schists or phyllites

The layering within the rocks at locality 1C is bedding and this may be demonstrated where occasional grit beds containing clasts of quartz and feldspar occur. Such evidence is more easily seen at locality 2. A cleavage (schistosity) occurs sub-parallel to the bedding, which dips upstream at moderate angles. This dip is much shallower than that generally seen in the section. Also dipping upstream, but at a shallower angle than the bedding, a second cleavage may be seen, particularly in pelitic beds.

These two cleavages belong to the two dominant deformation episodes to have affected the Dalradian rocks adjacent to the Highland Boundary. The first (close to bedding) cleavage is associated with D1, the early nappe-forming episode. The second cleavage is associated with D4, the major Highland Border Downbend structure. D2 and D3 structures of easily identifiable style are not seen in the Dalradian here, and only become common further away from the Highland Boundary, as elsewhere in the Dalradian (e.g. Harte et al. 1984; Harris et al. 1976; Tanner et al. 2013).

Locality 2. Biotite zone [NO 5838 7348]

From locality 1C retreat a short distance back towards the Margie exposures and scramble up the bank forming the western side of the river gorge. Proceed NW, keeping a little above the river gorge until you are within a few metres of reaching the vehicle track

The rocks here generally dip steeply NW

The lithology here is similar to that at locality 1C but includes distinct beds of pebbly meta-sandstones ('grits') up to about 1 m thick

Locality 3. Garnet zone. [NO 578 744]

From locality 2 climb back up the bank to the road/track and follow it NW across the Burn of Mooran and past the small quarry

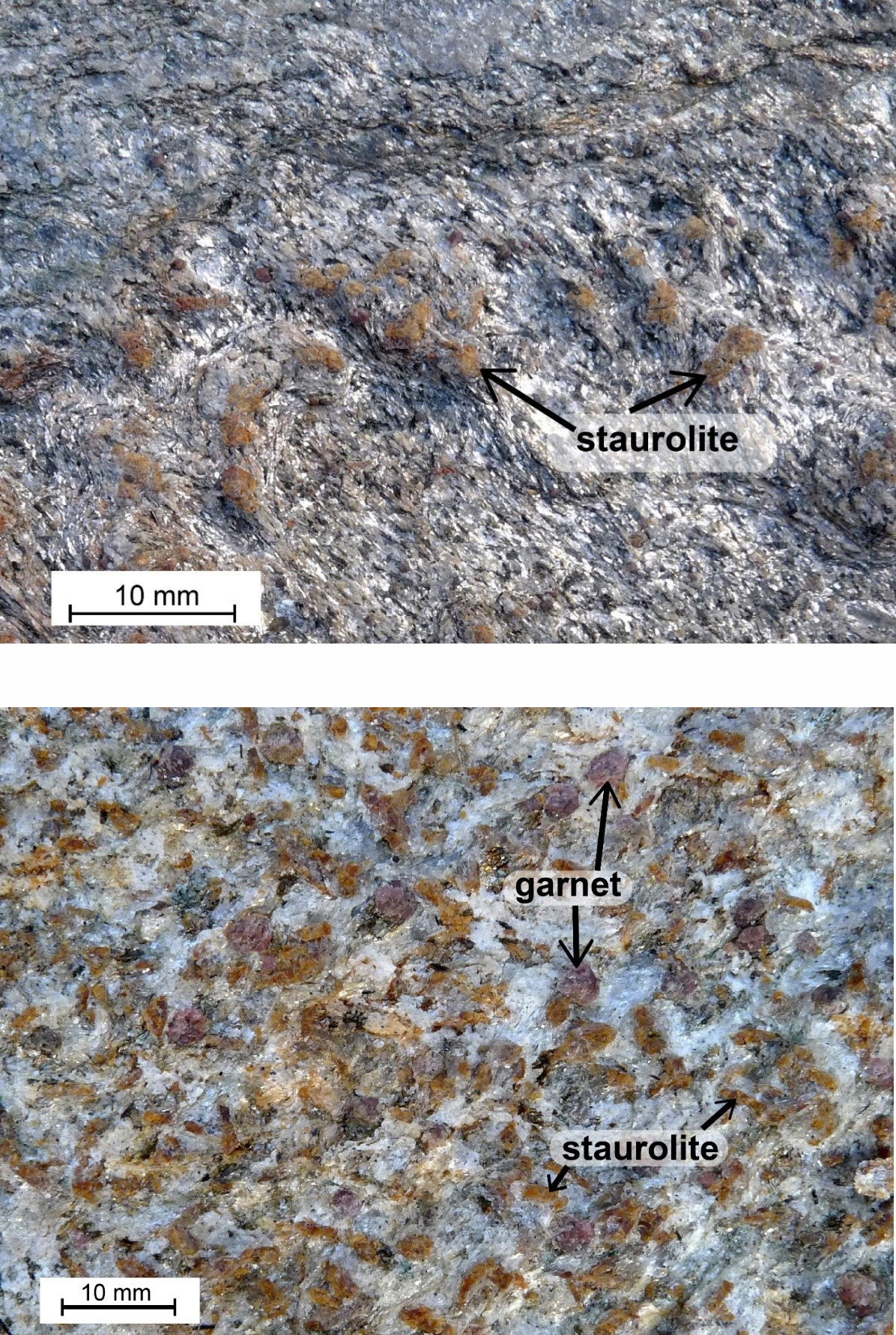

The lithology is of the bedded pelitic and more psammitic units similar to those seen downstream. The grain-size is a little coarser with a schistosity defined by chlorite and muscovite. Biotite forms small porphyroblasts, generally up to about 3 mm. Garnet is sporadically abundant in porphyroblasts of 2–5 mm; it is particularly well seen on the SE side of low exposures which protrude into the river. Similar rocks may be seen under overhanging trees along the river's edge for a short distance to the SE, but further away the lithology includes much coarse 'grit', and garnet is hard to find.

