Show interactive timeline

11 Aonach Beag And Geal-charn

[NN 454 735]–[NN 470 747] and [NN 475 761]–[NN 497 746]

S. Robertson, J.R. Mendum and A.G. Leslie

Published in: The Dalradian rocks of the northern Grampian Highlands of Scotland PGA 124 (1–2) 2013 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pgeola.2012.07.010 Also on: NORA

11.1 Introduction

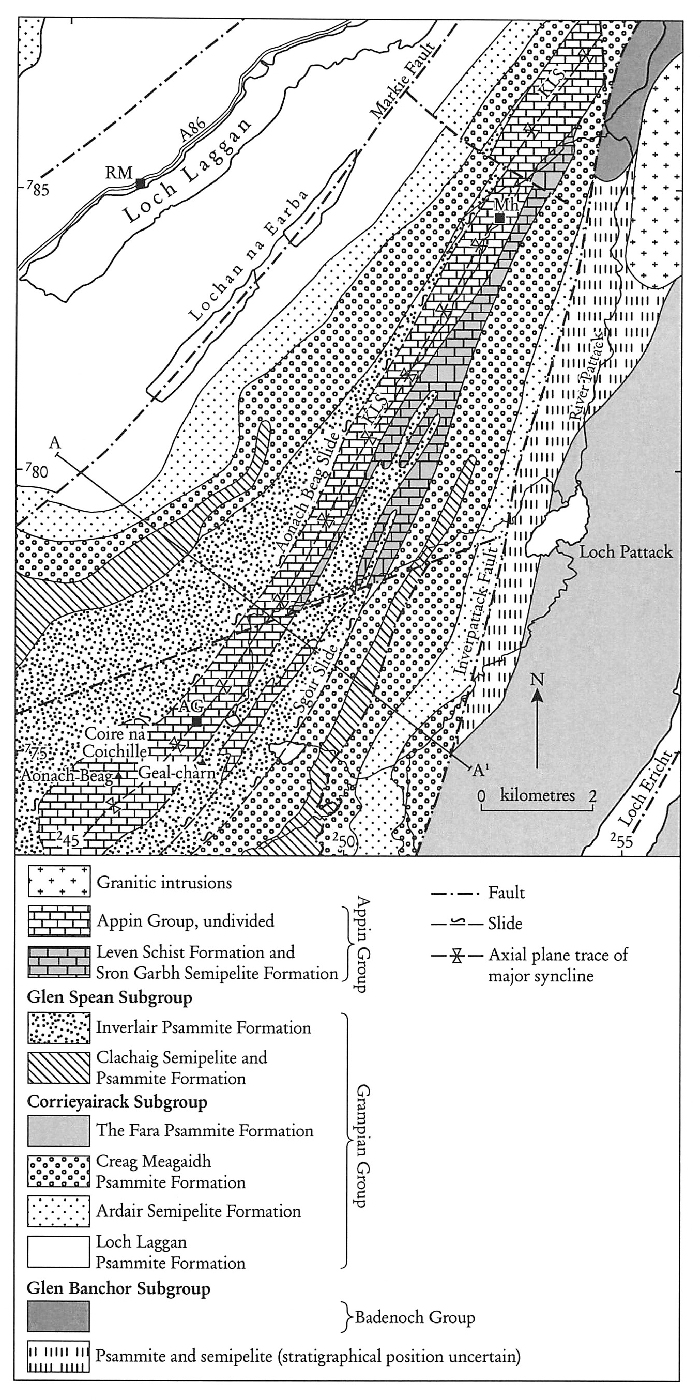

The Aonach Beag and Geal-charn GCR site provides one of the best cross-sections through the zone of sheared and tightly folded, steeply dipping metasedimentary rocks termed the Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt. Exposures around Aonach Beag [NN 457 743] and in the NE-facing corries of Coire Cheap [NN 476 754] and Coire Sgòir [NN 487 747] provide an excellent near three-dimensional section across this complex zone. The site includes a number of spectacularly developed ductile shear-zones or slides and associated isoclinal folds, elegantly first described by Thomas (1979). The stratigraphy, structure and metamorphism of the area have been most recently re-assessed by Robertson and Smith (1999), and details are incorporated within the BGS 1:50 000 Sheet 63E (Dalwhinnie, 2002), this report draws extensively upon that work.

