Chapter 8 The Hebrides Basin

Introduction

N. Morton

Geological setting

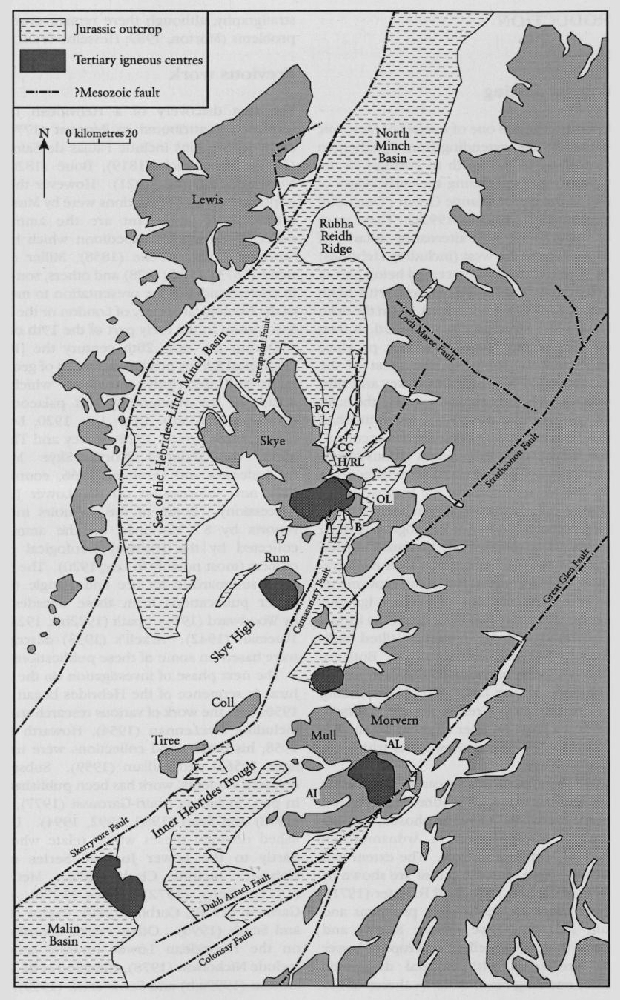

The Hebrides Basin is one of a series of Mesozoic extensional basins, extending from Spitzbergen and Greenland in the north to Portugal in the south, which evolved during the early stages of opening of the North Atlantic Ocean (Trueblood and Morton, 1991; Morton, 1992a). These were mainly half-grabens, with alternating polarity of faulted margin on the west (including Hebrides) or east. The Hebrides Basin ceased being part of the system after the Jurassic Period, with basin inversion in Early Cretaceous times, when the main tilted fault-block structures were formed. It then became part of the Thulean volcanic province during Palaeocene times so that most of the Jurassic sequence is intruded by dykes and sills. These caused only local baking, but near the main plutonic centres of central Skye, Ardnamurchan and Mull, thermal metamorphism has occurred.

Lower Jurassic rocks crop out on various islands of the Inner Hebrides and on some neighbouring parts of the western coast of the Scottish mainland

In some areas, particularly near the Palaeocene plutonic igneous centres, the Jurassic succession has been thermally metamorphosed, posing problems of interpretation in Ardnamurchan and parts of Mull and of Skye. The extent and effects of the Skye plutonic centre are shown by Thrasher (1992) and Taylor and Forester (1971). Elsewhere there are fewer such problems and in Mull, Morvern, Skye, Pabay, Raasay and Applecross there are excellent outcrops of Lower Jurassic sediments with normal diagenetic alteration, enabling reasonable syntheses of the stratigraphy, although there remain unresolved problems (Morton, 1989; Hesselbo et al., 1998).

Previous work

The first discovery of a Hebridean Jurassic sequence is attributed to Pennant (1774) and early descriptions include Faujas de Saint-Fond (1797), Macculloch (1819), Boué (1820) and Necker-de-Saussure (1821). However the most important early contributions were by Murchison (1829, more important are the ammonites collected during his expedition which became Sowerby types), Geikie (1858), Miller (1858), Bryce (1873), Judd (1878) and others, sometimes in correspondence for presentation to meetings of the Geological Society of London or the British Association in the early part of the 19th century.