Locality 4. Staurolite zone

Looking north obliquely across the river from locality 3, the major spur of the Craig of Weston faces the observer and the staurolite zone rocks of locality 4 ('A' and 'B') lie on and adjacent to this spur. The route to these localities from locality 3 depends on the transport arrangements of the field party, but in all cases the ascent of the Craig of Weston may be conveniently made from a layby at

Field Parties on foot from Dalbog should return to the track (150 m west of locality 3), and follow it NW for about 0.7 km. At this point a track forks to the right and leads down into a field containing barrack-like huts. Behind the huts the river is crossed by a footbridge from which a path leads to the main Glen Esk road; and the layby at

Field parties driving themselves should return to their vehicles and drive back to Gannochy and the B966, and then take the road signposted to Tarfside and Invermark up the east side of the valley to reach the layby at

Locality 4A [NO 578 753]

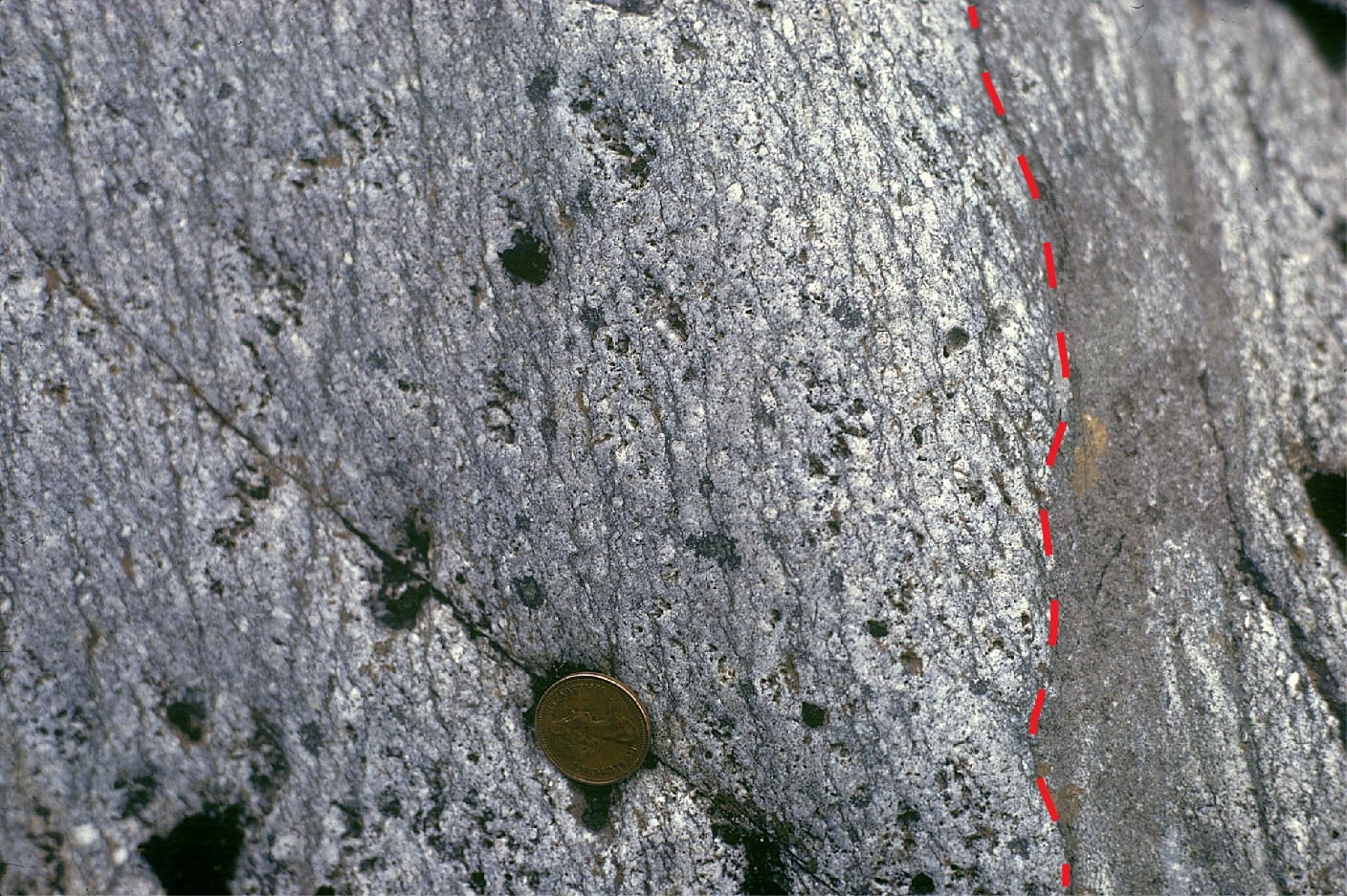

From the layby at

The staurolite usually forms upstanding stumpy prisms 2–3 mm long

At this point the field party may return to their vehicles at the

Locality 4B [NO 583 756]

This location is about 400 m NE of the knoll with isolated trees described above, and on the south-eastern side of the ridge heading upwards to the top of Maolearn hill

4A. Again, they are not abundant because much of the rock is semi-pelitic to psammitic and they should be searched for at the SE margin of the area of exposure. Please do not hammer the in situ rocks. Loose material showing the typical assemblage (garnet-staurolite-biotite-muscovite schist) may be found just beyond the SE margin of the exposure adjacent to a shallow gully (probably a small glacial overflow channel).

The rocks at 4B show a composite foliation dipping moderately steeply to the ESE. This foliation includes cleavage structures and compositional layering; the latter is indicated to be bedding by the occurrence of psammitic layers which appear to be the higher grade equivalents of some of the finer-grained grits seen at the lower grade. The cleavages forming part of the composite foliation include schistosity in pelitic layers, which passes into a spaced cleavage in semi-pelitic to psammitic layers. In places the spaced cleavage reveals small shear zones typical of Dalradian D2 deformation structures (Harris et al.1976; Harte et al. 1984). Relicts of D1 cleavage may be seen traversing some of the lithons (commonly 0.5–2.0 cm thick) between the attenuated D2 shear zones, thus proving the composite nature of the dominant foliation structure. A ribbing or rodding lineation largely lying in the foliation plane may be seen on some quartz veins and psammitic surfaces. This is probably also of D2 age and in Glen Esk is generally much easier to find than separate evidence of both D1 and D2 structures in the composite foliation.

Obvious tight minor folds of amplitudes from a few centimetres to a few metres also occur at locality 4B. At the hinges of these folds pelitic layers often show an axial planar cleavage which passes into parallelism with the composite foliation in fold limbs. These folds also fold the probable D2 lineation and are thus considered to be D3 in age. It is however extremely difficult to find a clear example of obviously composite D1 + D2 fabric being folded around the hinges of these folds (such evidence is generally much harder to find in Glen Esk than on the Stonehaven coast section - see the excursion guide to the Stonehaven coast section (Harte et al. 2015). Cleavage associated with D4 is not so well developed here as in the river (localities 1C and 2), but crenulations of schistosity with axial planes dipping northwest are almost certainly of D4 age. Some other crenulations may be seen. Altogether, there is evidence at locality 4B of the four main deformation events seen in much of Glen Esk; these are the D1 to D4 of Harte and Johnson (1969), which are in fact common to much of the Dalradian of the Southern Highlands (Harris et al. 1976; Harte et al. 1984).

