Chapter 8 British Cretaceous fossil reptile sites

Introduction: Cretaceous stratigraphy and sedimentary setting

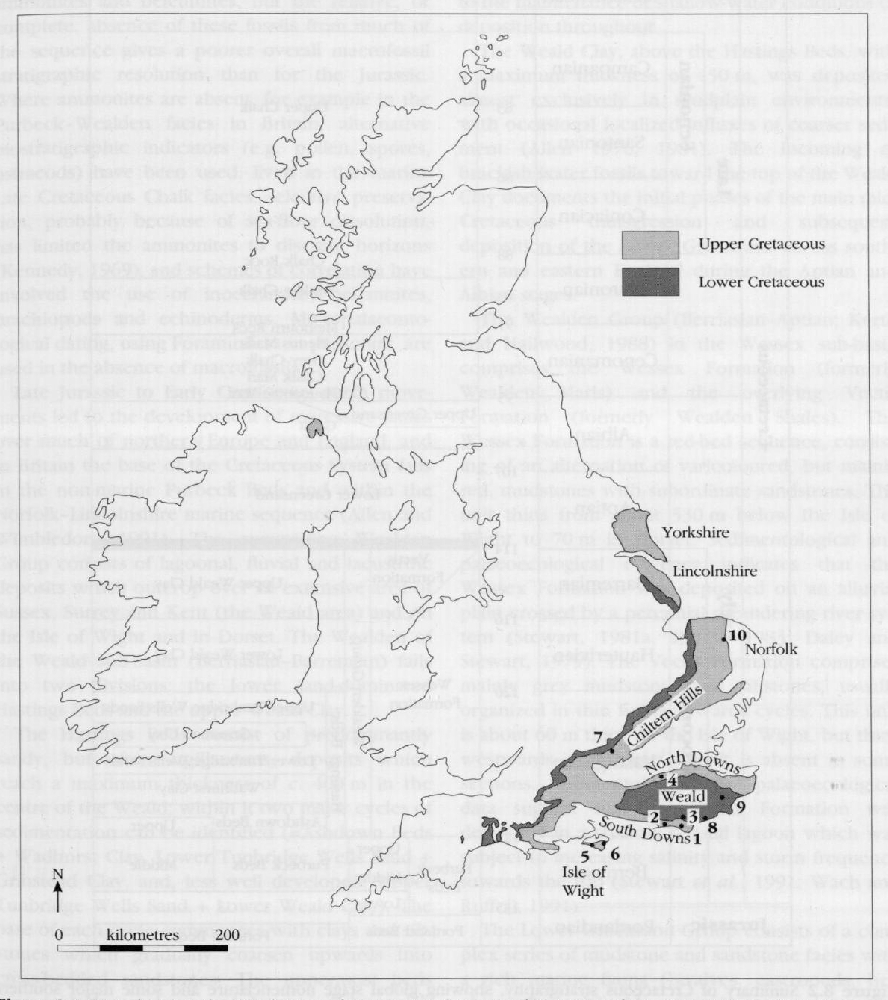

The Cretaceous System in Britain

The Cretaceous has been zoned on the basis of ammonites and belemnites, but the relative, or complete, absence of these fossils from much of the sequence gives a poorer overall macrofossil stratigraphic resolution than for the Jurassic. Where ammonites are absent, for example in the Purbeck-Wealden facies in Britain, alternative biostratigraphic indicators (e.g. pollen, spores, ostracods) have been used. Even in the marine Late Cretaceous Chalk facies, selective preservation, probably because of sea-floor dissolution, has limited the ammonites to discrete horizons (Kennedy, 1969), and schemes of correlation have involved the use of inoceramids, belemnites, brachiopods and echinoderms. Micropalaeontological dating, using Foraminifera in particular, are used in the absence of macrofossils.

