Chapter 6 The succession in the Mona Complex

Introductory

Local successions can be made out in the several isolated regions and inliers of the Mona Complex, but these must all be brought into harmony before a general succession throughout the Complex can be established. Now the scheme of colours and symbols that has been adopted on the one-inch map for the various sub-divisions of the Complex has been applied throughout, the New Harbour Beds of Holyhead, for example, being coloured and lettered with the

A general scheme of the succession will, then, be put forward, with brief accounts of the sections upon which it is founded.

Correlations within the Complex

Such fossils as have been found in the Mona Complex, though of great interest, cannot yet be utilised for purposes of correlation; and correlations of unfossiliferous rocks may, even when they are comparatively undisturbed, be vitiated by change of facies. Where disturbance is great, and metamorphism has set in, the risk is still greater; and, therefore, the correlations which will now be set forth are put forward with reserve. The geographical extent of the exposed portions of the Complex, however, is not large, hardly affording space for change of facies so great as to prevent recognition. And, what is much more important, though moderate changes of facies must be admitted, yet the greater subdivisions of the Complex contain members with persisting characters, by whose presence the identity of the changing members can be recognised.

The New Harbour Group — The

| South Stack Series (Llwyn Beds) | Coeden Beds | |

| { |

Pelitic | Bodelwyn Beds} |

| {Soldier's Point Beds | Psammitic (with lavas and jaspers) | Lynas Beds} |

| Church Bay Tuffs | Skerries Grits |

thus confirming the correlation in a remarkable manner, and showing that the change of facies is less than at first sight appears. This correlation is of great importance, as, once established, it adds weight to the evidence for all the other identifications of groups in the Northern Region.

The Skerries Group — The Skerries Grits resemble the Church Bay Tuffs, with part of which they are correlated, in that their matrix is a pyroclastic porcellanous epidosite of the same nature as that which often makes up the body of the latter; in which, when grits occur (as on the Rhos-y-cryman coast) they are of thorough Skerries type. An extraordinary massiveness, with occasional impersistent bedding, is a marked character of both. Most important, however, is the fact that both of them contain fragments of the same peculiar felsitic and granitoid micropegmatites, which are developed on such a great scale at The Skerries, indicating that both drew their materials from the same supply. It is therefore inferred that the Sherries Grits are a northern, gritty facies of part of the Church Bay Tuffs; and, as their quartz (see p. 59) is largely pyroclastic, the difference is less than appears at first sight. In the Trwyn Bychan band, Church Bay types act as a matrix to the part of the Skerries Grits with which they alternate. Reasons have already (p. 62) been given for referring the Tyfry Grits to the Skerries Group, in which case they must be regarded as an eastern facies of the Church Bay Tuffs. The pyroclastic nature of some of the hornfels of the Coedana granite has already been dwelt upon; and the field-aspect of the crypto-crystalline variety often recalls that of the Church Bay Tuffs. Thin short basic bands occur in both (see pp. 94, 284, 334). Where least altered, the porcellanous epidosite of those tuffs is constantly suggested, and there is the same rare and impersistent bedding. The hornfels as a whole cannot possibly represent any of the well-stratified members of the Complex, and so the massive Church Bay Tuff is the only member which it can represent, a conclusion confirmed by its relations to the rocks of Bodafon.

The

The Fyllyn Group, in anything like its original condition, is known only at the Fydlyn,Inlier. No other facies has as yet been detected, though there is reason to suspect (see p. 233) that it thickens greatly in a south-easterly direction.

The Penmynydd Zone of Metamorphism — Evidence as to the horizon of the recognisable parts of the Peiimynydd Zone has already been given in considering the origin of its rocks. The sedimentary component is undoubtedly the

The Gneisses — With regard to the mutual relations of the gneisses, there need be no hesitation in regarding those of all the several inliers as essentially one and the same formation or metamorphic zone. The same albite-granites, and the same albite- oligoclase-biotite-gneisses, with the type-mineral sillimanite, are common to them all.

The Coedana granite, with its porphyritic orthoclase and hornfels-alteration, is regarded as distinct—a later intrusion from a potassic magma.

Order of succession

Evidence as to the order of succession of the greater clastic subdivisions of the Complex is to be found in its western tracts to the south of the Carmel Head thrust-plane, untroubled by any change of facies. But the link between the Skerries and New Harbour Groups is much better exposed in the Northern Region, so that if the correlations just now made have been correctly made, the chain of evidence is complete. In which direction that succession should be read, which, that is to say, is its true order chronologically, will be considered further on.