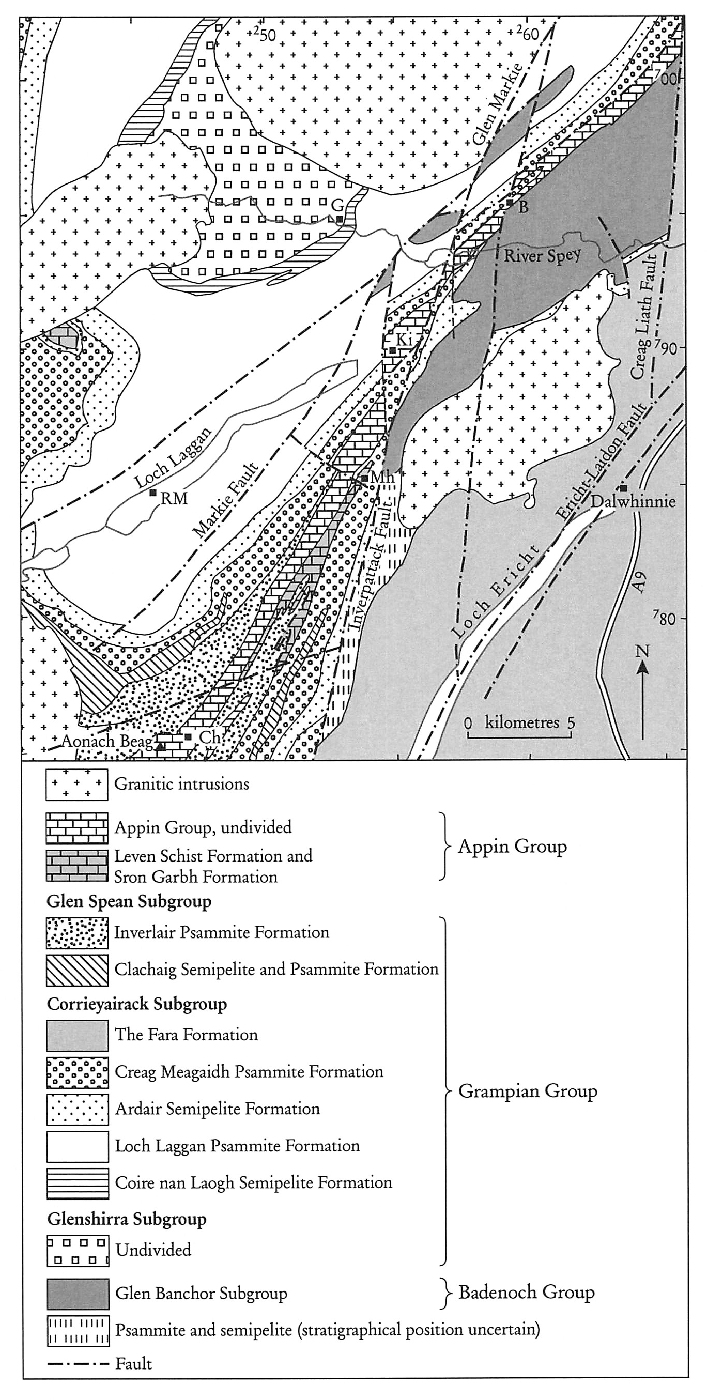

The Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt comprises a narrow zone of steeply dipping rocks that can be traced north-eastwards for more than 50 km from Aonach Beag (Figure 5.18) and (Figure 5.30). A varied association of lithologies, including metacarbonate rock, kyanite-bearing pelite and semipelite, quartzite and the Kinlochlaggan Boulder Bed, occur in the core of the steep belt and are collectively referred to as the Kinlochlaggan succession in the Appin Group (Robertson and Smith, 1999). These lithologies contrast markedly with the surrounding psammites and semipelites of the Grampian Group.