During the early 20th century the [British] Geological Survey produced a series of geological maps and descriptive memoirs, which gave details of the stratigraphy and palaeontology (Peach et al., 1910, 1913; Lee, 1920; Lee and Bailey, 1925; Tyrrell, 1928; Richey and Thomas, 1930; the delayed North Skye Memoir by Anderson and Dunham, 1966, contributed little new information on the Lower Jurassic succession). Some of the memoirs included reports by S.S. Buckman on the ammonites collected by the [British] Geological Survey officers (most notably in Lee, 1920). The results were summarized by Lee and Pringle (1932). Other publications from these decades were by Woodward (1914), Spath (1922b,c, 1924), and Trueman (1942). Arkell's (1933) descriptions were based on some of these publications.

The next phase of investigation on the Lower Jurassic sequence of the Hebrides began in the 1950s with the work of various research students, including MacLennan (1954), Howarth (1956, 1958; his brachiopod collections were used by Ager, 1956a) and Hallam (1959). Subsequent research students' work has been published only in part, including Amiri-Garoussi (1977), Oates (1978) and Searl (1989, 1992, 1994). Unpublished doctoral theses which relate wholly or partly to the Lower Jurassic Series of the Hebrides include Clark (1970), McCallum (1971), Getty (1972), Oates (1976), Amiri-Garoussi (1978), Corbin (1980), Phelps (1982), and Smith (1996). Other recent contributions on the Hebridean Lower Jurassic sequence include Nicholson (1978), Hesselbo et al. 1998), Morton (1999a,b) and Farris et al. (1999).

These established the Hebrides as a significant area to be included in European or even global syntheses of Lower Jurassic stratigraphy, for example Hallam (1967a), Sellwood (1972), Getty (1973), Phelps (1985), Donovan (1990), Howarth (1992), Page (1992), Dommergues et al. (1994) and Hesselbo and Jenkyns (1998).

Syntheses and summaries of the Hebrides Jurassic System are given by Hudson and Morton (in Hemingway et al., 1969 — field guide), Cope et al. (1980a — on correlations), Hudson (1983), Morton (1987, 1989, 1992b on basin evolution), Hallam (1991), Bradshaw et al. (1992 — on palaeogeography), and Morton and Hudson (1995 — field guide). The setting and stratigraphical evolution of the Hebridean Lower Jurassic succession was described by Morton (1990) and in the broader context of British Lower Jurassic sequence stratigraphy by Hesselbo and Jenkyns (1998).

Stratigraphical framework

The Lower Jurassic rocks of the Hebrides are predominantly siliciclastics and the stratigraphical evolution of the area was different from that of Yorkshire, Somerset or Dorset. Therefore a different scheme of lithostratigraphical nomenclature

- For the Triassic (to lowermost Jurassic in the north) 'New Red Sandstone' continental red-beds, wider use of the name

Stornoway Formation (Steel and Wilson, 1975) was suggested by Morton and Hudson (1995). The type section is near Stornoway and the best Inner Hebridean section, at Rubha na' Leac on Raasay, is described by Morton and Hudson (1995). - The marine 'Rhaetic' (only in the south) was identified with and named the

Penarth Group (e.g. Cope et al., 1980a). The type section lies outside the Hebrides, but the best Hebridean section is in Gribun, western Mull, included in the Aird na h-Iolaire GCR site report. - The Hettangian to Lower Sinemurian succession of Mull and Morvern, previously classified with the Broadford Beds, is developed in alternating limestone–mudstone facies identical to the

Blue Lias Formation of south-west England Oates (1978) proposed using the same name,Blue Lias Formation , and this has been generally, though not universally, accepted. TheBlue Lias Formation passes laterally through intermediate sandy limestones and shales, seen in northern Ardnamurchan, south-west Raasay and Sconser in Skye into the lithologically varied unit traditionally called the 'Broadford Beds'. The type section lies outside the Hebrides, but details of the best Hebridean section are given in the Allt Leacach GCR site report: see also Hesselbo et al. (1998). - The name 'Broadford Beds' has been applied to the lower part of the Lower Lias since the 19th century, and subdivision into a lower more calcareous unit and a higher more siliciclastic unit widely used. Restriction in use of the name 'Broadford Formation' to only the lower unit was proposed by Hesselbo et al. (1998), but to avoid confusion the new name