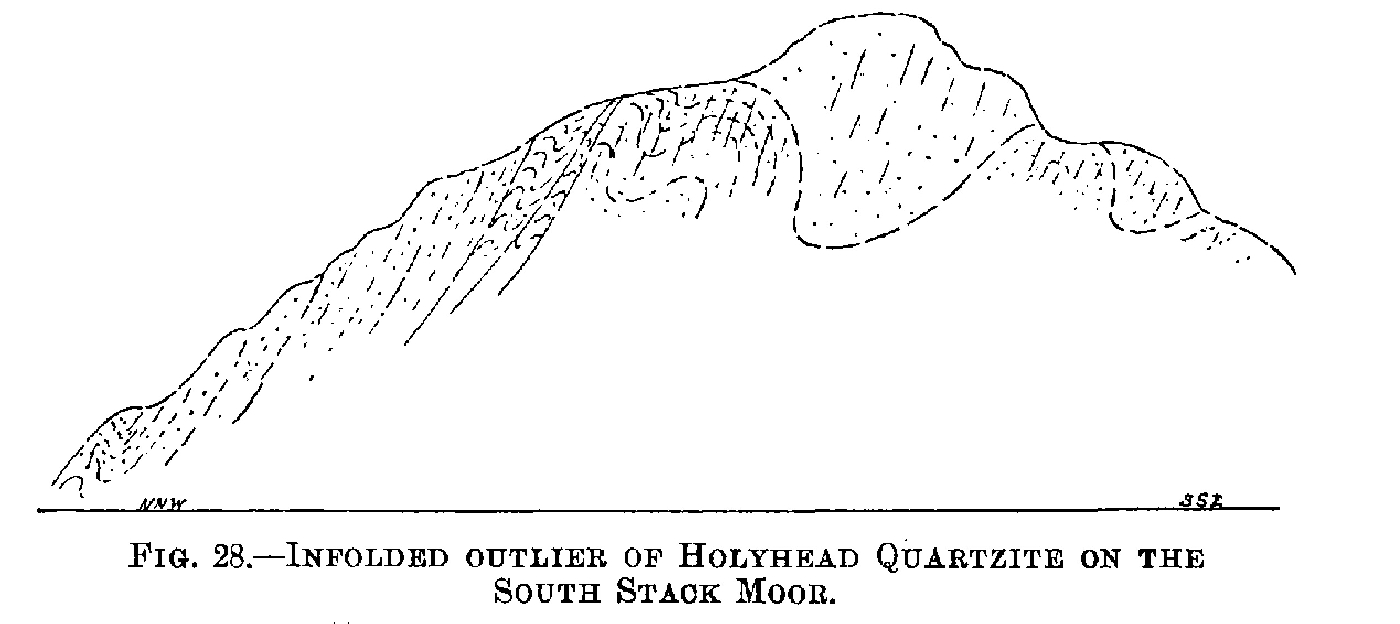

The key to the succession is in Holy Isle.

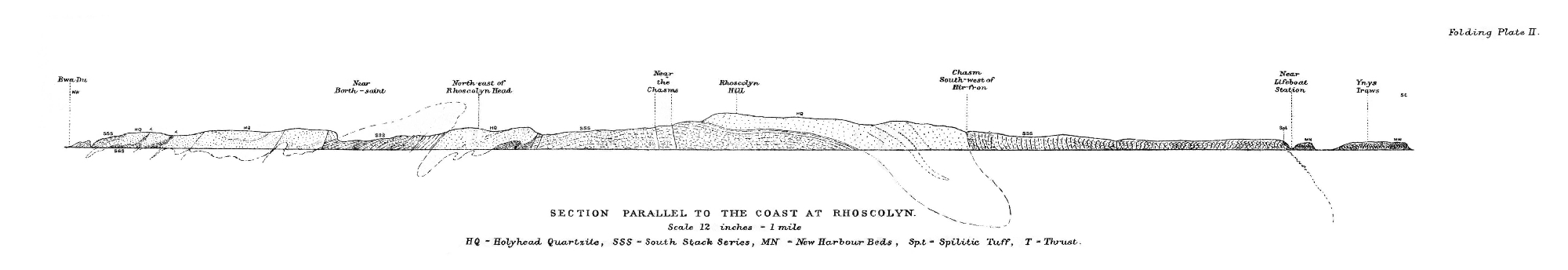

South Stack Series and New Harbour Beds — The South Stack Series (and always its Llwyn member) is also seen, at a number of places, in relation to the Green-mica-schists, and the junction is clearly exposed at three sections near Stryd; at the large 'H' to the west-south-west (Cae-allt-wen. crag of six-inch map); by the dyke on the Porth Dafarch road; at and east of Bodwradd; by the Lifeboat Station, Rhoscolyn; in Borth Wen; and at three sections on the curve thence to Pentre-iago. At all these sections there is a rapid but unbroken change from the one type of sedimentation to the other. Further, at all of them (except the northern Stryd section, which is not quite deep enough—see p. 266), and at some ten places more, where, without actual exposure of the junction, the two series are seen close together, a little albitic basic band

But if the South Stack Series be adjacent to_the quartzite on the one hand, and to the New Harbour Beds on the other, they must lie between those two, which they can actually be seen to do between Rhoscolyn Hill and the Lifeboat Station, so that the succession in Holy Isle is:

South Stack Series

New Harbour Group

New Harbour and Skerries Groups. At Porth-y-defaid the New Harbour Beds are succeeded by the main mass of the Church Bay Tuffs: but there is evidently a rupture, for Gwna Beds are brought against the same line inland, and a (later) dislocation is actually visible on the low foreshore. Yet on the north side of this there is a 50-foot band of green-mica-schist, finer than that to the south, but, like it, containing thin seams of jaspery phyllite. It would appear, therefore, that the dislocation is dying out seawards and that the margin of the New Harbour Beds just escapes upon its further side. This band is highly epidotic, and graduates in clear exposures into the Church Bay Tuffs, which also contain thin purple seams for a few yards more. At their northern end close to Yr-ogo-goch (though the New Harbour Beds do not appear) the tuffs contain many thin bands of pale bedded jaspers and green grits like those found at the margin of the New Harbour Group. Bands of the tuff, somewhat metamorphosed but easy of recognition, alternate with the New Harbour Beds (there also containing purple phyllites) at Brwynog. A few yards east of Llanddeusant Church a massive epidositic tuff of Church Bay type appears among, and graduates into, the Green-mica-schists; and a very fine one with wriggling vcinlets like those of Llanrhyddlad behaves in the same way on the coast at Penial. Whether these be nips of the main tuffs is not known, but even if not, they show that explosions of the same kind were taking place during the deposition of that part of the New Harbour Group. At the Garn, typical Church Bey Tuff, highly sheared, succeeds the Green-mica-schist all across the inlier

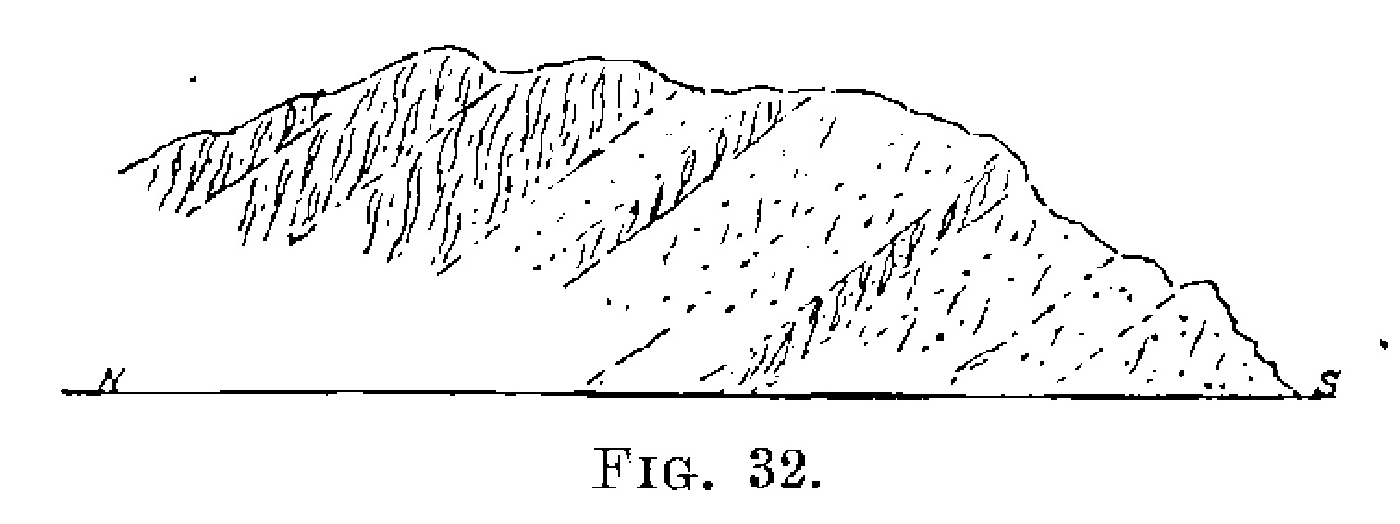

Passing to the Northern Region, it will be found that the relations between the

Along the southern side of the main outcrop of the Skerries Grits, especially at the 'a' of 'Llanfechell', at Bwlch, and at Pen-yr-orsedd, the