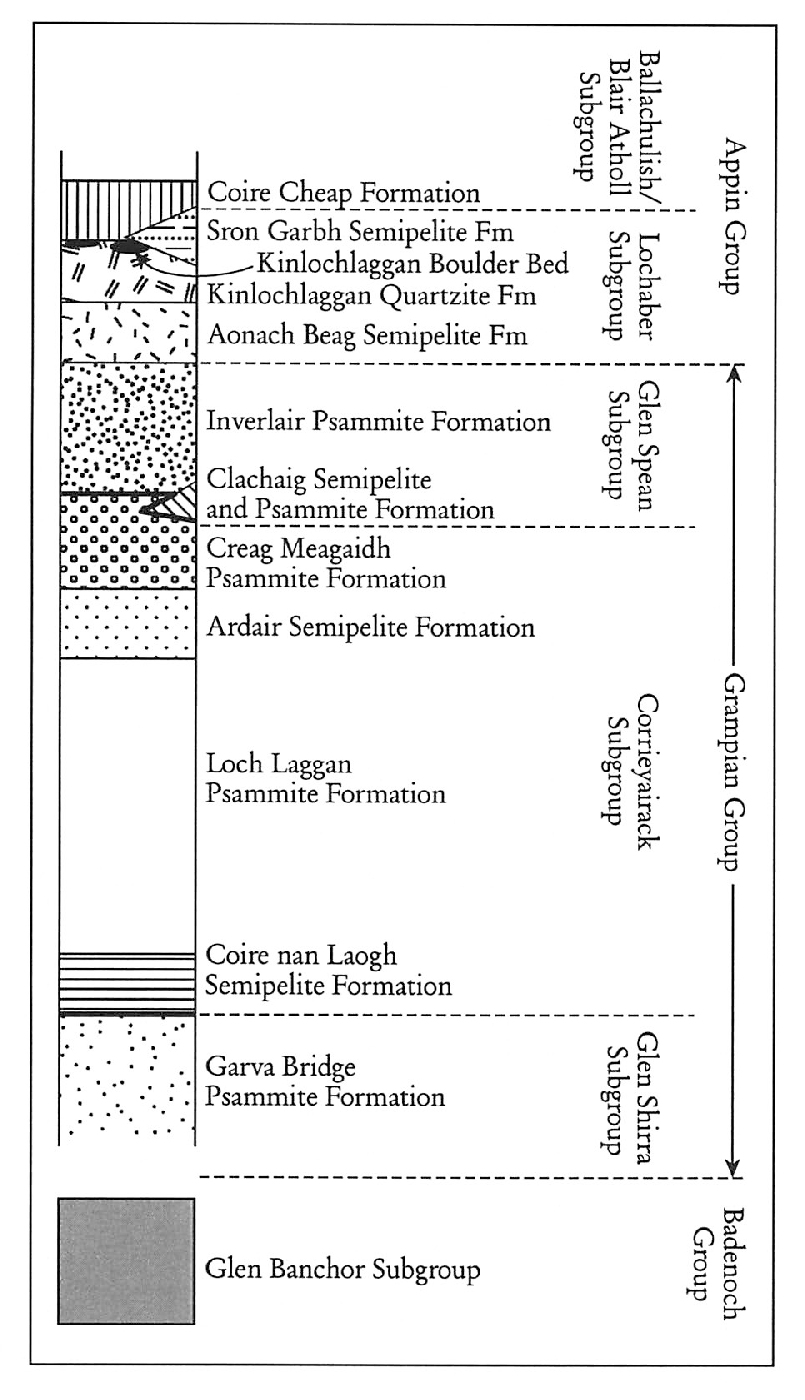

To the west of the steep belt, in the Loch Laggan-Glen Roy area, the Grampian Group succession is at least 8 km thick (Key et al., 1997). There the sand- and silt-dominated succession is divided into three subgroups, which broadly reflect their depositional environment; the fluvial and shallow marine Glenshirra Subgroup is overlain by deeper water sediments of the Corrieyairack Subgroup that were deposited largely from turbidity currents. These are overlain in turn by the shallow marine to estuarine Glen Spean Subgroup in a basin-shoaling succession. The overlying Appin Group represents an overall transgressive system with a silt- and mud-dominated succession contrasting with the mainly sandy Glen Spean Subgroup.

To the south-east of the steep belt, much of the Grampian Group is assigned to the Fara Psammite Formation of the Strathtummel succession. It is less well known than the succession of the Loch Laggan–Glen Roy area, although it was described by Thomas (1979, 1980). Robertson and Smith (1999) made only tentative correlations with the Corrieyairack Subgroup. Gneissose rocks of the Glen Banchor Subgroup, which are thought to form a basement to the Grampian Group (Robertson and Smith, 1999), extend partway along the south-east side of the steep belt from the north-east to within 12 km of this GCR site. They are exposed on the eastern side of the Allt Mhainisteir GCR site.

11.2 Description

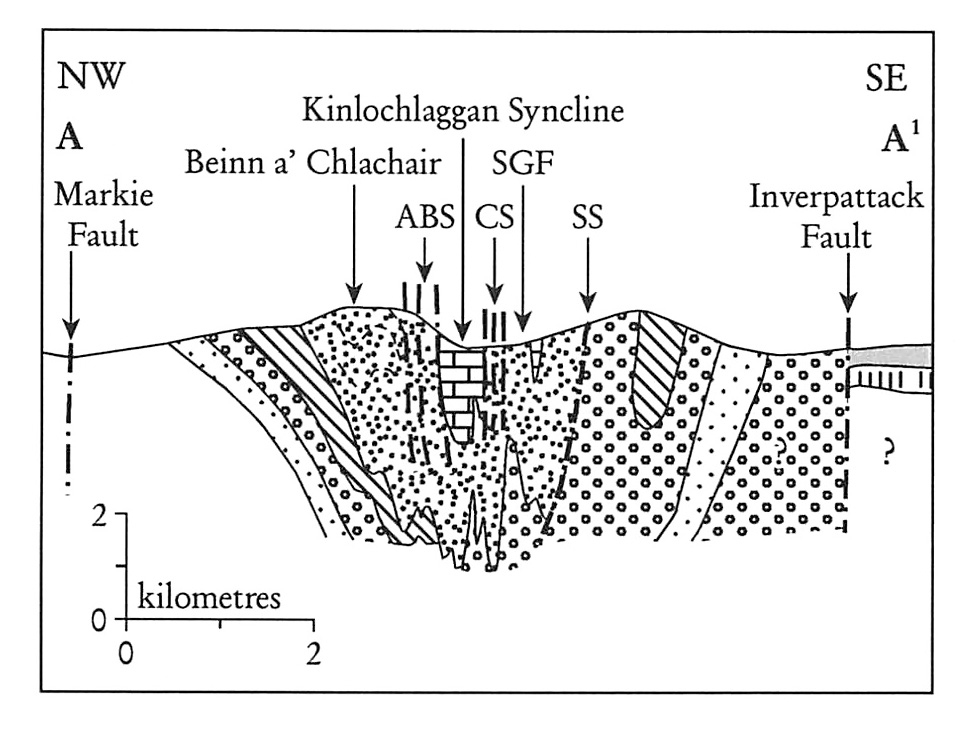

The site is remote and mountainous. Aonach Beag (1116 m) and Geal-charn (1107 m) form a dramatic ridge to the north-west of the Ben Alder massif. Coire Cheap and Coire Sgòir both face north-east along the continuation of that ridge (Figure 5.32). A lithostratigraphical column for the area within and west of the steep belt is shown in (Figure 5.27). Within the GCR site, Grampian Group rocks form the flanks of the steep belt whereas the Appin Group rocks occupy the core in the Kinlochlaggan Syncline and related folds. The broad disposition of these lithologies is illustrated in the cross-section (Figure 5.31).

11.2.1 Structural setting of the steep belt

The Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt is defined as a zone of steeply inclined rocks (dips of over 60°) up to 4 km wide (Robertson and Smith, 1999). The overall attitude of lithological layering, the axial surfaces of isoclinal folds and associated tectonic fabrics are approximately coplanar.

The Grampian Group in the Loch Laggan area, north-west of the steep belt, has an apparently simple structural history. Strata in the Loch Laggan-Glen Roy area are generally moderately to steeply inclined, with a preponderance of upright early structures (Key et al., 1997). An early schistosity, steeper than bedding, occurs in semipelitic rocks and in the micaceous tops to graded beds. This is modified in places by a steeply inclined crenulation. Minor folds are rare and strain is generally low, as is indicated by the widespread preservation of sedimentary structures (e.g. Glover et al., 1995).