Breakish Formation was introduced and defined by Morton (1999b). The type section east of Broadford is described in the Ob Lusa to Ardnish Coast GCR site repoxt. - The upper unit of the former Broadford Beds was included within an expanded Pabay (see below) Shale Formation by Hesselbo et al. (1998). However, Morton (1999a) argued that there is a basin-wide mappable lithological distinction (cf. Hesselbo et al., 1999) between the traditional 'Pabba Shales' and the upper unit of the 'Broadford Beds' and suggested the name

Ardnish Formation for the latter. This has been adopted by the [British] Geological Survey in the revised Broadford and Raasay 1:50 000 maps. The most important sections of the formation are described in the Ob Lusa to Ardnish Coast and Boreraig to Carn Dearg GCR site reports. TheHallaig Sandstone Member designated by Hesselbo et al. (1998) is used for the upper more sandy part of this formation. The type section of the member lies outside the GCR sites, but is described by Morton and Hudson (1995) and Hesselbo et al. (1998). - The 'Pabba Shale' was named after the Isle of Pabay, but the anglicized names used by the original authors were the versions then current. The original spelling has been used more recently by the Ordnance Survey (and other official bodies) and adopted as appropriate for lithostratigraphical nomenclature as

Pabay Shale Formation . The type section has not been defined, but is likely to be designated in the Boreraig to Carn Dearg GCR site. More sandy units within this formation are recognized by Hesselbo et al. (1998) as the Suisnish Sandstone Member (Skye, Raasay) and the Torosay Sandstone Member (Mull). The classic Allt Fearns section on the Isle of Raasay (Getty 1973; Page, 1992) is not included in a GCR site, but is described in Morton and Hudson (1995), while the section on Pabay is described by Hesselbo et al. (1998). - Similarly, the 'Scalpa Sandstone', named after the Isle of Scalpay, has been amended to

Scalpay Sandstone Formation , but the most appropriate type section is on the Isle of Raasay; see Howarth (1956) and the Rubha na' Leac, Cadha Carnach and Hallaig Shore GCR site reports. - The lower shaly part of the Upper Lias was named 'Portree Shales' in Lee (1920) after the capital town of the Isle of Skye (Portree, from Gaelic Port-an-Righ = King's harbour). This is retained as

Portree Shale Formation and the type section is defined and described in the Prince Charles' Cave to Holm GCR site report. - The shales pass up into the 'Raasay Ironstone', named after the Isle of Raasay, almost everywhere in the Hebrides where the strata are exposed, justifying recognition of a

Raasay Ironstone Formation even though it is frequently less than 1 m thick. The type section at the opencast mine on the Isle of Raasay is not included in any of the GCR sites, but is described in Morton and Hudson (1995). - The uppermost Lower Jurassic succession is classified lithostratigraphically as part of the

Bearreraig Sandstone Formation , notably theDun Caan Shale Member . This unit is described in the Middle Jurassic GCR volume under the Gualann na Leac and Bearreraig GCR site reports (Cox and Sumbler, 2002), and included here in the Cadha Carnach GCR site report.

The standard ammonite zonal and subzonal scheme for the Liassic of north-west Europe (Dean et al., 1961; modified in Cope et al., 1980a; and revised by Page, 2003) Is readily applicable to the Lower Jurassic sequence of the Hebrides, as shown by Hesselbo et al. (1998). Indeed two index species have their type localities in the Hebrides. Except for the middle and upper Toarcian successions, nearly all zones and subzones can be recognized in at least one locality. Some localities yield detailed faunal sequences and are of international significance for Lower Jurassic ammonite biostratigraphy, as indicated in the next section.

Locality descriptions

Only brief descriptive notes on the most important features or potential of the various localities are given here, for further details see the appropriate [British] Geological Survey memoir, or other references indicated. All the localities are shown on

Arran

The island of Arran is not strictly part of the Hebrides, but is included here for completeness. Two small poorly exposed outcrops of Lower Lias shales and decalcified mudstones are known, preserved by spectaculaz accident in Palaeocene vent agglomerates as a result of collapse of caldera walls. Ammonites of the Planorbis (Trueman, 1942) and Angulata zones occur in separate places, and elsewhere marine 'Rhaetic' shales and limestones and Upper Cretaceous chalk, thermally metamorphosed (Tyrrell, 1928). Comparisons may be made with Antrim in Northern Ireland where Lias up to Valdani Subzone is known in situ under Upper Cretaceous strata, and derived fragments from the Spinatum Zone and Lower Toarcian Substage are known from the Cretaceous basal conglomerate (Wilson and Robbie, 1966; 'Wilson and Manning, 1978). A greater lateral extent of at least Lower Liassic rocks than might otherwise be expected is proved here.