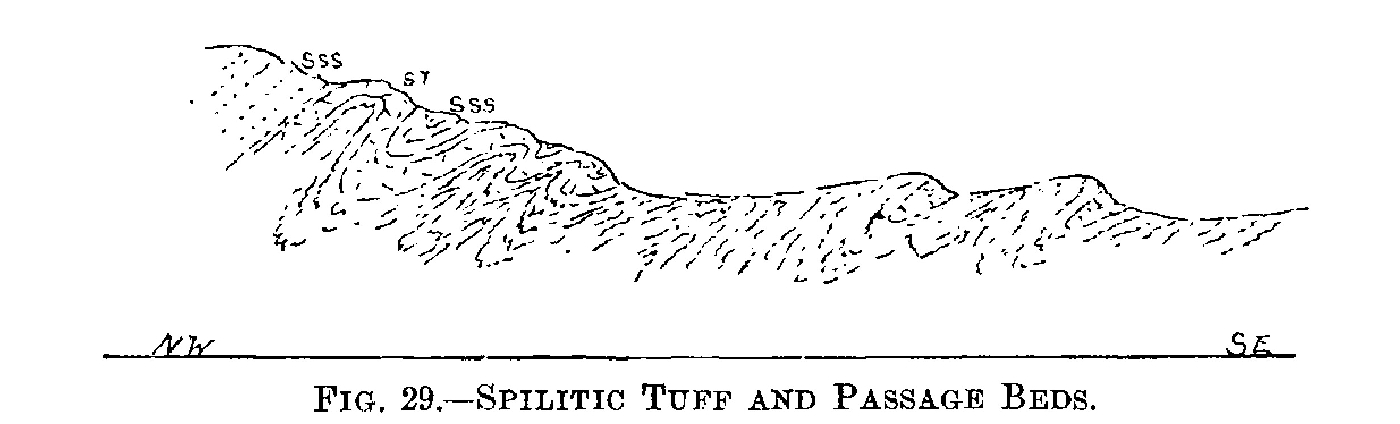

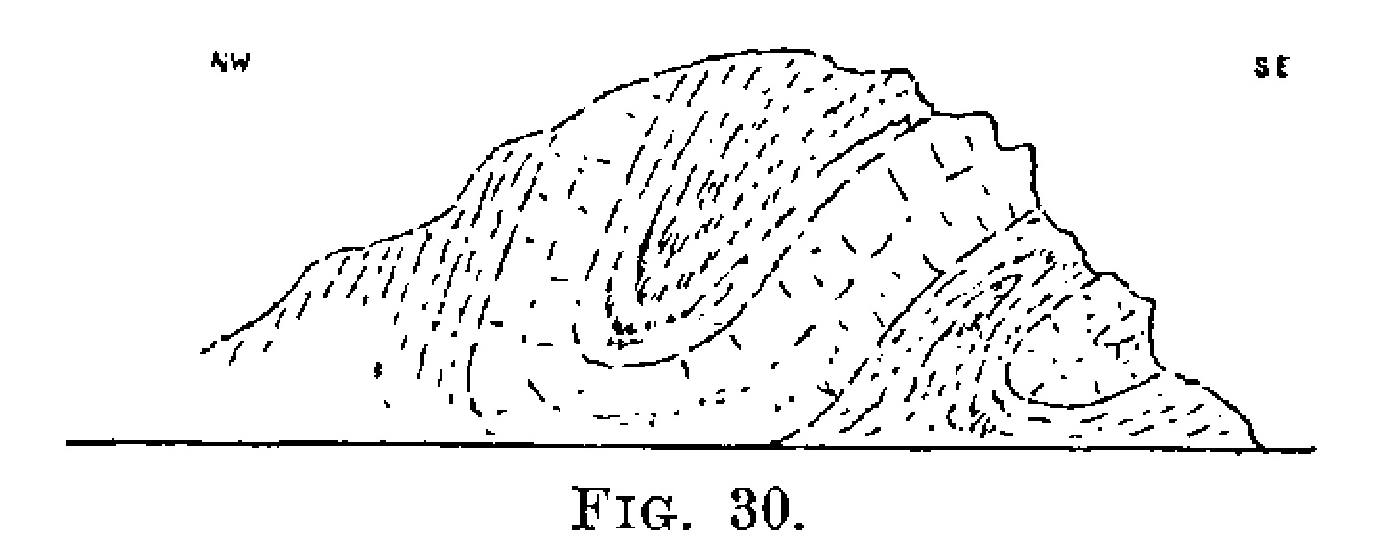

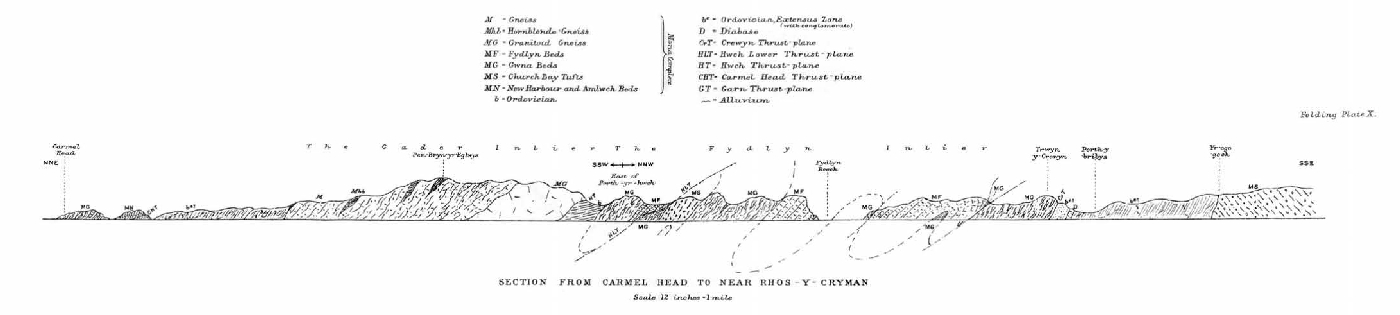

Skerries and Gwna Groups — That the Gwna Beds adjoin the Skerries Group is clear on both sides of the Carmel Head thrust-plane. At Brwynog, Rhyd-wyn and Gareg-Iwyd to the south, and at Mynachdy, Caerau, and Llyn Llygeirian to the north of it, epidositic ashy matter of Church Bay and Skerries type is inextricably involved with Gwna Green-schist. At the south end of Porth Swtan the junction is exposed. The foreshore west of the '73' level is composed of typical Church Bay Tuff, in which are small fragments of a pink felsite. At the foot of the cliff close by, where the roadway comes down to the beach, the body of the rock is identical with the decomposed parts of the tuff and, like it, homogeneous, with fresh portions that are good epidosites. In this material the first Gwna quartzites appear, above them foliation sets in, with broken banding, and the whole passes rapidly into decomposing Gwna mélange with many small quartzites, but still ashy between them in places. On the headland south of Porth-yr-hwch

Such are the best sections across this junction. They leave no doubt that the Gwna lies next to the Skerries Group in the succession, graduating into it. Gwna mélange (pp. 354–6) appears within the

Passage-beds, intermediate in character between Skerries and Gwna type, are well seen about Nant-newydd, Llangefni. At Llangristiolus, 160 yards east of the late dyke and 60 yards north of the footpath to Llan-fawr, is a craglet escarpment that shows bedding well. At its foot are ashy grits with green partings, in which are purple seams just as in the undoubted

At Mynydd Bodafon the massive hornfels graduates into the beds (themselves converted into hornfels) that 'underlie' the Bodafon quartzite. Here also, then, The Skerries and Gwna Groups adjoin and alternate with each other; thus confirming, moreover, the identifications of the hornfels and the Bodafon quartzite with members of those groups.