The structural history is more varied to the south-east of the steep belt. A large area of gently inclined, albeit strongly flattened, rocks with recumbent early folds, extends for several tens of kilometres east of Kinloch Laggan to beyond Dalwhinnie (Robertson and Smith, 1999). In this area, the Glen Banchor Subgroup of the Badenoch Group preserves a protracted tectonothermal history in which an early gneissose foliation is deformed by at least one generation of isoclinal folds. That early gneissose foliation is deformed by shear-zones with associated syntectonic veins of quartz and quartzofeldspathic pegmatite yielding Rb-Sr muscovite ages of c. 750 Ma (Piasecki and van Breemen, 1983). In contrast, much of the adjacent eastern outcrop of Grampian Group strata shows evidence of only a relatively simple history. A single bedding-parallel schistosity is pervasive and is the result of strong flattening strain. Small-scale recumbent and asymmetrical folds are rare over a large area of the Grampian Group outcrop between the steep belt and the A9 road section north of Drumochter and no large-scale folds have been recognized to date. An upright open crenulation is developed locally. In contrast, Thomas (1979) recorded that the Ben Alder area preserves evidence of major changes in facing of early recumbent structures south-east of the Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt (see the Ben Alder GCR site report). The model proposed by Thomas (1979) has early SE-facing nappe structures refolded by two further phases of folding, with the major nappes divergent from the upward-facing steep belt.

The steep belt separates these contrasting north-western and south-eastern structural domains (Figure 5.31). A progressive increase in inclination of strata into the steep belt from the north-west culminates in a zone, mostly less than 2 km wide, where inclination is over 75°. The south-eastern margin of the steep belt is more abrupt with steeply inclined and near flat-lying rocks closely juxtaposed.

The intensity and complexity of deformation within the steep belt is striking when compared with patterns to the north-west and south-east. Robertson and Smith (1999) recognized three main phases of deformation in the steep belt, which broadly equate with those described by Thomas (1979). The first phase produced large-scale tight to isoclinal folds with amplitudes of several kilometres and a penetrative axial planar schistosity. This deformation resulted in extreme attenuation of fold limbs and the development of slides. Adjacent to the slides, there is a marked decrease in the wavelength and increase in frequency of tight to isoclinal folds with minor dislocations on some fold limbs (see also the Allt Mhainisteir GCR site report). The main dislocations are generally marked by zones with intense platy fabrics, varying in width from about a metre up to 20 m. Both small- and large-scale dislocations generally show excision of strata with only rare repetition.

The first phase structures were modified and attenuated during a second phase of close to isoclinal folding. In the north, the first and second phase structures are co-axial and coplanar and therefore difficult to distinguish but in the southern part of the steep belt (e.g. around this GCR site), the second deformation is less intense and is oblique to the first phase. Thus, interference structures are widely developed and in psammites a coarse secondary biotite foliation is commonly discordant to the first fabric. Re-activation of some of the slide-zones is indicated by intensification of the second fabric, which is rotated into parallelism with the first. Elsewhere, the slide-zones are clearly cut by the coarsely spaced biotite fabric. Kyanite-grade metamorphism developed during the second phase of deformation. Later in this phase, fluid movements along the sheared and deformed zones of high strain resulted in local sillimanite replacement of kyanite (Phillips et al., 1999).

The overall geometry of the steep belt is that of a major upright synform (Figure 5.31). The facing and vergence of small- and medium-scale structures indicates that much of the structural pattern developed during second-phase tightening and intensification of earlier first-phase structures. Few significant changes in the large-scale pattern of fold vergence occurred during the second phase and primary facing relationships were largely preserved from the onset of deformation in the steep belt. The most important major fold structure, the Kinlochlaggan Syncline, constrains the main outcrop of the Kinlochlaggan succession to a zone generally less than 1 km wide. Critical exposure of the fold hinge can be traced in detail on the south-west ridge of Aonach Beag [NN 454 735] (Figure 5.30). The Aonach Beag Slide lies on the western limb of the syncline (Thomas, 1979). This important dislocation has the same lateral extent as the main syncline and defines the north-western limit of the Kinlochlaggan succession. South-east of the trace of the main syncline, the Cheap slides separate the Kinlochlaggan Syncline from the Sron Garbh anticlinal fold-complex and associated slides to the east (Figure 5.30). The Kinlochlaggan succession is also present within parts of this latter fold complex, the eastern limit of which is defined by the Sgòir Slide, which was first recognized as separating contrasting stratigraphical successions by Thomas (1979). The Cheap and Sgòir slides die out gradually farther to the north-east.

The second phase folds are refolded by sporadically developed third phase structures. These occur primarily close to the eastern edge of the steep belt, although they are also prominent around Aonach Beag [NN 458 742] where they have nucleated on the earlier folds. Open to close SE-verging folds are typical, with axial planes inclined moderately or steeply to the east-south-east. Crenulation cleavages are developed in semipelite but are generally confined to fold hinges. The absence of penetrative fabrics, even in the tightest folds, and of new metamorphic mineral growth or recrystallization, readily distinguishes the third phase structures.

11.2.2 Grampian Group lithostratigraphy

Within this GCR site, the units of the Grampian Group range from near-undeformed sequences with well-preserved sedimentary structures to migmatitic gneissose and highly sheared equivalents. The stratigraphy is summarized in (Figure 5.27).

