Chapter 2 The Wessex Basin (Dorset and central Somerset)

M.J. Simms

Introduction

The Wessex Basin has seen more intensive research than any other single Lower Jurassic depocentre in Britain. This is largely on account of the exceptional exposure along the Dorset coast of virtually the entire Jurassic succession, but it perhaps also owes something to the fact that the exhumed periclines of the Mendip Hills, at the north-western edge of the basin, allow direct observation of the Palaeozoic basement structures that are believed to have controlled subsidence and uplift throughout the basin's history. Numerous papers have been published on various aspects of the basin, or parts of it (e.g. Stoneley, 1982; Chadwick et al., 1983; Whittaker, 1985; Chadwick, 1986; Lake and Karner, 1987; Jenkyns and Senior, 1991; Evans and Chadwick, 1994, to name but a few). There is also a substantial body of sub-surface data obtained from a large number of boreholes that have been drilled in the search for hydrocarbons (e.g. Sellwood et al., 1986; Ainsworth et al., 1998b) and from geophysical surveys that have been conducted across the area.

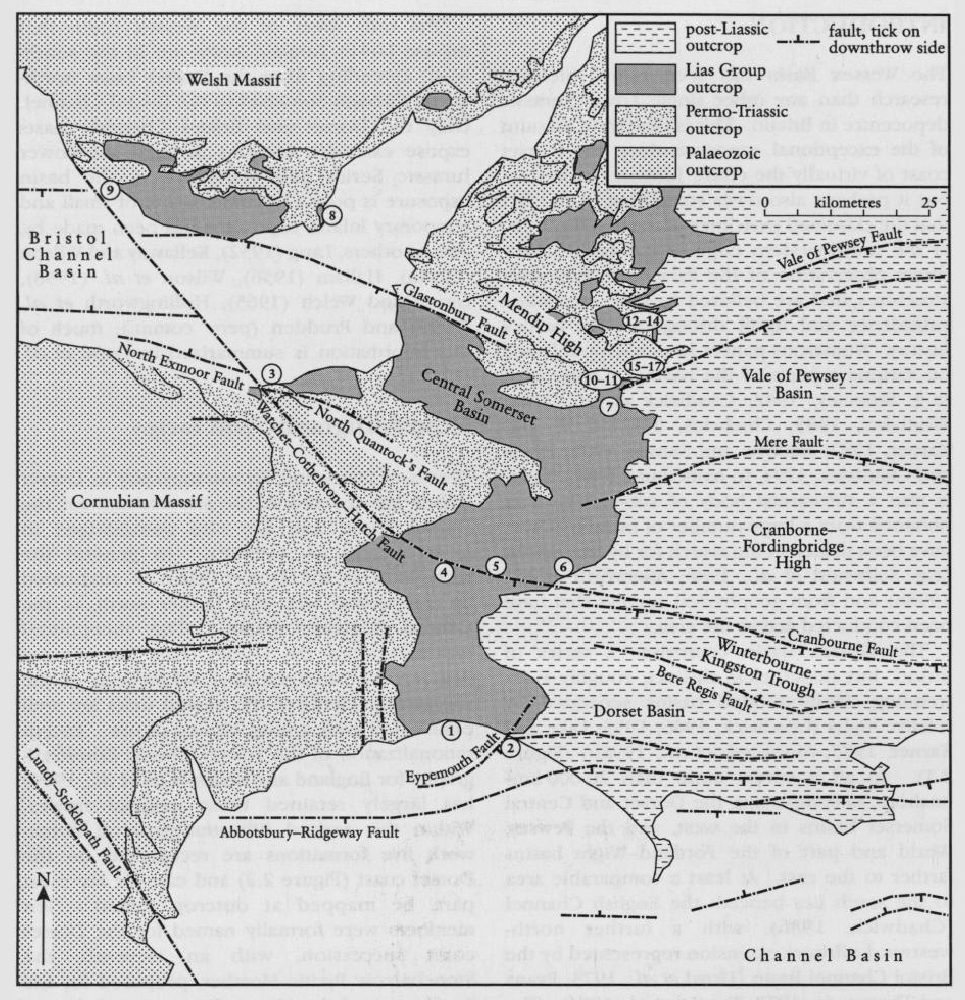

The Wessex Basin comprises a series of linked, but nonetheless distinct, roughly E–W-trending, fault-bounded basins separated by relative highs (Chadwick, 1986; 1993; Lake and Karner, 1987; Ainsworth et al., 1998b)

Within the basin the sedimentary fill, of Permian to Tertiary age, lies unconformably upon Lower Palaeozoic to Carboniferous rocks. Typically the fill is about 2 km thick though locally it may exceed 3 km.