Gwna and Fydlyn Groups — At Fydlyn the gritty felsitic tuffs alternate for a few yards with Gwna Beds

The Coeden Beds — The position of the Coeden Beds may now be considered with advantage. It has been shown that they are more nearly related lithologically to the Llwyn part of the South Stack Series than to any other member of the Complex, and that they cannot be identified with the Skerries Grits. Along their northern margin they adjoin the

Correlating, then, the Northern Region with the remainder of the Complex, we have

| The Bedded Succession | |

| South | North |

| South Stack Series | Coeden Beds |

| New Harbour Beds | |

| Church Bay Tuffs | {Skerries Grits |

| {Church Bay Tuffs | |

| Gwna Beds | Gwna Beds |

| Fydlyn Group | |

It will be seen that the correlations made on lithological grounds are sustained in every case by the positions of the beds in the respective orders of succession. The foregoing members constitute that portion of the Complex which will be referred to as The Bedded Succession'.

The Pennignydd Zone is not, indeed, a stratigraphical horizon. But we have seen (pp. 122–6) that its rocks are partly a crystalline condition of the Gwna Beds, partly altered felsite and felsitic tuff. These acid volcanic rocks, therefore, adjoined the Gwna Beds in the succession, but no such rocks are found at the junctions with the Skerries Group, or in that group itself. No facies of that group found in the Middle or Aethwy Regions could have yielded such a product as the Penmynydd acid mica-schists of those regions. The Fydlyn rocks, however, could; and we have seen that they adjoin, and that their felsitic tuffs graduate into, the Gwna sediments on their other side. The felsitic parts of the Peninyny-dd schists may, therefore, be correlated with the Fydlyn rocks.