Between the garnet-zone exposure (Locality 3) and the staurolite-zone (Locality 4) the rocks have changed quite significantly in other characters besides the increase of grade marked by the staurolite-garnet-biotite assemblage. The effects of D2 and D3 deformation have become manifest, whilst the essential pelitic to psammitic characteristics of the rocks have remained much the same. It is a great pity that the garnet-staurolite zone transition is generally so badly exposed in Barrow's zones. Higher up Glen Esk and in adjacent Glen Lethnot, it has been shown that the main growth of garnet, staurolite and kyanite porphyroblasts is prior to and partly synchronous with D3 (Harte and Johnson 1969; Dempster 1985); whilst much of the coarsening of the rock matrix seems to be associated with the D3 deformation, whose axial plane cleavage becomes part of the composite foliation on the limbs of D3 folds.

After examining the 4B exposures, parties may descend Craig of Weston to recover their vehicles at the

Locality 5. Kyanite–bearing rocks [NO 575 766]

Locality 5 is directly uphill from Craigoshina cottage which is on the roadside at

To gain access to the area with good exposures of kyanite-bearing rocks go to the fence immediately across the road from the northern end of the Craigoshina buildings. Immediately to the left of a stout corner fence post, examination of the fence shows that the wires two to three feet above ground level are arranged so that they may be flapped upwards, making a space where you may bend and get through without damaging the fence. Please take care, and remember to lower the wires back in place after passing through.

Proceed directly up the hillside away from the fence, passing through a wooded zone before reaching an area with rock exposures and much loose rock, 300–400 m up the hillside from Craigoshina

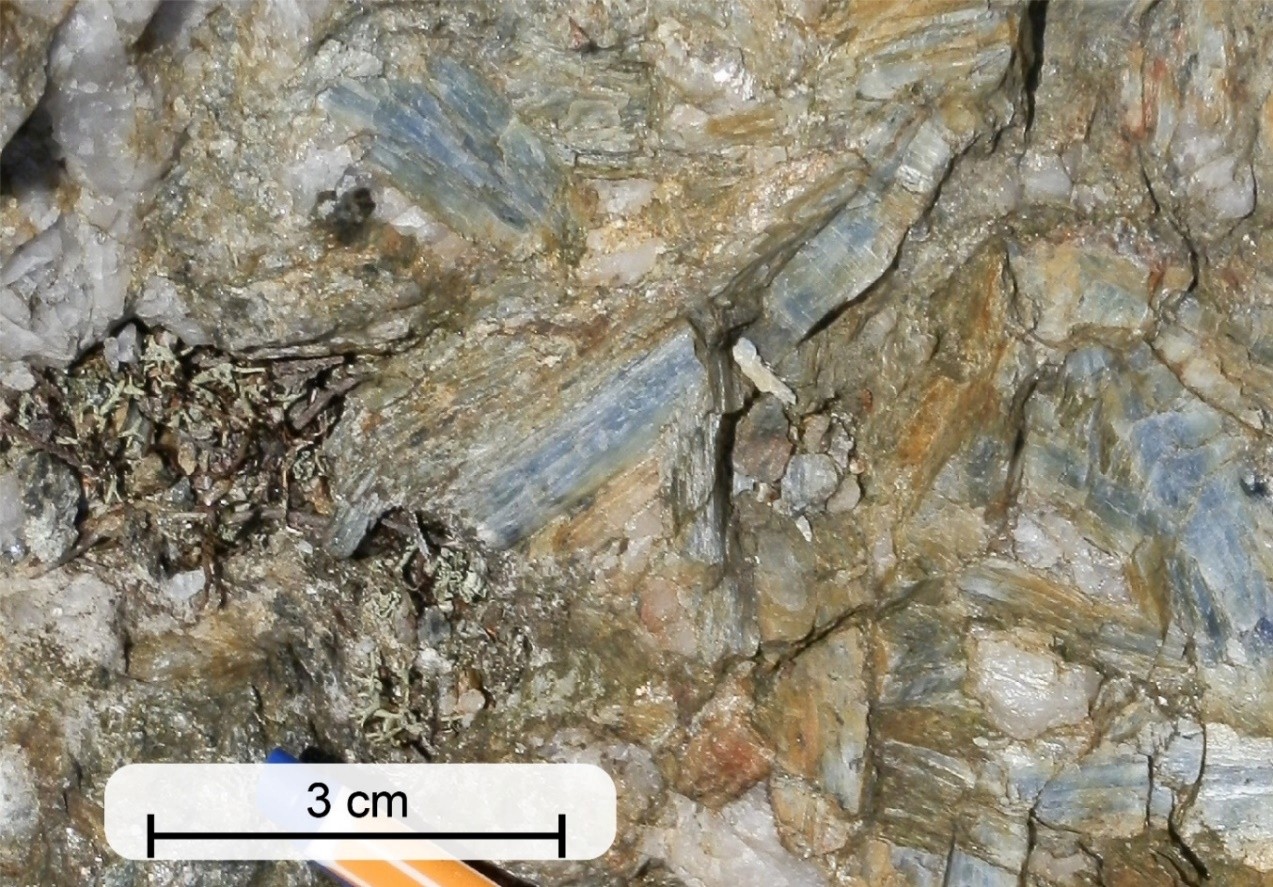

In the kyanite-haematite schists, the kyanite prisms may be 0.5 to 3.0 cm long. Unfortunately these prisms do not have the usual attractive streaky blue-white colouring, because they are often rather altered and full of small haematite inclusions; thus on weathered surfaces the kyanites form upstanding prisms with a dark silvery-grey appearance similar to that of the body of the schists. Barrow (1893) referred to such kyanite as “black-leaded”. Sometimes, due to alteration to fine-grained mica, the kyanite acquires a waxy appearance. Occasional dark seams and patches may be seen within the schists and these represent concentrations of haematite. Some haematite-bearing schists with lower ferric:ferrous ratios show staurolite in stumpy prisms 2–4 mm long.

Kyanite-rich rocks are particularly well seen in the uppermost part of the extensive exposures. In addition spectacular quartz veins with abundant kyanite may be found

Please do not hammer attractive exposures of the kyanite-quartz veins; it is possible to obtain some specimens from loose-lying material.

In Glen Lethnot, which is the next glen to the SW of Glen Esk

Sillimanite Zone localities

Two options are described below for viewing sillimanite zone rocks. The first option (locality 6) is a short drive up the Glen of about 3km from Craigoshina

Locality 6. Sillimanite zone by Hillock [NO 559 784]

From the vicinity of Craigoshina, drive north up Glen Esk for approximately 3 km to a road bend at

To reach the exposures on the nearby hillside, walk along the western side of the most westerly farm building and then across a field and a belt of ferns with the remains of sheep pens on the right. In the group of rock exposures facing you there are again many psammitic and pelitic rocks. Sillimanite-bearing pelites are most easily seen on the north-western margin of the extensive exposures.