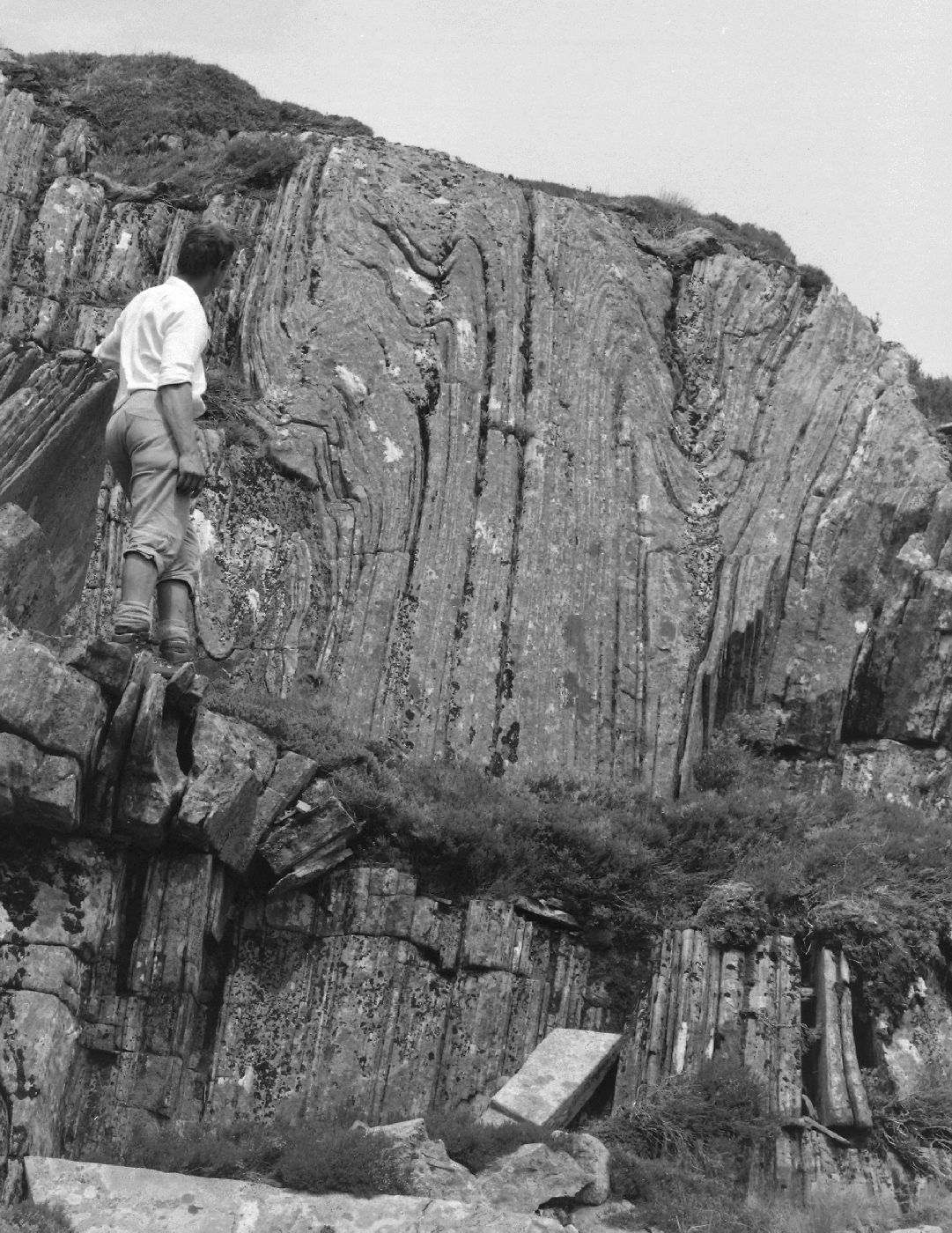

The Creag Meagaidh Psammite Formation comprises thin- to medium-bedded psammite and micaceous psammite with little lithological variation; the field appearance is largely controlled by the degree of strain. On the cliffs of Sgòr Iutharn [NN 490 744], the formation is generally preserved in a low-strain state (Figure 5.32). Beds are typically 10 to 15 cm thick and are rarely 25 to 30 cm. These mostly comprise grey to white, rather massive feldspathic psammite that grades into thin (mostly less than 3 cm) micaceous psammite, semipelite or even pelite. The local presence of sharp bases and gradations in the tops of the beds into more-micaceous lithologies is considered to reflect primary graded bedding. Differential erosion across these graded units produces distinctive ‘sharks teeth’ profiles with preferential weathering inwards of the more-micaceous tops. High-strain areas are very flaggy to fissile with fine-scale (several millimetres) interbanding of platy psammite and micaceous psammite.

The Creag Meagaidh Formation is overlain stratigraphically by the Clachaig Semipelite and Psammite Formation and in places by the Inverlair Psammite Formation. The boundary with the latter is tectonic (the Sgòir slides)–see below.

The Clachaig Semipelite and Psammite Formation comprises a varied succession dominated by semipelite. On the north-east ridge of Sgòr Iutharn, the Lancet Edge [NN 495 746], the Clachaig Formation forms the core of an isoclinal syncline (?F1) on the eastern edge of the steep belt. Here there is a transitional contact with the underlying psammite of the Creag Meagaidh Formation. The basal part of the Clachaig Formation is a massive, coarsely foliated, garnetiferous biotite-rich semipelite and pelite with minor thin beds of micaceous psammite. Higher in the succession, quartzose and feldspathic psammite beds are seen within thin- to medium-bedded semipelite, micaceous psammite and feldspathic psammite. Spectacular minor folds and refolded folds are present. Minor calcsilicate-rock lenses occur in these lithologies.

The Inverlair Psammite Formation is particularly well seen around Coire Cheap (Figure 5.30) in massive exposures showing transitions from psammite to micaceous psammite on scales ranging from a few centimetres to a metre or so (e.g. around [NN 478 755]). Micaceous psammite beds are typically only a few centimetres thick. Boundaries are commonly subtle as a result of extensive recrystallization and grain coarsening, a characteristic feature of this formation. The formation is generally gneissose, particularly the micaceous psammites, which carry a coarsely spaced fabric within leucosomes that are pegmatitic in places.