The only areas of the Wessex Basin that expose Lower Jurassic strata are in the southwest, extending from the Dorset coast northwards through Somerset to the Bristol Channel. Only the Dorset and Bristol Channel coasts expose extensive sections through the Lower Jurassic Series and elsewhere in the basin exposure is poor. Documentation of small and temporary inland exposures has been made by, among others, Lang (1932), Kellaway and Wilson (1941a), Hallam (1956), Wilson et al. (1958), Green and Welch (1965), Hollingworth et al. (1990) and Prudden (pers. comm.); much of this information is summarized in Cope et al. (1980a).

Lithostratigraphy and facies

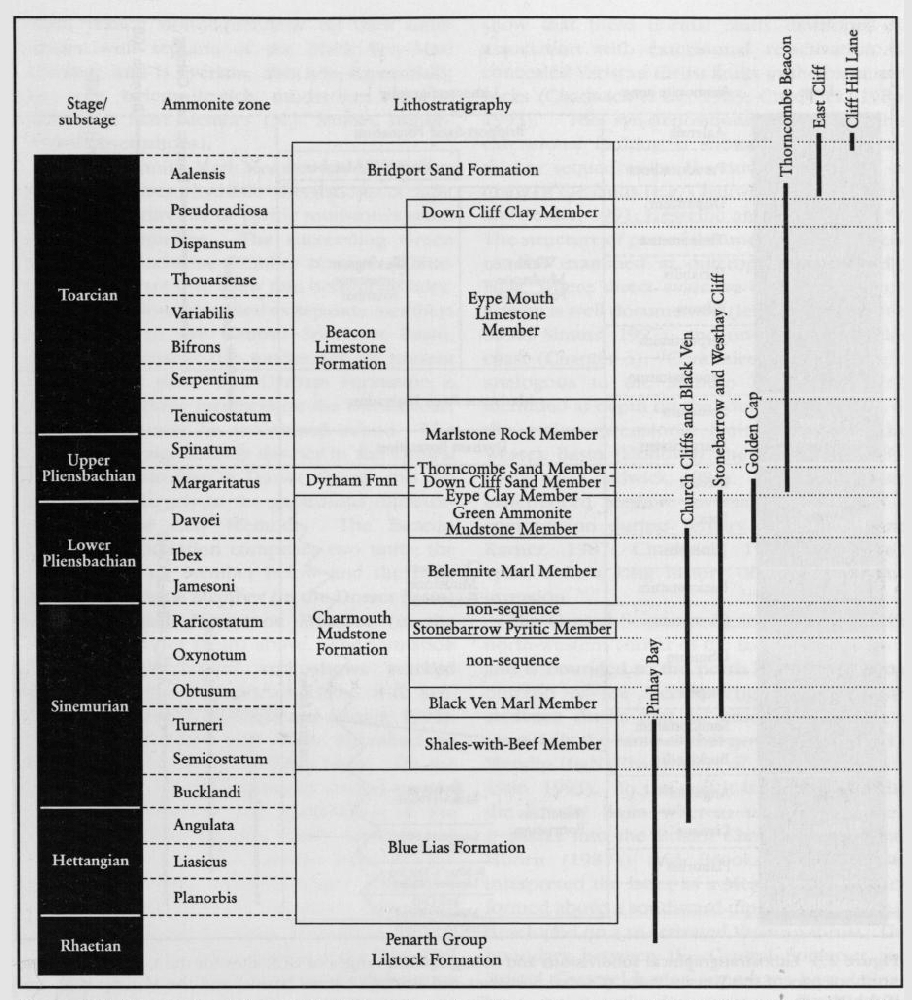

Details of facies and lithostratigraphy in Dorset largely are covered in the site account for the Dorset coast, and are also summarized in Ainsworth et al. (1998b). In general the succession in the Dorset Basin is attenuated by comparison with that farther north, in the Central Somerset Basin. The exceptional exposure along the Dorset coast has allowed detailed lithostratigraphical subdivision of the succession. Many of the named units are well established with a long history of use. Recent rationalization of the Lower Jurassic lithostratigraphy for England and Wales (Cox et al., 1999) has largely retained these original names. Within this revised lithostratigraphical framework five formations are recognized on the Dorset coast