In these exposures a composite foliation of bedding and cleavage (probably of more than one generation - see notes on locality 4B) generally dips steeply (50–90°) to the SE. A linear structure of probable D2 age lies within the foliation plane. Shallower dips of the composite foliation, some of them to the NW, occur locally, and are seen to be associated with fairly open folds or kinks with flat-lying axes striking NE–SW. Some of these folds have axial planes dipping NW with congruent crenulations of the mica schistosity; they are probably D4 structures. However, other folds with similar orientations of fold axes have axial planes dipping SE and appear to belong to a fold set which is not as widely developed.

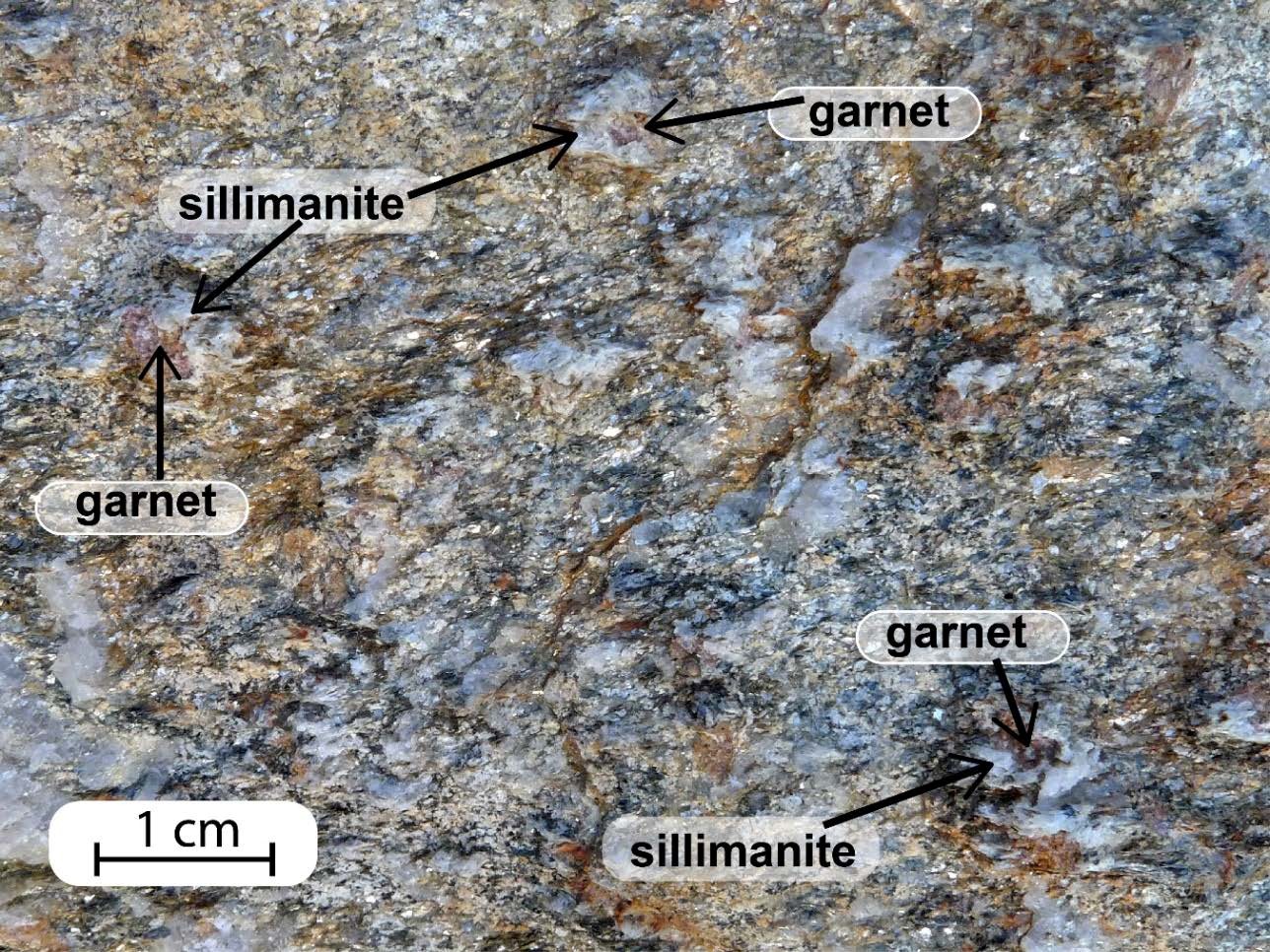

The lithology is dominantly semi-pelitic in composition and formed of grey-green mica schists. Garnet is present, but staurolite and kyanite are exceedingly rare. Sillimanite may be found on careful searching, and would probably be found to be widespread with extensive thin- sectioning. The sillimanite is of the fibrolitic variety, as elsewhere in Glen Esk, and is easily seen in the field in two situations.

- As welts and knots of tiny fibres which dominantly show a fairly smooth silky or waxy appearance on clean weathered surfaces. Such welts may be a centimetre long and are usually greyish-white, sometimes with a greenish tinge.

- As upstanding 'blobs' of fibrolite, 0.5 to 2.0 cm across on weathered surfaces and typically surrounding garnets

(Figure 10) .