On the north-west side of the steep belt, the degree of gneissification and deformation increases towards the Aonach Beag Slide and related ductile dislocation structures (Figure 5.30). The psammite is correspondingly more massive and gneissose with interbanded quartzite units in places. The slide-zone is marked by lithologies from the Inverlair Psammite Formation and Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation interleaved in an imbricate zone. Immediately north of a small col on the north-north-west ridge of Aonach Beag at [NN 452 751], notably striped migmatitic psammite and subsidiary semipelite show abundant segregation veins, tight folding and a gently ENE-plunging quartz-rodding lineation. These rocks lie within a slide-zone structurally just below the main Aonach Beag Slide that is exposed on the ridge.

Folded gneissose, and locally migmatitic, psammites and minor semipelites of the Inverlair Psammite Formation also occur extensively in the north-western part of Coire Sgòir [NN 485 750], east of the Kinlochlaggan succession in the core of the steep belt. The sequence is tightly folded and is cut by several ductile slide-zones (the Sgòir slides, (Figure 5.31)); slivers of the Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation (including amphibolite) occur in this high-strain zone. Contacts with folded and locally sheared psammite of the Clachaig, Creag Meagaidh and Aonach Beag formations are all steeply inclined ductile slides. Units of foliated gneissose semipelite, quartzite and quartzose psammite also occur locally.

11.2.3 Appin Group lithostratigraphy

Within the steep belt, the boundary of Grampian Group rocks with those of the overlying Appin Group is generally tectonic and is marked by platy zones of interbanded psammite and quartzite. These are seen spectacularly at [NN 477 756] in Coire Cheap (the Cheap slides). However, transitional stratigraphical boundaries are also preserved in Coire Cheap to the west of Aisre Ghobhainn [NN 478 753] and locally north-west of Aonach Beag [NN 45 74]. At the former locality, psammite and gneissose micaceous psammite pass into platy micaceous psammite with quartz segregations and then schistose semipelite and micaceous psammite of the Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation.

The Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation is well developed on the north-west ridge of Aonach Beag [NN 457 743] and in Coire Cheap [NN 478 752], where the transitional boundary with the Grampian Group Inverlair Psammite Formation reveals the lowest parts of the formation. The formation dominantly comprises semipelite but contains progressively more psammite in its upper part. Units of tremolitic rock and thin white quartzites occur in the lower part. Abundant amphibolite sheets generally lie parallel to bedding but are discordant locally. These range from 15 cm to several metres thick, and are generally thicker adjacent to the overlying Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation and to thicker psammite units.

The Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation comprises massive white quartzite with large, locally prominent, white to pink feldspar crystals. Partings in the quartzite, which probably reflect bedding, are typically 5 to 60 cm apart and are controlled locally by micaceous psammite layers up to 2 cm thick. The feldspars are up to 5 mm long and are either scattered or are concentrated within layers, indicating a clastic origin. The formation has an outcrop width of between 5 and 160 m, a range that probably reflects both tectonic attenuation and original variation in depositional thickness. South-west of Aonach Beag [NN 455 740], in the hinge-zone of the Kinlochlaggan Syncline, the quartzite is 100 to 120 m thick, is well exposed in clean crags and exhibits only minor deformation. Pink feldspar clasts are scattered throughout individual white to pale-grey packets of dominantly quartz sand 1 to 20 cm thick. Minor coarser grained bases to these units are seen and in places more-micaceous tops are present. Grading shows that the formation youngs and faces upwards. No cross-bedding has been recorded here. However, minor cross-bedding and small-scale slump folds can be seen in the craggy exposures on the north-west ridge of Geal-charn at [NN 4715 7563] and in exposures farther north-east at [NN 4798 7667]. In the central part of the steep belt, to the west of Coire Cheap [NN 475 750], outcrop of the formation is repeated up to three times by upright isoclinal folding. Pebbly layers, 1 to 10 cm thick with rounded quartz and feldspar pebbles up to 6 mm across, occur in the quartzite in Coire Cheap at [NN 474 753]. Amphibolites, typically up to 2 m thick, are widespread and are commonly concentrated at the margins of the formation; examples in Coire Cheap and south-west of Aonach Beag are locally discordant and are clearly dykes.

The Kinlochlaggan Boulder Bed (see also the Kinlochlaggan Road GCR site report) is represented on the west wall of Coire Cheap [NN 4776 7566], by massive grey psammite containing scattered granite clasts up to 5 cm across and with a few discontinuous slightly micaceous layers. This occurrence has a gradational boundary over 20 or 30 cm with the underlying quartzite, is approximately 2 m thick and forms a lens about 20 m long. The lensoid nature is considered to be representative of the other occurrences in the region, thereby accounting for the discontinuous nature of the ‘boulder bed’.

To the west of and stratigraphically upwards from the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation in Coire Cheap, a 20 m-thick mixed unit of metacarbonate rock, calcsilicate rock, micaceous psammite and garnet amphibolite represents an attenuated Coire Cheap Formation. This is succeeded by a c. 100 m-thick semipelite unit forming the prominent peak of Sron Gharbh [NN 473 754]. The semipelite is characteristically dark grey, homogeneous and generally schistose, with widespread scattered small garnets; quartzofeldspathic segregations are rare whereas quartz segregations are widespread. This semipelite is not recognized 1 km to the north-east in the Allt Coire Cheap section but can be traced south-westwards into Coire na Coichille [NN 469 750] where it apparently lenses out; it is apparently a local facies development (Robertson and Smith, 1999). Kyanite-bearing semipelite occurs at the western boundary of the semipelite in Coire Cheap, and is succeeded to the west (at [NN 4754 7588]) by 16 m of flaggy, platy, very fine-grained, grey micaceous psammite.