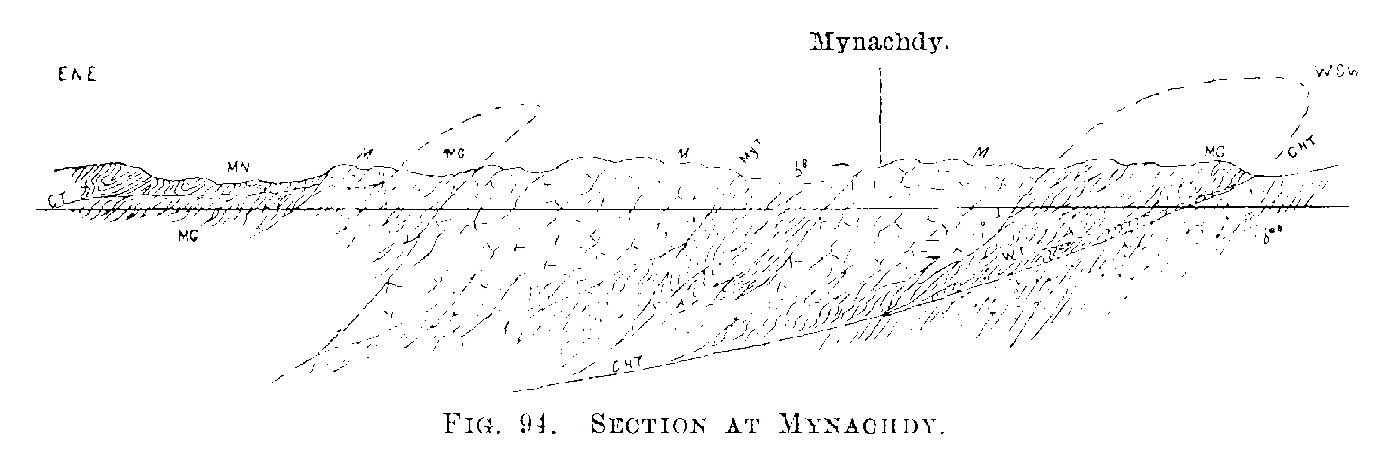

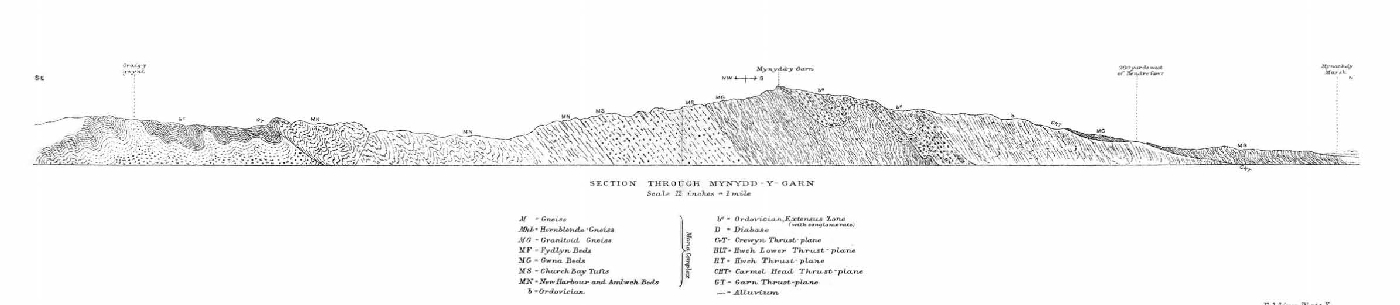

Position of the Gneisses — The position of the Gneisses remains to be considered, but our knowledge is unsatisfactory, for there are no sections displaying their original relations to any rocks of known horizons. The Nebo Inlier and those about Llanerchymedd and Bryngwran are completely isolated by Ordovician rocks. But they all lie on one great curving zone of strike, and as the small inliers are manifestly one with the great gneiss of the Middle Region, it is clear that a continuous floor of gneiss must range beneath the Ordovician rocks all through the central parts of Anglesey. The gneiss of the Gader Inlier is faulted, on the cliffs, against Gwna mélange full of lenticular grits in a slightly anamorphic matrix. The rocks are in totally different crystalline conditions, and a passage is impossible. At Mynachdy, north of the 'h' and below the drive, Gwna phyllite and quartzite are seen only about nine inches from gneiss, but there is no change in the Gwna rocks, and the junction must be a rupture. The gneiss of the Middle Region is isolated from the remainder of the Complex by the great Coedana granite. At Gwyndy it is seen very close to two of the hornfelses of that granite (which are believed to be modifications of the Church Bay Tuffs), but the change of type is abrupt and the junctions not exposed. On the Holyhead road, between Caerglaw and the ninth mile-post, gneiss and mica-hornfels strike at one another, and a passage is suggested. But again the rocks of the nearest exposures are contrasted, on the north being thorough gneiss, on the south being thorough hornfels; and as the hornfels is a little crushed in the crag that overlooks the road, there is doubtless a fault running east and west, as is indicated by the features. At Holland Arms, on the edge of the high wood, south of the 're' of 'Pentre', there is a 30-yard band of coarse micaceous gneiss along the edge of the basic ones. Just outside the wood, close to the gneiss, is a hard siliceous rock with large micas which appears to be an unusual modification of the Penmynydd schists, but it is poorly exposed and the junctions are not seen. All the known junctions are therefore either faulted, thrust, or hopelessly obscure. It is to be noted, however, that wherever gneisses appear the adjacent member of the Complex in their immediate neighbourhood is either the Gwna Beds, the Gwna-ward portions of the Sherries Group (of which the hornfels appears to be a modification), or the Penmynydd schists; never any member of the Holyhead Group. Whatever their true relations, then, they may with confidence be placed at the Gwna-ward end of the succession. And as the Fydlyn and Gwna rocks are interbedded at their junction, the Gneisses must be placed at the extreme end beyond the Fydlyn Group.