Mull

Outcrops of Lower (and the lower part of Middle) Jurassic rocks are mostly along the southern and eastern coasts of Mull, but in many areas, especially around Loch Don, the rocks are thermally metamorphosed to varying degrees. Exceptions include the remote outcrops of basal Lias in Gribun (Aird na h-Iolaire GCR site) and the important Upper Sinemurian to Lower Pliensbachian shore sections of Carsaig Bay (the original type locality of Ammonites Jamesoni Sowerby) (Oates, 1976; Hesselbo et al., 1998). Middle and upper parts of the Lias (and up to Upper Bajocian) occur in the Loch Don area (Lee and Bailey, 1925), but structural complications and thermal metamorphism sometimes make interpretation difficult. Higher parts of the Jurassic sequence are cut out by unconformity beneath the Upper Cretaceous sediments and Palaeocene basalt lavas (except for a surprising outcrop of Lower Kimmeridgian shales, see Morton, 1989). Isolated small outcrops of Lias occur in northern Mull.

Morvern

Lower Lias (up to Upper Sinemurian) occurs on both sides of Loch Aline on Movern, but the best sections are in streams to the east (MacLennan, 1954; Oates, 1976; Hesselbo et al., 1998), including the Allt Leacach GCR site. The Hettangian and Lower Sinemurian (to Lyra Subzone) successions are developed in classic

Ardnamurchan

There are excellent Lower Jurassic outcrops on both the northern and southern coasts of Ardnamurchan, but thermal metamorphism has limited the stratigraphical value of some. A transitional 'sandy Blue Lias' facies is noteworthy on the northern coast (Oates, 1976) and coral beds correlated with Skye. Outcrops in the Kilchoan area of Pabay Shale and Scalpay Sandstone formations are generally too metamorphosed to be informative, but there are important small outcrops of Toarcian strata on the coast, including the only recorded evidence for possible post-Bifrons Zone ammonites in the

Rum

No in-situ Jurassic sequence occurs on Rum because it forms part of a central basement ridge uplifted during Early Cretaceous times (the westward dip results in an outlier of Trias in the north-west). However a sliver of metamorphosed Jurassic limestones, presumably of the Blue Lias or Breakish formations, occurs in the ring-fault of the Palaeocene granophyric and ultrabasic plutonic complexes (Emeleus in Craig, 1983) and proves former continuity across the Camasunary Fault (see Morton, 1992b).

Skye

Outcrops of Lower Jurassic rocks occur in several parts of Skye, the most extensive forming a broad stretch between Broadford and Loch Eishort. The oldest beds dated by ammonites in this part of the Hebrides belong to the Angulata Zone, and are underlain by transitional 'Passage Beds' and the continental red-beds of the

Pabay

The low island of Pabay gives its name to the

Scalpay

The coastal outcrops of the 'name locality' of the

Applecross

The faulted Jurassic outlier in the remote village of Applecross is stratigraphically restricted to the Hettangian to lowermost Sinemurian

Raasay

The renowned Jurassic outcrops in the southern half of the Isle of Raasay owe their preservation, at least in part, to an overlying intrusive sheet of granophyre, but thermal metamorphism from this and other minor intrusions is fortunately limited. There are several superb stream, cliff and coastal exposures of all parts of the Lower Jurassic sequence. The contrast between the carbonate

Gruinard Bay

From the south side of Gruinard Bay to Loch Ewe there is a narrow strip of faulted Mesozoic rocks, but only limited outcrops of Lower Jurassic carbonates, presumed to be

Shiant Isles

The isolated Shiant Isles are composed mainly of dolerite intrusions, but baked Jurassic shales with Toarcian ammonites (