The

The boundary between the two is essentially arbitrary but was drawn below a conspicuous limestone band, the Birchi Tabular (Bed 76a of Lang et al., 1923). In the Central Somerset Basin correlative strata are developed in similar facies to that seen on the Dorset coast, although there is little development of 'beef'. Separate members can be recognized only where distinctive marker beds are present, such as at Chard Junction where the Stellare Nodules near the top of the

The

Basin development

The 'Wessex Basin' is an inclusive term for a series of inter-connected E–W-orientated asymmetric grabens or half-grabens bounded by major faults or fault zones downthrowing mainly to the south

The Central Somerset Basin lies towards the north-western corner of the larger Wessex Basin and is bounded to the north by the Palaeozoic outcrop of the Mendip High. Geophysical evidence shows that its structure at depth is essentially the same as that now exposed on the Mendip High (Chadwick et al., 1983; Chadwick, 1986, 1993). To the east it is continuous with the Pewsey Basin whereas to the north-west it passes into the Bristol Channel Basin. Van Hoorn (1987a) and Brooks et al. (1988) interpreted the latter as a Mesozoic half-graben formed above a southward-dipping normal fault developed on a re-activated Variscan thrust. The boundary between the Central Somerset and Bristol Channel basins is perhaps best defined by a major strike-slip structure,' the Watchet–Cothelstone–Hatch Fault System. The Central Somerset and Dorset basins are separated by the westward extension of the Cranbome-Fordingbridge High

The Dorset, Central Somerset and Bristol Channel basins probably formed during the Permian Period, with the Watchet–Cothelstone–Hatch Fault System acting as a zone of transfer between southern and northern, possibly syn-orogenic, extension. The east–west strike of the basement thrusts is reflected in the east–west orientation of the Bristol Channel Basin and the Mendip and Cranbourne–Fordingbridge highs, while the NW-trending faults, which together comprise the Watchet–Cothelstone–Hatch Fault System, represent lateral ramps to these thrusts.

Comparison with other areas

Because of the long history of investigation of the Lower Jurassic succession on the Dorset coast, the sequence there is often taken as the 'standard' against which correlative successions elsewhere are compared. The lithostratigraphy of the Wessex Basin shows greater contrasts with the more distant basins, such as those of Cleveland and the Hebrides, than with those of the nearby Severn Basin and East Midlands Shelf. In a comparison of the Wessex and Cleveland basins, Hesselbo and Jenkyns (1995) concluded that the large-scale facies differences between the two reflected the more proximal (to land) setting of the Cleveland Basin. The same interpretation can probably be applied to the Hebrides Basin. The most obvious significant difference between the Wessex Basin succession and those elsewhere occurs in the Toarcian Stage, where dark laminated mudstones, which are present across most of Britain and mainland Europe, are represented by the highly condensed

The distribution of faunal elements through the Lower Jurassic succession of the Wessex Basin typically reflects either their biostratigraphical range (vertical distribution) or facies control (lateral distribution). Provincialism has been documented among two invertebrate groups in particular. In the Upper Pliensbachian Stage Ager's (1956a) work on brachiopods distinguished a South-western Province (the Wessex and Severn basins) from three others farther north. Within this province he recognized distinct Bridport and Ilminster sub-provinces, which effectively correspond to the Dorset and Central Somerset basins, and a Gloucester Subprovince corresponding to the Severn Basin, that was transitional to the Midland Province farther north. Howarth (1958) noted a close correlation between the brachiopod provinces recognized by Ager (1956a) and the distribution of species of the ammonite genus Pleuroceras. Both authors noted a profound difference in faunal composition between the South-western and Yorkshire provinces that they attributed to physical barriers to migration of the various taxa.