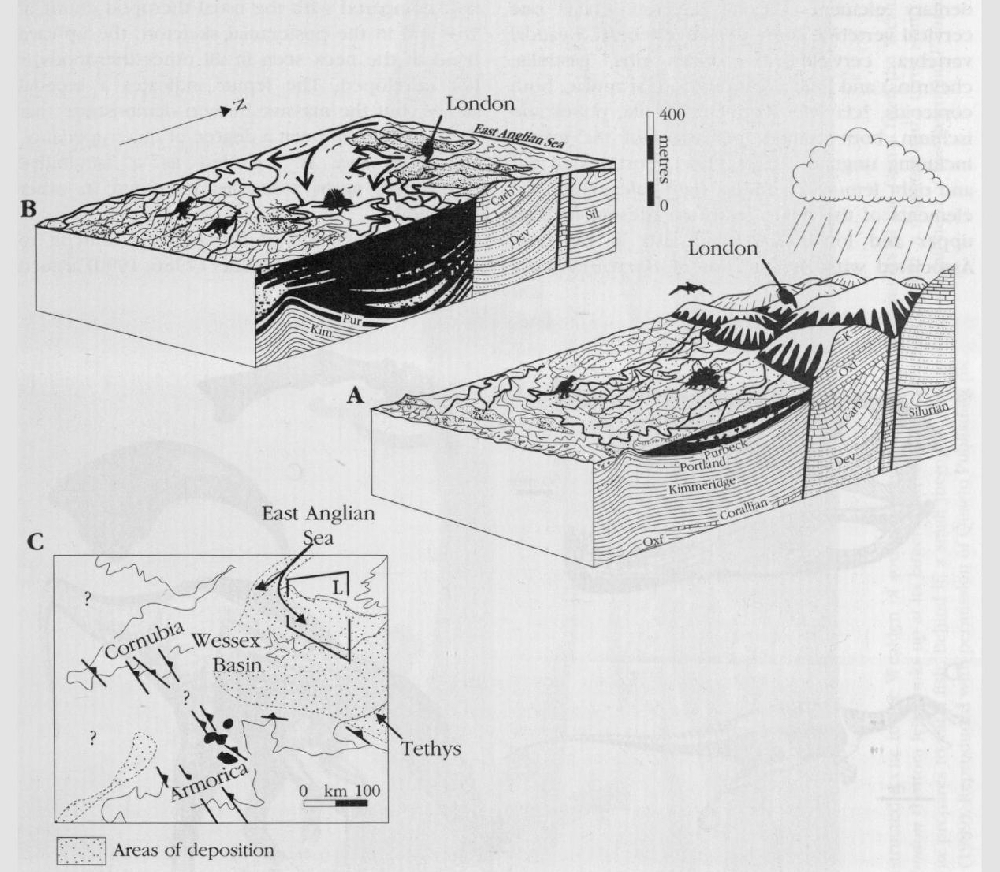

Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous earth movements led to the development of regressive facies over much of northern Europe and England, and in Britain the base of the Cretaceous System falls in the non-marine Purbeck Beds and within the Norfolk–Lincolnshire marine sequence (Allen and Wimbledon, 1991). The succeeding