This platy psammite marks the return to a heterogeneous succession of semipelite, calcsilicate rock and metacarbonate rock, all cut by amphibolite sheets, which extends north-eastwards from Aonach Beag [NN 455 740] through superb exposures in Coire Cheap and Allt Coire Cheap, the type area for the Coire Cheap Formation. The semipelitic units are gneissose and/or kyanite-rich in parts and locally they are graphitic. In Coire Cheap, the micaceous psammite referred to above is succeeded to the west by fine-grained platy micaceous psammite with thin quartzite ribs interbanded with thin layers (up to 1 m) of calcsilicate rock and metacarbonate rock. Lines of solution hollows up to a few metres deep, along with some resurgence and limited along-strike exposures might represent unexposed metacarbonate rocks. Locally (e.g. at [NN 4740 7571]), rusty-weathering micaceous psammite is cut by discordant amphibolite sheets up to 3 m thick. The discordance with schistosity in the micaceous psammite is up to 30° and the amphibolite is unfoliated. Rather fine-grained margins could reflect original chills, whereas relics of ophitic texture and blue-green amphibole are preserved in the central parts of the sheets. At [NN 4717 7541], graphitic schist with partially replaced kyanite occurs in loose blocks; contacts with adjacent lithologies are not exposed.

In the west wall of the corrie [NN 473 755], the graphitic schist is succeeded by c. 45 m of thinly bedded, cream- to buff-weathering metacarbonate rock, referred to as the Coire Cheap Limestone. The metacarbonate rock appears particularly thick here; no major fold closures have been identified but there are tight internal minor folds. A few amphibolite sheets and pods up to 2 to 3 m across occur, mostly near the western boundary. Farther west the metacarbonate rock is succeeded by c. 5 m of platy calcsilicate rock with thin beds of metacarbonate rock and then by a 50-70 m-thick gneissose kyanite semipelite referred to as the Coire Cheap Kyanite Gneiss. Kyanite is abundant throughout this unit and commonly comprises some 25% of the rock. Much of the kyanite is coarse (over 1 cm and rarely up to 5 cm long) and although many crystals are randomly arranged, some show subhorizontal alignment on the steep schistosity surfaces. A few garnet amphibolite layers up to 30 cm thick are present. The kyanite gneiss is succeeded to the north-west by a thin metacarbonate-rock layer in the corrie wall and then by approximately 20 m or so of rusty-weathering micaceous psammite with some layers of semipelite. The latter contain tourmaline and relics of kyanite largely replaced by muscovite. This is succeeded in turn in the corrie wall by several metres of calcsilicate rock, which is in contact to the west with the Kinlochlaggan Boulder Bed and the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation. The repetition of the underlying Kinlochlaggan Quartzite indicates that the trace of the Kinlochlaggan Syncline is crossed in Coire Cheap; the most likely place for the closure is in either the semipelite unit on Sron Garbh or in the Coire Cheap Limestone, although there is no obvious repetiton of the surrounding lithologies. This indicates either original facies changes or structural dislocation preferentially on one limb of the structure. Facies changes over short distances seem more likely given the significant lateral changes in the succession within a kilometre as indicated by the succession in the Allt Coire Cheap and to the south-west in Coire na Coichille.

11.3 Interpretation

11.3.1 Stratigraphical relationships

The Kinlochlaggan succession has generally been interpreted as an upward-facing succession within the core of the Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt, with the Grampian-Appin group boundary modified locally by sliding (Hinxman et al., 1923; Anderson, 1947b, 1956; Smith, 1968; Treagus, 1969, 1997; Thomas, 1979). However, Evans and Tanner (1996, 1997) speculated that the Kinlochlaggan succession contains an allochthonous, inverted and downward-facing upper Appin Group–lower Argyll Group stratigraphy, separated from the Grampian Group by a major structural discontinuity. In marked contrast, Piasecki and Temperley (1988b) equated the Kinlochlaggan succession with semipelites and metalimestones at the base of the Grampian Group that are exposed at Kincraig and Ord Ban (see the An Suidhe GCR site report).

In the steep belt, a gradational stratigraphical boundary is preserved locally between the Grampian Group and the Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation; the latter must therefore lie at the base of the Appin Group. The Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation is in stratigraphical succession above the Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation and, while the boundary between the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite and Coire Cheap formations is marked locally by c. 70 cm of platy psammite, this is not thought to represent a major tectonic discontinuity. The Kinlochlaggan Boulder Bed occurs locally in lenticular form on top of the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation and cannot on that basis be correlated with the Port Askaig Tillite (basal Islay Subgroup) and its equivalents.

The Aonach Beag Semipelite Formation is lithologically similar to the Loch Treig Schist and Quartzite Formation of the Glen Roy district, which also lies stratigraphically on top of the Grampian Group and is assigned to the Lochaber Subgroup. The Kinlochlaggan Quartzite Formation is lithologically similar to the Binnein Quartzite Formation in the Loch Leven area and hence it too is assigned to the Lochaber Subgroup. The Sron Garbh Semipelite Formation is correlated with the Leven Schist Formation of the Glen Roy district on the basis of lithological similarities, particularly its magnetic character, and its stratigraphical position. It is therefore assigned to the upper part of the Lochaber Subgroup although the correlation is tentative (Robertson and Smith, 1999).