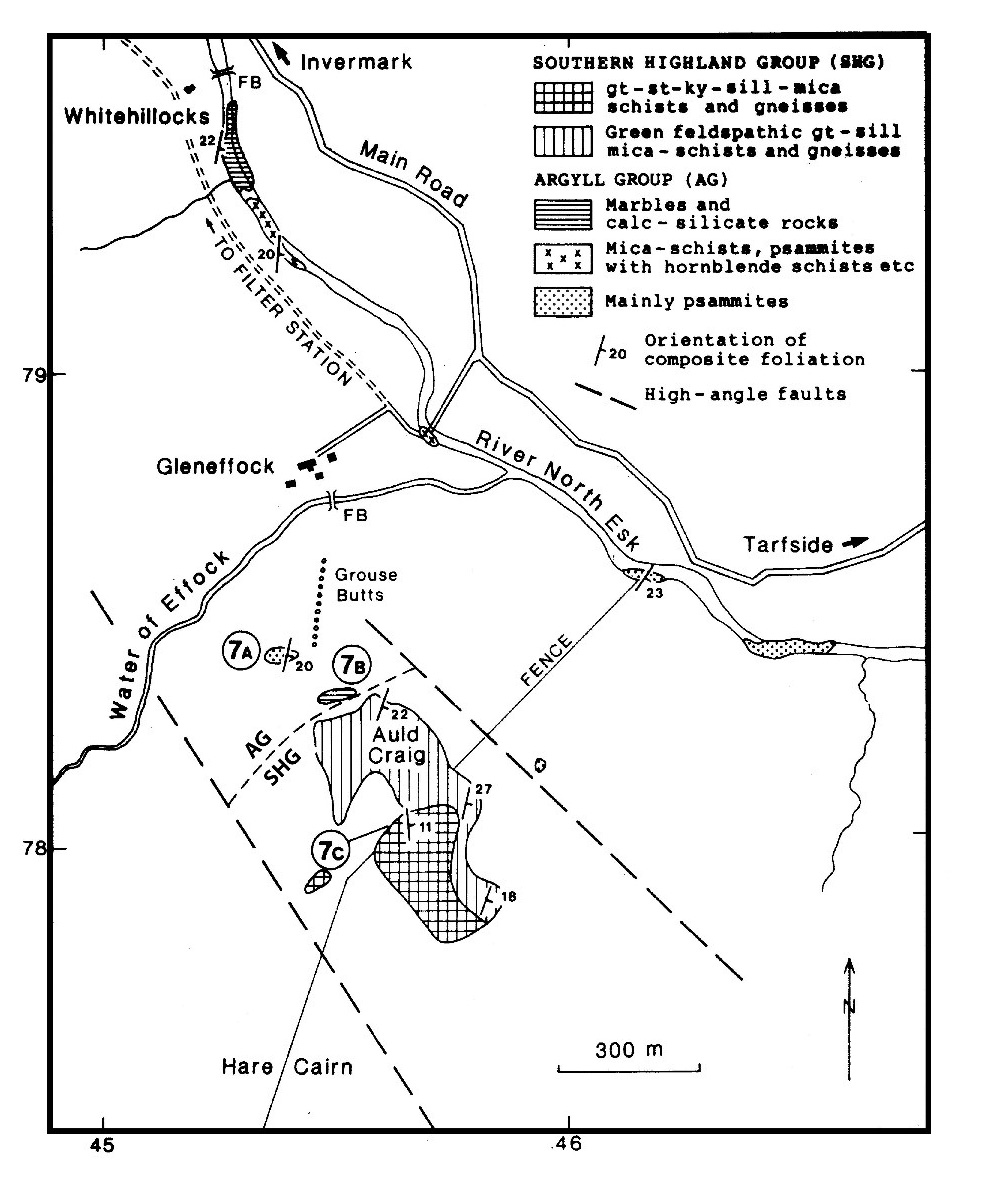

Locality 7. Sillimanite zone by Glen Effock [NO 456 780]

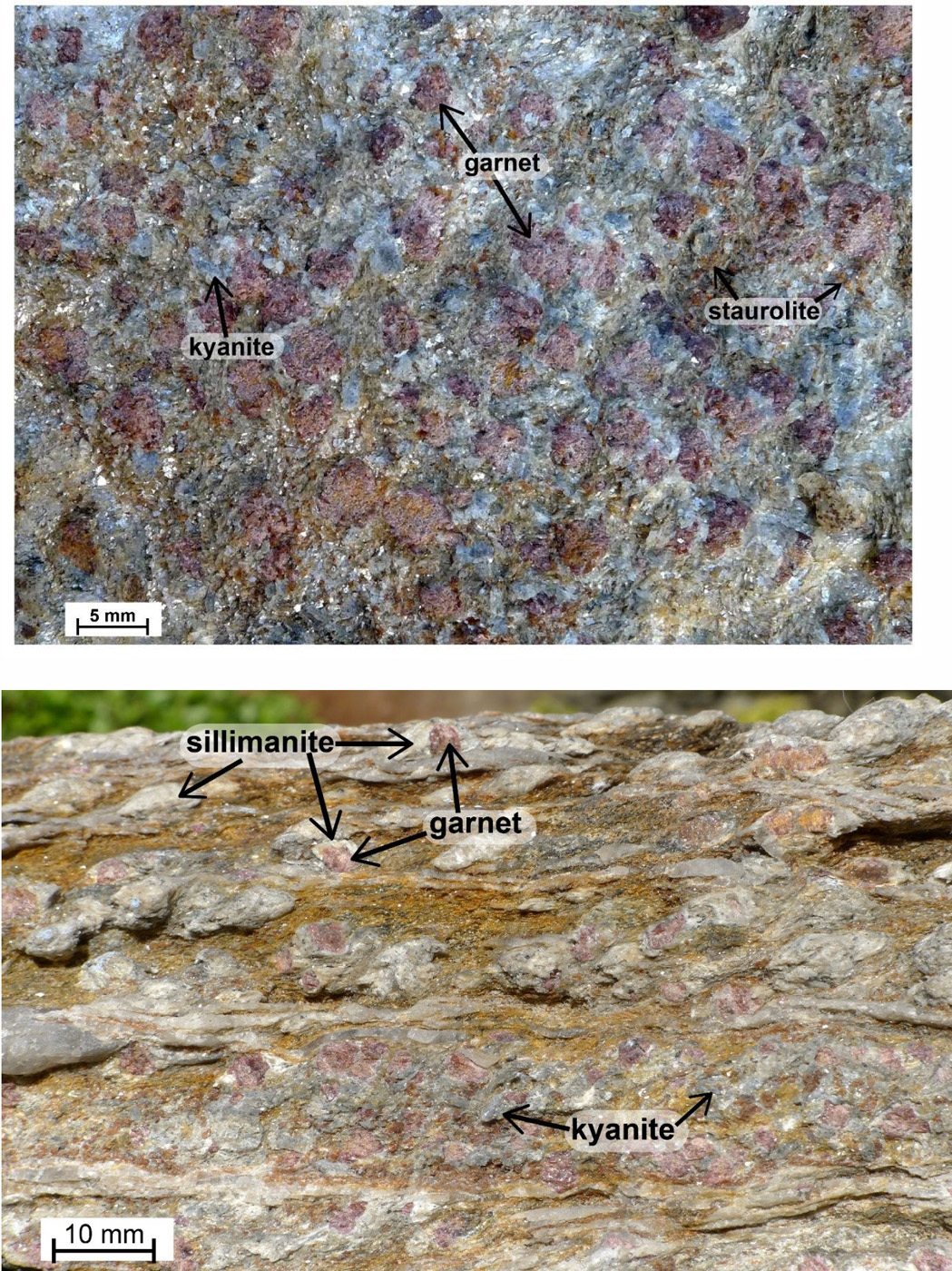

This locality has a greater variety of sillimanite-bearing rocks than those at locality 6, and includes schists/gneisses containing garnet, staurolite and kyanite. The best exposures with these index minerals occur in the

From Craigoshina drive NW up the road, past the Retreat to the village of Tarfside. The Retreat has a museum, craft shop and tea room. From Tarfside follow the signs for Invermark, taking a sharp left turn just over the bridge in Tarfside. The road/track for Glen Effock farm leaves the Invermark road 4 km from Tarfside, and there is sufficient space for a motor coach to turn in the farmyard. Ask permission for parking and access at the farmhouse.