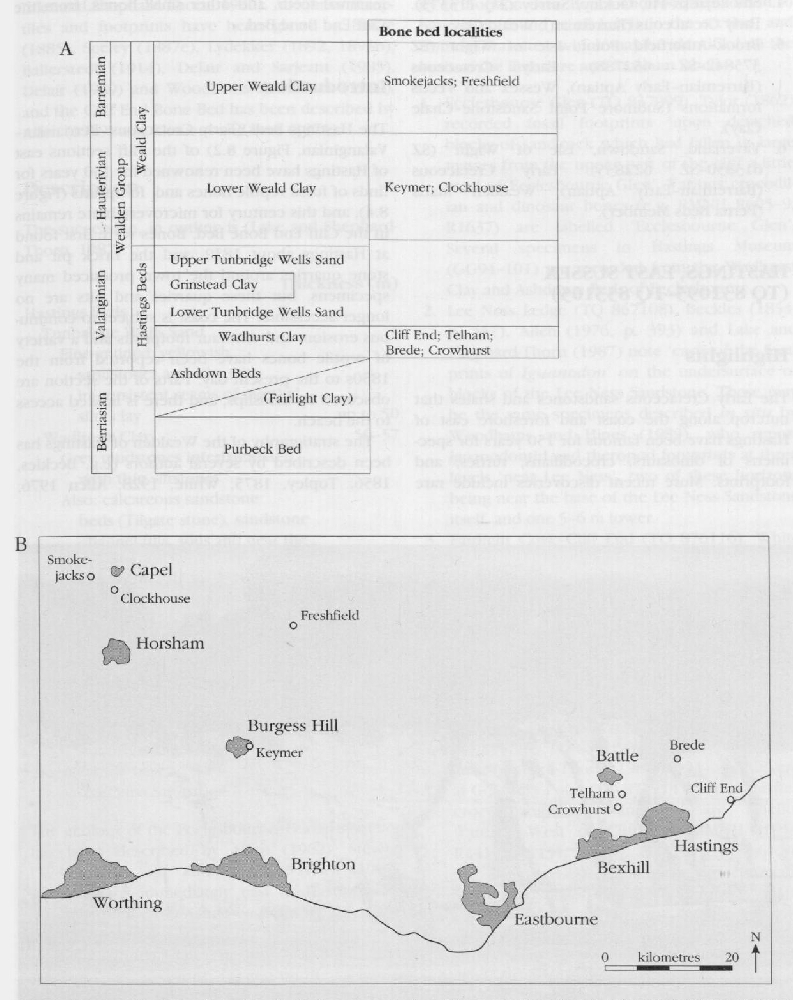

The Hastings Beds consist of predominantly sandy, but often argillaceous, deposits which reach a maximum thickness of c. 400 m in the centre of the Weald; within it two major cycles of sedimentation can be identified (=Ashdown Beds + Wadhurst Clay,

The Weald Clay, above the Hastings Beds, with a maximum thickness of 450 m, was deposited almost exclusively in mudplain environments, with occasional localized influxes of coarser sediment (Allen 1976, 1981). The incoming of brackish water fossils toward the top of the Weald Clay documents the initial phases of the main mid-Cretaceous transgression and subsequent deposition of the Lower Greensand across southern and eastern England during the Aptian and Albian stages.

The

The

Transgression, initiated in the Aptian, continued until near the close of the Cretaceous and brought changes in sedimentation which led to massive developments of coccolith ooze that now forms the Chalk. Subsequent sedimentation was occasionally interrupted when regressive phases led to deposition of 'nodular chalk' and associated hardgrounds.

At the end of the Cretaceous (late Maastrichtian) there was a substantial marine regression in Britain, and much of Europe. This coincided with a major phase of extinction that affected many groups of invertebrates and vertebrates; among marine invertebrates, the ammonites, belemnites, inoceramids and rudists became extinct.