Tabular statements of the succession

The successions in the several regions and inliers are therefore as follows. And the general succession in the Complex may be taken to be as in the table given on p. 164.

Local successions

Holy Isle

South Stack Series

New Harbour Beds

Western Region

New Harbour Beds

Church Bay Tuffs

Gwna Beds (W.)

Fydlyn Inlier

Church Bay Tuffs

Gwna Beds (W.)

Fydlyn Beds

Gader Inlier

Gwna Beds Gneiss

Garn Inlier

New Harbour Beds

Church Bay Tuffs

Gwna Beds (W.)

Corwas Inlier

New Harbour Beds

(Church Bay Tuffs?)

Gwna Beds

Northern Region

Coeden Beds

Gwna Beds (W.) Gneiss

Deri Inlier

Penmynydd Zone (Gwna)

Nebo And Llanerchymedd, &c., Inliers

Gneiss

Middle Region

Gwna Beds (E.)

Penmynydd Zone (Gwna W.)

Penmynydd Zone (Fydlyn)

Gneiss

Pentraeth Inliers

Gwna Beds (E.)

Penmynydd Zone (Fydlyn)

Aethwy Region

Gwna Beds (E.)

Penmynydd Zone (Fydlyn)

Gneiss

No reason has been given, so far, for placing the

The general succession

| Group Name | Southern Facies | Northern Facies | Western Facies | Eastern Facies | |

| Penmynydd Zone of Metamorphism | Correlated in part with Fydlyn and Gwna Groups | Mica schist, quartz-schist, limestone. graphite-schist, hornblende-schist, glaucophane-schist. | |||

| Plutonic Intrusions | — | — | — | — | Coedana granite, diorite, serpentine-suite. |

| — | — | - — | — | Massive quartzite. | |

| South Stack Series (Holyhead Group) | South Stack Series 2. |

1. Coeden Beds | — | — | Massive schistose grits with partings of mica-schist. Thin-bedded ditto, ditto. |

| New Harbour Group (Holyhead Group) | New Harbour Beds 2. |

— | — | Thin tuff-schist. Fissile green-mica-schist. Gritty green-mica-schist. with bedded jasper, jaspery phyllite, and spilitic lava. | |

| Skerries Group | Church Bay Tuffs | Sherries Grits Church Bay Tuffs | — | Massive tuffs, and ashy grits and conglomerates. Bedded ashy grits in east. | |

| — | — | Gwna Beds Attenuated and chiefly sedimentary. | Gwna Beds Thick and with much volcanic matter. Black phyllite absent. | Alternating grit and phyl]ite, autoclastic mélange, and green-schist. Quartzite, limestone, graphitic phyllite, jasper, jasperry phyllite. Spilitic lava, tuff, and albite-diabase, often passing into chlorite-epidote-schists. | |

| Fydlyn Group | — | — | — | — | Acid lavas and tuffs with thin sediments. All schis tose. |

| The Gneisses | — | — | — | — | Basic and acid gneiss with granitoid matter. |

Chronological order of the succession

There seems no doubt that this is the real succession in the Complex. But nothing in the succession itself, or in the field-relations of its members; affords any evidence as to its true chronological order, except the circumstance that the Gneisses, its most deep-seated member, are found at the Fydlyn-ward end, which suggests that in that direction the lower and older beds may be at least expected. The state of alteration of the clastic members proves nothing, for, although the Gwna Beds usually display a low grade of alteration and the Holyhead Group a high one, yet in the Penmynydd Zone the Gwna Beds are as highly crystalline as anything at Holyhead.

There is, however, one piece of evidence that is of great weight, if, indeed, it be not conclusive. As well as their boulders of unknown igneous rocks, the conglomerates on The Skerries have yielded some pebbles of white quartzite and scarlet jasper. The quartzite is fine, unfoliated, and not of Holyhead but of thorough Gwna type. The jasper is unmistakable; it is the type known only in the spilitic lavas and limestones of the

There is confirmatory evidence. Fragments of quartzite of Gwna type are found in the Church Bay Tuffs, the

It will be well to tabulate the composite (and a few simple) fragments that have been found in the Complex altogether.These fragments may be seen in the following (among other) slides and specimens:

In

In South Stack Series, (E10131)

In New Harbour Beds, (E10150)

In

In Church Bay Tuffs, (E10370)

In Trwyn Bychan Tuffs, (E10513)

In Skerries Grits on Main Island, (E10384)

In East and Middle Mouse, (E9319)

The Skerries, E. (E10579)

In Tyfry Grits, (E9839)

In Gwna Grits, (E10105)