From the farmyard walk south to cross the Water of Effock by a footbridge, and then commence the ascent of Auld Craig

Throughout the Auld Craig exposures the composite foliation (bedding and cleavages) dips generally E or SE at about 20°, but there are abundant minor folds and the structural sequence of Harte and Johnson (1969) is developed. D3 structures form a particularly extensive group of close to tight folds, with axial planes dipping gently in an easterly or southerly direction. In mica schists there is usually an axial plane cleavage (often a schistosity) to the D3 minor folds, which passes into sub-parallelism with the composite foliation on the fold limbs. In psammites, a grain alignment fabric (D1 or composite D1/D2) may usually be seen folded around the D3 hinges. A D2 ribbing lineation may be seen on the surfaces of psammitic beds or thin quartz veins (subparallel to the composite foliation); it typically plunges gently to the SE and may occasionally be seen to be folded around D3 folds. D4 structures are largely limited to crenulations of the mica-schistosity with axes sub-horizontal and striking NE–SW, whilst axial planes dip NW.

Locality 7A (Figure 11)

The lithology is dominantly of psammitic rocks, and these are much nearer to quartzites than the rather micaceous and feldspathic psammites seen at earlier localities lower down the Glen.

This change of character is a typical difference between the Argyll and Southern Highland Groups in Glen Esk. A less conspicuous, but nonetheless distinctive, feature of the

Locality 7B

Lies about 150 m SE of 7A and is formed of low-lying weathered exposures of quartzose marble and calc-silicate rock. These exposures at 7A and 7B are characteristic of the quartzitic psammites and meta-limestones which form an essential part of the local 'Tarfside Limestone and Quartzite Group' (Harte 1979). On the basis of lithology this 'Group' is correlated with the upper part (Loch Tay Limestone and Ben Lui Schists) of the

Locality 7C

From locality 7B, the party should head uphill southwards, examining the western corner of the main crags of Auld Craig, and then head eastwards above the main face of the crags to a partially broken fence

The fairly monotonous green quartz-feldspar- mica schists/gneisses of Auld Craig are representative of the 'Craig Dullet lithology', which forms the lowermost unit of the 'Effock-Lethnot Group' in Glen Esk (Harte 1979). This unit overlies the 'Tarfside Limestone and Quartzite Group' (TLQG) rocks, representatives of which were seen at localities 7A and 7B. Correlation of the Effock-Lethnot Group with the Dalradian

Above the main face of the Auld Craig crags, follow the fence

Summary of mineral assemblages across Barrow's Zones

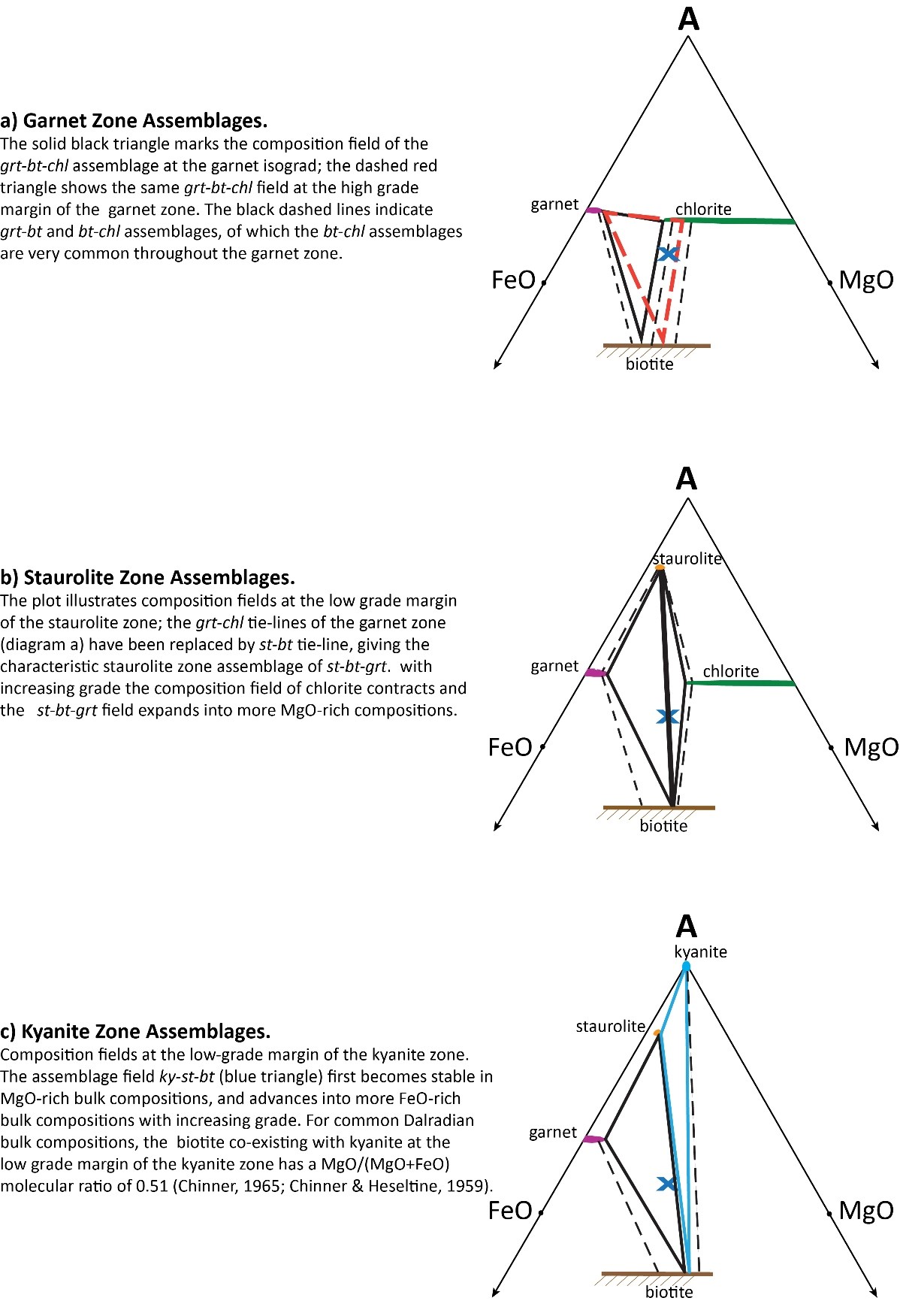

The changes in the mineral assemblages across the Glens Clova-Lethnot-Esk region of Barrow's Zones are summarized in