Reptile evolution during the Cretaceous

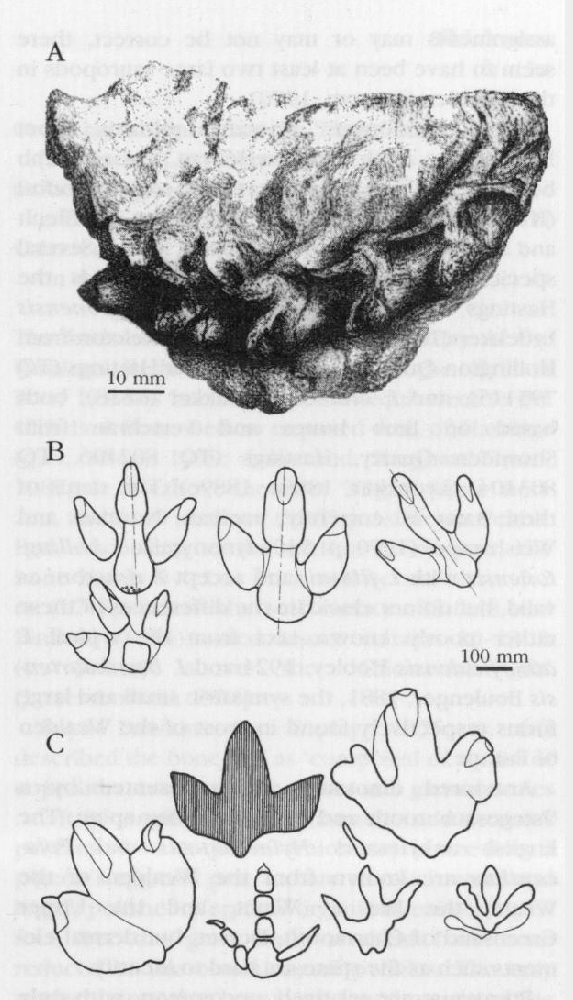

The Cretaceous Period is known for its highly diverse dinosaur faunas. In Britain the best represented forms are the ornithischians which occur abundantly in the

British records of Mid- and Late Cretaceous dinosaurs are less satisfactory because of the shift to marine sedimentation. Worldwide, however, dinosaurs showed major advances in the Late Cretaceous. New groups of ornithopods, particularly the duck-billed hadrosaurs, came to dominate terrestrial faunas and their relatives, the horned ceratopsians, also became diverse elsewhere. The sauropods were only patchily represented during Late Cretaceous times, and the stegosaurs had declined dramatically. Ankylosaurs witnessed a modest radiation, and carnivorous theropods, large (e.g. Tyrannosaurus rex) and medium-sized (e.g. Struthiomimus, Stenonychosaurus), are known from several parts of the world. Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas are best known from North America (the midwest states of Montana, the Dakotas, Colorado, Wyoming, Texas and the province of Alberta, as well as some eastern states) and Mongolia. Some significant Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas are also becoming better known from South America, India, China and Romania.

Among other terrestrial reptile groups, such as turtles, crocodilians, lizards and snakes, major evolutionary steps took place. The turtles diversified on land and in the sea, and many modern families appeared. Lizards also diversified on land, giving rise to many modern groups, as well as some extinct ones, most notable of which were the large marine mosasaurs and their relatives. In addition, snakes arose from 'lizards' during the Early Cretaceous, and some early constricting (non-poisonous) groups became established. Crocodilians diversified mainly on land and in fresh waters, while the marine metriorhynchids of the Jurassic declined. Many new crocodilian groups appeared, including the mammal-like terrestrial notosuchians, the giant sebecosuchians, both of these mainly in southern continents, and the modern eusuchians. Species of true crocodile and alligator are known from the Late Cretaceous.

In the air pterosaurs had become greatly advanced, and by the end of the Cretaceous occupied a variety of adaptive zones as highly efficient fish-eating soarers, as well as insectivorous forms using flapping flight. Cretaceous pterosaurs were all pterodactyloids, the advanced Glade, and their size was, on the whole, much larger than the sparrow- to seagull-sized Jurassic pterosaurs. British Cretaceous pterosaur records are patchy, and not comparable in quality with the finer Early Cretaceous forms from Brazil (Santana Formation) and Mongolia, or the forms from the marine Late Cretaceous of the mid-American seaway area (Kansas, Texas). These animals were accompanied by birds which had arisen from advanced theropod dinosaurs during the Late Jurassic. Birds have a very weak Cretaceous record, with good representation only of the Late Cretaceous coastal forms in Kansas and Texas, and little in Britain.

Marine reptiles show very considerable changes in the Cretaceous. Ichthyosaurs never again achieved the importance they had in the Jurassic, and remains are patchily distributed in many parts of the world through the period, with the last ones seemingly being Cenomanian in age. Plesiosaurs also dwindled in significance, although several groups, especially giant pliosaurs and long-necked elasmosaurs, lasted right to the end of the Cretaceous, and are represented especially in southern continents and in Texas. Cretaceous ichthyosaur and plesiosaur fossils are rare in Britain. The main Cretaceous marine group was the mosasaurs, giant marine lizards, which became top carnivores, possibly as a result of the decline of the pliosaurs. Mosasaurs are patchily represented in the British Chalk, although they are better known in the type Maastrichtian of the Netherlands and in Belgium, in the United States and in parts of north Africa. At the end of the period the mosasaurs, with the other large marine reptiles of the Jurassic and Cretaceous (e.g. ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs), which had started to decline earlier, also disappeared. The end-Cretaceous mass extinction event is best known, however, for the demise of the dinosaurs, although by very latest Cretaceous times the group seems to have been somewhat depleted both in numbers and diversity.