In Gwna Quartzite, (E9801)

| Jasper, granoblastic rocks, mica-schist, Gwna quartzite (?) | |

| South Stack Series | Jasper, Gwna quartzite, schistose grit, hypa-byssal albite-rocks, granoblastic rocks, mica-schist, blue quartz, tourmaline-mica-schist, granite, gneiss. |

| New Harbour Beds | Gwna quartzite, granite. |

| Amiawch Beds | Gwna quartzite, green grit, pegmatitic felsite. |

| Church Bay Tuffs and Skerries Grits | Pegmatitic felsite, pegmatitic albite-granite, Gwna quartzite, Gwna jasper, green grit, purple grit and mudstone, keratophyre and spilite, schistose grit, granoblastic rocks with mica, mica-schist. Fragments within these pebbles — Spilite and keratophyre, granoblastic rocks, mica-schist. |

| Tyfry Grits | Albite-trachyte, keratophyre, spilite, quartz-felsite, tourmaline-mica-schist, gneiss (?). |

| Gwna Grits | Keratophyre, albite-quartz-felsite, hypa-byssal albite-rocks, micropegmatite, granite, schistose grit, quartz-schist, mica-schist. |

| Gwna Quartzite | Spilite, granoblastic rocks with mica, mica-schist, tourmaline |

The green grits and the purple grits and mudstones may be from the Gwna Beds, and the keratophyres and albite-trachytes are doubtless from unexposed parts of the Gwna spilite-magma. The pebbles of the Skerries Grits (unless detached and brought into those beds by volcanic explosions) imply some degree of unconformity between the Skerries and the Gwna Groups. South of the Carmel Head thrust-plane the two groups appear too closely knit for this to be admissible. It is true that the

Turning to the other pebbles, the great igneous boulders of The Skerries indicate that acid hypabyssal rocks were then undergoing erosion, and from the size of the boulders it is clear that they were exposed to waste at some place very near The Skerries. The less deep-seated of them had been exposed somewhat earlier, small fragments of such being found in Gwna grits. They must be of great antiquity: but they cannot be in, situ anywhere in Anglesey, and their source remains unknown. The Skerries conglomerates, coarse though they be, represent only a local platform of erosion; and, of the Gwna sediments, even the coarsest are but grits. The true base of the whole clastic series of the Complex must therefore be lower down, and it still' eludes us.

Chronology of the plutonic intrusions

The

As the Serpentine-suite have suffered more deformation than the Coedana granite, their foliation being locally folded and their tremolite-schists highly anamorphic, it is reasonable to suppose that they are somewhat older. The Plutonic sequence would thus be: Peridotite, Pyroxenite, Gabbro, Granite.

The Penmynydd Zone of Metamorphism, we have seen to be later than the intrusion of the Coedana granite.

The Relations of the Gneisses to the Bedded Succession

A question that still remains over is that of the true relations of the Gneisses. It appears, from the evidence that has just been given, that they must, as far as mere position is concerned, be placed below the Fydlyn and Gwna rocks, and thus at the bottom of the whole succession. Is their metamorphism, however, the same as that which has affected all the rest of the rocks of the Complex; or are they portions of an ancient gneissic floor, whose metamorphism was produced before the deposition of any of the members of that succession? A conclusive answer cannot as yet be given to this question, but some evidence is available, and that on both sides will now be set forth.

Their proximity to the Coedana granite in the Middle Region certainly suggests that they are genetically connected with it, and that their metamorphism is, like that of the Penmynydd Zone, a part of the regional metamorphism of the whole Complex. We have seen, however, that the felspars of the two rocks are different, and that the granitoid element of the gneiss cannot be the Coedana granite. And as the Coedana hornfels is a far less deep-seated product than the gneiss, the two cannot have been produced in the same thermal zone. The diorite of Llangaffo cutting (see p. 99) appears to have been an intrusion into Fydlyn or Gwna rocks now converted into Penmynydd mica-schist, but it is very doubtful whether it can be identified with the basic portions of the gneiss. No boulders of the Gneisses have as yet been found in the Skerries conglomerates, nor have any that are undoubtedly from them been found in any member of the succession.

On the other hand, a fragment of a coarse muscovite-biotite-gneiss (E10135)

The Ancient Floor

That the Bedded Succession of the Mona Complex rests unconformably upon a yet more ancient foliated complex, whose foliation was complete, not only before the Mona metamorphism but before the deposition of the sediments now involved in that, is, however, certain. From the fragments contained in the Complex here and there, we get, even if the visible Gneisses form no part of that old floor, some dim light as to its nature, and see that it included schistose grits, mica-granulites, mica-schists, and tourmaline-mica-schists, with granitoid and also gneissose rocks.

Note — In this chapter, attention has been focussed upon the succession of the main divisions of the Complex. The relative positions of the sub-divisions have been, in several places, implied; but full evidence would have involved detail that might have rendered this chapter too intricate. Where -she positions of sub-divisions are known they have been placed in that order in the table on p. 164. The evidence will be found in chapters 8 and 10, particularly in chapter 10, and on pp. 383–5. In the latter place more precise particulars will also be given with regard to the stratigraphical horizons on which the Penmynydd metamorphism is known to develop.