In the staurolite zone

Thus, in abbreviated net reaction terms in AFM space

GARNET ZONE: chlorite → garnet + biotite

STAUROLITE ZONE: garnet + chlorite → staurolite + biotite

KYANITE ZONE: staurolite → kyanite + biotite

In both the kyanite and the sillimanite zones the Al2O3 rich pelitic rocks quite often contain both garnet and staurolite as well as biotite and kyanite and/or sillimanite. In the pure KFMASH system this implies extra phases beyond those predicted by the phase rule. This is usually explained by suggesting that extra chemical components (in particular MnO in garnet, and ZnO in staurolites) lead to the stabilization of extra phases. When we reach the sillimanite zone we can find kyanite and sillimanite co-existing, which is commonly attributed to very sluggish kinetics of the polymorphic kyanite to sillimanite transition. It is in fact more common to find sillimanite forming haloes around garnet than directly replacing kyanite

Considering the abundant occurrence of kyanite in haematite-rich schists, as described under locality 5; it is evident that the effectively high M/FM, (MgO/(MgO+FeO), of these schists places them within the bulk composition field of kyanite+biotite assemblages in

The sequences of mineral assemblages and reactions described above, might be compared with those seen on the Stonehaven coast section (Harte et al. 2015, Aberdeen Geological Society website). Two striking differences may be noted:

- Kyanite does not occur in the Stonehaven section and one passes directly from staurolite zone assemblages to the same assemblages containing sillimanite (Chinner 1966; Booth 1984).

- The transition from garnet to staurolite zone assemblages at Stonehaven involves an additional zone where chloritoid+biotite assemblages occur (Harte and Hudson 1979). Thus the garnet-chlorite tie-line on the Stonehaven coast section is first broken by the development of a chloritoid-biotite tie-line. The critical chloritoid+biotite assemblage has not been found in the main part of Glen Esk; nor in Glen Lethnot and Glen Clova.

Both of these differences may be explained by pressures being lower near Stonehaven compared with further west. In calibrated pelite petrogenetic grids, chloritoid+biotite assemblages have a distinct upper pressure limit (Harte, 1975b, Harte and Hudson 1979; Powell and Holland 1990; Droop and Harte 1995; White et al. 2014). Using calculated pressures and temperatures based on specific mineral reactions and compositions, Vorhies and Ague (2011) also find lower pressures on the Stonehaven coast section compared to the region of Glen Clova and Glen Esk.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank: Sumit Chakraborty, Tim Dempster, Doug Fettes, Thomas Fockenberg, Donald Stewart and Rachel Wignall for reading parts of this guide and making helpful comments.

References

Ague, J.J. & Baxter, E.F. 2007. Brief thermal pulses during mountain building recorded by Sr diffusion in apatite and multicomponent diffusion in garnet. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 261, 500–516.

Ashworth, J.R. (1972). Migmatites of the Huntly-Portsoy area, north-east Scotland. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge.

Atherton, M.P. & Brotherton, M.S. (1972). The composition of some kyanite-bearing regionally-metamorphosed rocks from the Dalradian. Scottish Journal of Geology 8, 203–213.

Barrow, G. (1893). On an intrusion of muscovite-biotite gneiss in the south-east Highlands of Scotland, and its accompanying metamorphism. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 49, 330–358.

Barrow, G. (1898). On the occurrence of chloritoid in Kincardineshire. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 54, 149–156.

Barrow, G. (1912). On the geology of Lower Deeside and the southern Highland Border. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 23, 274–290.

Baxter, E.F., Ague, J.J. & Depaolo, D.J. (2002). Prograde temperature-time evolution in the Barrovian type-locality constrained by Sm/Nd garnet ages from Glen Clova, Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society London 159, 71–82.

Bluck, B.J. (2010). The Highland Boundary Fault and the Highland Boundary Complex. Scottish Journal of Geology 46, 113–124.

Bluck, B.J. (2011). Reply to the discussion by Tanner on 'The Highland Boundary Fault and the

Booth, J.E. 1984. Structural, stratigraphic and metamorphic studies in the SE Dalradian Highlands. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Edinburgh.

Chinner, G.A. (1960). Pelitic gneisses with varying ferrous/ferric ratios from Glen Clova, Angus, Scotland. Journal of Petrology 1, 178–217.

Chinner, G.A. 1961. The origin of sillimanite in Glen Clova, Angus. Journal of Petrology 2, 312–323.

Chinner, G.A. (1966). The distribution of pressure and temperature during Dalradian metamorphism. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 122, 159–186.

Chinner, G.A. (1967). Chloritoid and the isochemical character of Barrow's Zones. Journal of Petrology 8, 268–282.

Chinner, G.A. & Heseltine, F.J. (1979). The Grampide Andalusite/Kyanite Isograd. Scottish Journal of Geology 15, 117–127.

Dempster, T.J. (1985). Uplift patterns and orogenic evolution in the Scottish Dalradian. Journal of the Geological Society London 142, 111–128.

Dempster, T.J., Hudson, N.F.C & Rogers, G. (1995) Metamorphism and cooling of the NE Dalradian. Journal of the Geological Society London 152, 383–390.

Dempster, T.J., Rogers, G., Tanner, P.W.G., Bluck, B.J., Muir, R.J., Redwood, S.D., Ireland, T.R. & Paterson, B.A., (2002). Timing of deposition, orogenesis and glaciation within the Dalradian rocks of Scotland: constraints from U–Pb zircon ages. Journal of the Geological Society London 159, 83–94.

Droop, & Harte, B. (1995) The effect of Mn on the phase relations of medium grade pelites: constraints from natural assemblages on petrogenetic grid topology. Journal of Petrology 8, 1549–1578.

England, P.C. & Richardson, S.W. (1977). The influence of erosion upon the mineral facies of rocks from different metamorphic environments. Journal of the Geological Society London 134, 201–214.

England, P.C. & Thompson, A.B. (1984). Pressure–temperature-time-paths of regional metamorphism. I. Heat transfer during the evolution of regions of thickened continental crust. Journal of Petrology, 25, 894–928.

Ethington, R.L. (2008). Conodonts from the Margie Limestone in the

Fettes, D.J. (1970). Relation of cleavage and metamorphism in the Macduff Slates. Scottish Journal of Geology 7, 248–253.

Gillen, C. & Trewin, N.H. (2015). Dunottar to Stonehaven and the Highland Boundary Fault. Geological Society of Aberdeen website.

Gould, D. (2001). Geology of the Aboyne District. Memoir of the British Geological Survey, Sheet 66W, Scotland.

Harris, A.L., Pitcher, W.S., 1975. The

Harris, A.L., Bradbury, H.J. & McGonical, M.H. (1976) The evolution and transport of the Tay nappe. Scottish Journal of Geology 12, 103–113.

Harte, B. (1966). Stratigraphy, structure and metamorphism in the south-eastern Grampian

Highlands of Scotland. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Cambridge.

Harte, B. & Johnson, M.R.W. (1969). Metamorphic history of Dalradian rocks in Glens Clova, Esk and Lethnot, Angus, Scotland. Scottish Journal of Geology 5, 54–80.