British Cretaceous reptile sites

British Cretaceous localities have provided good material of many typical reptile groups, particularly of ornithischian dinosaurs, which are known from several localities in the Early Cretaceous rocks of the Weald of Sussex, Surrey and Kent, and the Isle of Wight. Saurischian dinosaurs, the theropods and sauropods, are rare. Important finds of pterosaurs are known from the Gault of Folkestone, the Cambridge Greensand and also from the Middle Chalk where they are associated with well preserved remains of lizards, snakes and turtles. Terrestrial turtles and crocodilians are also known from the Wealden, and the Cambridge Greensand. The marine plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs are also represented in most of the sequence, and mosasaurs are known from a few localities in the Chalk.

The strength of the British Cretaceous record lies in the relatively well-dated and rich Early Cretaceous terrestrial faunas of the Wealden; this provides the richest and best view of Early Cretaceous vertebrates anywhere in the world. Some Mid- and Late Cretaceous faunas are good, but they represent mainly marine components of the reptilian faunas, and there are better faunas elsewhere. The British record is of no value in depicting Late Cretaceous terrestrial reptilian evolution.

Early Cretaceous: Wealden (Berriasian–Barremian)

The lagoonal, lacustrine and fluvial deposits of the

The Wealden of the Weald (Berriasian–Barremian) is well known for its fossil reptiles, and specimens have come from many localities, most of which are inland extractive sites and no longer accessible. Dinosaurs, crocodilians and pterosaurs are known from all Wealden formations, but they occur most frequently in the Hastings Beds. The succeeding Weald Clay has yielded fewer remains, but has recently produced the unusual theropod dinosaur Baryonyx. Well-recorded reptile sites include the following:

WEST SUSSEX: Loxwood (

EAST SUSSEX: Hamsey Brick Works (

Sites around Hastings are detailed in the Hastings report.

KENT: Brenchley (

SURREY: Harting Combe, near Haslemere ('Iguanodon' footprints; Delair and Sarjeant, 1985, p. 146); Clockhouse Brickworks (

In the Isle of Wight the Wealden beds are represented by predominantly argillaceous facies of the Wealden Marls and the Wealden Shales (Wessex and Vectis formations), which are seen best in coast sections between Brook and Atherfield Point on the south-west coast and at Yaverland on the south-east coast.

Outside the Wealden of the Weald and the Isle of Wight Early Cretaceous reptiles are known from the Spilsby Beds (Portlandian-Berriasian) of Spilsby, Lincolnshire

Six early Cretaceous GCR sites are selected

- Hastings, East Sussex

[TQ 831 095] –[TQ 853 105] . Early Cretaceous (Berriasian–Valanginian), Hastings Beds (Ashdown Beds, Tunbridge Wells Sand). - Black Horse Quarry, Telham, East Sussex

[TQ 769 142] . Early Cretaceous (Valanginian), Hastings Beds. - Hare Farm, Brede, East Sussex

[TQ 832 184] . Early Cretaceous (Valanginian), basal Wadhurst Clay. - Smokejacks Pit, Ockley, Surrey

[TQ 113 373] . Early Cretaceous (Barremian), Weald Clay. - Brook–Atherfield Point, Isle of Wight (

[SZ 375 842] –[SZ 452 788] ). Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Early Aptian), Wessex and Vectis formations (Sudmore Point Sandstone–Chale Clay). - Yaverland, Sandown, Isle of Wight (

[SZ 613 850] –[SZ 622 835] ). Early Cretaceous (Barremian-Early Aptian), Wealden Marls (Perna Beds Member).