Pale metalimestone in the Coire Cheap Formation, located above the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite, has a geochemical signature typical of the middle part of the Ballachulish Subgroup, while the remainder of the metalimestones have geochemical signatures similar to Blair Atholl Subgroup metalimestones elsewhere in the Grampian Highlands (Thomas, 1995; Thomas et al., 1997; Thomas and Aitchison, 1998). These correlations indicate that well-known segments of the Appin Group stratigraphy are missing from the exposed sections at this site. There is no representative of the Appin Quartzite and the uppermost parts of the Lochaber Subgroup are also absent. It is not known whether this is the result of non-deposition or erosion. Any erosion must have pre-dated deposition of the upper parts of the Ballachulish Subgroup, since this rests without a major structural discontinuity on the Kinlochlaggan Quartzite. Significant facies changes and thickness changes have been reported in the Appin Group in the South-west Grampian Highlands with possible uplift and erosion at the time of deposition of the Appin Quartzite (Litherland, 1970, 1980), supporting such interpretations.

Robertson and Smith (1999) argued that within the steep belt as a whole, component parts of the Kinlochlaggan succession show major onlap relationships. North of Laggan [NN 600 965], stratigraphical relationships show the progressive overstep of the Kinlochlaggan succession onto the Creag Meagaidh and Ardair formations and ultimately directly onto the Glen Banchor Subgroup. For 10 km along strike to the north-east of the River Spey, the entire Grampian Group is absent on the eastern limb of the Kinlochlaggan Syncline. This therefore represents one of the most significant stratigraphical breaks in the Grampian Highlands, but nowhere is it marked by an angular discordance or by exposed conglomerates. Based upon the regional stratigraphical considerations, Robertson and Smith (1999) argued for an original basin architecture in which the Glen Banchor Subgroup occured in a structural ‘high’ that formed the eastern wall of a west-facing basin during deposition of the Grampian Group and continued to influence depositional systems throughout Appin Group time. Metalimestones of the Blair Atholl Subgroup are the youngest parts of the sequence to overstep the Glen Banchor ‘high’.

11.3.2 Structural framework

Thomas (1979) interpreted the Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt as a fundamental root-zone because the major recumbent folds on opposite sides of the steep belt face in opposite directions i.e. to the north-west on the north-west side and to the south-east on the south-east side (see Stephenson et al., 2013a, fig 10a). In contrast, Temperley (1990) argued for a late structural development for the steep belt with folding and shearing superimposed upon a zone that had already experienced a protracted tectonothermal history.

The overall geometry of the steep belt is that of a major upright synform (Figure 5.31). The facing and vergence of small- and medium-scale structures indicates that much of the structural pattern developed during the first deformation phase, with few significant changes in architecture resulting from the subsequent deformation (Figure 5.4); the vergence of second-phase folds shows no large-scale systematic changes across the belt (Smith et al., 1999). The steep belt forms the boundary between contrasting structural domains with primary upright structures to the north-west and recumbent folding to the south-east. The original orientation of the structures in the steep belt has previously been envisaged as either upright (Anderson, 1947b, 1956; Thomas, 1979, 1980) or recumbent (Temperley, 1990; Evans and Tanner, 1996).

On the basis on the overall structural geometry and the stratigraphical relationships, Robertson and Smith (1999) argued that the Geal-charn-Ossian Steep Belt is a major composite synclinal structure focussed upon the Kinlochlaggan Syncline. According to their model, the steep belt originated as a primary feature located at the eastern margin of a major west-facing sedimentary basin in which more than 8 km of Grampian Group sediment had been deposited. This basin was adjacent to an intrabasin structural ‘high’ composed mainly of gneissose metasedimentary rocks of the Glen Banchor Subgroup and acting as the local basement to the Grampian and Appin group rocks. Major unconformities recognized at more than one stratigraphical level reflect onlap of the basin successions onto the ‘high’.

The primary major upright folds and associated slides of the steep belt developed when considerable shortening was focused along the basin margin during the Caledonian Orogeny (Figure 5.4). The deformation patterns were interpreted by Robertson and Smith (1999) as the result of buttressing and inversion of the depositional sequence against the more-rigid upstanding structural ‘high’. A similar origin has been suggested for the upright Stob Ban–Craig a’ Chail Synform which reflects deformation of the western edge of both the deep water Corrieyairack Subgroup basin and Appin Group half grabens (Glover et al., 1995).

11.4 Conclusions

The Aonach Beag and Geal-charn GCR site is of national importance for the way in which the complex Caledonian deformation pattern in a crucial central area of the Grampian Highlands can be related to the original geometry and subsequent development of early Dalradian sedimentary basins.

The site preserves excellent exposures of the stratigraphical relationships between the local Kinlochlaggan succession of the Appin Group and the underlying Grampian Group in a regional zone of steeply dipping rocks known as the Geal-charn–Ossian Steep Belt. The mountainous nature of the site is such that truly three-dimensional observations can be made of the structural geometry of the steep belt, which includes the complex upward-facing Kinlochlaggan Syncline and other complementary tight folds in its core.

The Geal-charn–Ossian Steep Belt occurs at the boundary between contrasting structural and stratigraphical domains. Distinct but coeval sedimentary successions in each domain responded in fundamentally different ways to later deformation, with primary upright structures to the west and recumbent structures to the east. The steep belt is a zone of primary major upright folds with associated slides, developed on severely attenuated fold limbs as originally stated by Thomas (1979). However, it is not a root-zone to divergent nappes as envisaged by Thomas, nor is it the product of a late monoform or late upright shearing as proposed by Temperley (1990). It occurs at the eastern margin of a thick composite sedimentary basin where deformation was focused against a footwall ‘high’. Subsequent deformation was then influenced by the distribution of half-graben fills and intrabasinal ‘highs’.

References