Harte, B. (1975a) Displacement of the kyanite 'isograd' by local variations of oxygen fugacity within pelitic schists in Glen Lethnot, Angus, Scotland. EOS, Program & Abstracts of Spring AGU 1975, V60.

Harte, B. (1975b). Determination of a pelite petrogenetic grid for the eastern Scottish Dalradian. Yearbook of the Carnegie Institute, Washington 74, 438–446.

Harte, B. (1979). The Tarfside Succession and the Structure and Stratigraphy of the Eastern Scottish Dalradian Rocks. In: The Caledonides of the British Isles – reviewed. (Harris, (A.L., Holland, C.H., Leake, B.E., Eds.), Geological Society of London Special Publication 8, 221–228.

Harte, B. & Hudson, N.F.C. (1979). Pelite facies series and the temperatures and pressures of Dalradian metamorphism in eastern Scotland. In: The Caledonides of the British Isles reviewed. (Harris, A.L., Holland, C.H. & Leake, B.E., Eds.). Geological Society of London Special Publication 8, 323–337.

Harte, B., Booth, J.E., Dempster, T.J., Fettes, D.J., Mendum, J.R. & Watts, D. (1984). Aspects of the post-depositional evolution of Dalradian and

Harte, B., Dempster, T.J., 1987. Regional metamorphic zones: tectonic controls. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A 321, 105–127.

Harte, B., Booth, J.E. & Fettes, D.J. (2015). Stonehaven to Findon: Dalradian Structure and Metamorphism. Geological Society of Aberdeen website.

Henderson, W.G. & Robertson A.H.F. (1982) The Highland Border rocks and their relation to marginal basin development in the Scottish Caledonides. Journal of the Geological Society, London 139, 433–450.

Horne, (1884). The origin of the andalusite-schists of Aberdeenshire. Mineralogical Magazine 6, 98–100.

Hudson, N.F.C. & Johnson, T.E. (2015) Macduff to Whitehills – Buchan type regional metamorphism. Geological Society of Aberdeen website.

Irvine, D.R. & Barrow G. (1897). Banchory Sheet 66. Geological Survey of Scotland.

Johnson, M.R.W. & Harris, A.L. (1967). Dalradian?Arenig relations in part of the Highland Border, Scotland, and their significance in the chronology of the Caledonian orogeny. Scottish Journal of Geology 3, 1–16.

Johnson, T.E. & Fischer, S. (2015) Cairnbulg to Inzie Head – Dalradian migmatites. Geological Society of Aberdeen website.

Johnson, T.E. & Knellar, B.C. (2015) The Dalradian of Fraserburgh. Geological Society of Aberdeen website.

McLellan, E.L. 1985. Metamorphic reactions in the kyanite and sillimanite zones of the Barrovian type area. Journal of Petrology, 26, 789–818.

Oliver, G.J.H., Chen, F., Buchwald, R. & Hegner, E. (2000). Fast tectonometamorphism and exhumation in the type area of the Barrovian and Buchan zones. Geology 28, 459–462. Phillips, E.R. & Auton, C.A. (1997). Ductile fault rocks and metamorphic zonation in the Dalradian of the Highland Border SW of Stonehaven, Kincardineshire. Scottish Journal of Geology 33, 83–93.

Pringle, J. (1941). On the relationship of the Green Conglomerate to the Margie Grits in the North Esk, near Edzell; and on the probable age of the Margie Limestone. Trans. geol. Soc. Glasgow, 20, 136–40.

Read, H.H., 1928. The Highland Schists of middle Deeside and east Glen Muick. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 55, 755–772.

Richardson, S.W. & Powell, R. (1976). Thermal causes of Dalradian metamorphism in the central Highlands of Scotland. Scottish Journal of Geology, 12, 237–268.

Robertson, S. (1991). Older granites in the south-eastern Scottish Highlands. Scottish Journal of Geology 27, 21–26.

Robertson, S. (1994). Timing of Barrovian metamorphism and 'Older Granite' emplacement in relation to Dalradian deformation. Journal of the Geological Society, London 151, 5–8.

Shackleton, R.M. (1958). Downward-facing structures of the Highland Border. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, London 113, 361–392.

Stephenson, D. and Gould, D. (1995) British regional geology: the Grampian Highlands (4th edition). HMSO for British Geological Survey.

Stephenson, D., Mendum, J.R., Fettes, D.J. and Leslie, A.G. 2013a. The Dalradian Rocks of Scotland: an introduction. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association, 124, 3–82.

Stephenson, D., Mendum, J.R., Fettes, D.J., Smith, C.G., Gould, D., Tanner, P.W.G. & Smith, R.A. (2013b). The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian Highlands of Scotland. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 124, 318–392.

Tanner, P.W.G., Thomas, C.W., Harris, A.L., Gould, D., Harte, B., Treagus J.E. & Stephenson, D. (2013). The Dalradian rocks of the Highland Border region of Scotland. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 124, 215–262.

Tanner, P.W.G. & Bluck, B.J. (2011). Discussion of 'The Highland Boundary Fault and the Highland Boundary Complex' by B.J. Bluck Scottish Journal of Geology 46, 113–124. Scottish Journal of Geology 47, 89–93.

Tanner, P.W.G. & Sutherland, S. (2007). The

Thompson, J.B.Jr. (1957). The graphical anlysis of mineral assemblages in politic schists. American Mineralogist 42, 842–858.

Tilley, C.E. (1925). A preliminary survey of metamorphic zones in the southern Highlands of Scotland. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society London 81, 100–110.

Viete, D.R., Hermann, J., Lister, G.S. & Stenhouse, I.R. (2011a). The nature and origin of the Barrovian metamorphism, Scotland: diffusion length scales in garnet and inferred thermal time scales. Journal of the Geological Society, 168, 115–132.

Viete, D.R.,.Forster, M.A. & Lister, G.S. (2011b). The nature and origin of the Barrovian metamorphism, Scotland: 40Ar/39Ar apparent age patterns and the duration of metamorphism in the biotite zone. Journal of the Geological Society, 168, 133–146.

Viete, D.R., Oliver, G.J.H., Fraser, G.L., Forster, M. & Lister, G.S. (2013). Timing and heat sources for the Barrovian metamorphism, Scotland. Lithos, 177, 148–163.

Voerhies, S.H. & Ague, J.J. (2011). Pressure–temperature evolution and thermal regimes in the Barrovian zones, Scotland. Journal of the Geological Society, 168, 1147–1166.

White, R.W., Powell, R., Holland, T.J.B., Johnson, T.E. & Green, C.R.E. (2014). New mineral activity-composition relations for thermodynamic calculations in meta-pelitic systems. Journal of Metamorphic Geology, 32, 261–286.