Stratigraphy

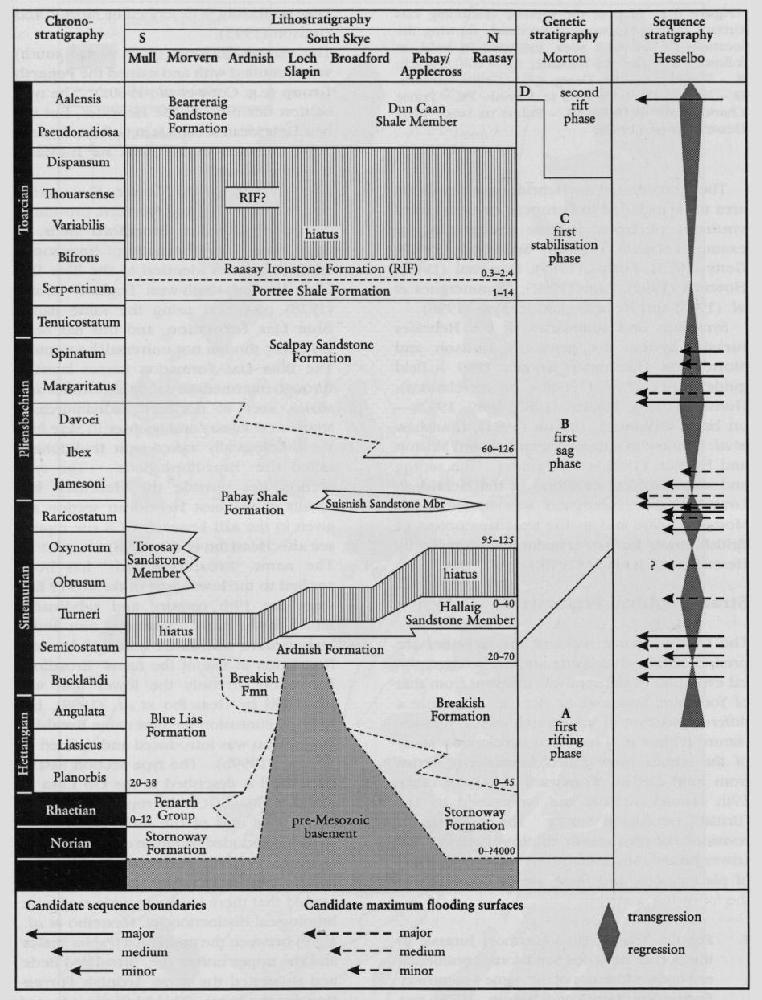

Two approaches to stratigraphical analysis of the Jurassic System of the Hebrides Basin have been employed by Morton (1987, 1989) and Hesselbo (Hesselbo and Jenkyns, 1998; Hesselbo et al., 1998), genetic stratigraphy and sequence stratigraphy. These were used to emphasize, respectively, tectonic and sea-level controls of stratigraphical evolution. These are generally complementary, but there are significant differences of interpretation

Genetic stratigraphy

Analysis in terms of genetic stratigraphical sequences (Morton, 1989) has resulted in the recognition of three major sequences, plus a fourth which begins with the Aalensis Zone at the top of the Lower Jurassic succession but is mainly Middle Jurassic. Sequence boundaries were defined at major changes of facies, sometimes associated with a hiatus, and each sequence was found to be characterized by a distinctive style of stratigraphical architecture (thickness and facies variation through the basin). Integration of this data with information from analysis of the subsidence history (Morton, 1987) has enabled interpretation of the dynamic stratigraphical evolution of the basin. The results for the Lower Jurassic succession are summarized below and in

Sequence A began with an episode of lithospheric extension causing fault-controlled (especially on the western margin) differential subsidence resulting in the deposition of continental red-beds (

Sequence B begins with a hiatus which can be identified but is of different ages in the various localities, although Morton's (1989) interpretation of a cliachronous hiatus is questioned by Hesselbo et al. (1998). In Mull, Morvern and Ardnamurchan parts of the Semicostatum and Turneri zones are missing below the

Sequence C is marked at the base by a sharp change of facies to dark organic-rich shales, the

Sequence D is mainly a Middle Jurassic sequence, so outside the scope of this volume. It is characterized by being very thick and highly variable in facies as well as thickness, indicating a new episode of renewed differential subsidence as a result of lithospheric extension. This began in very latest Early Jurassic times, because sediment accummulation recommenced with the top Toarcian Aalensis Zone, which is itself extremely variable; for example the thickness on Raasay increases from 9.1 m to 38.2 m over a distance of 3 km (Morton, 1965).

Sequence stratigraphy

Hesselbo et al. (1998) re-measured and restudied a number of the best Lower Jurassic sections in the Hebrides, publishing the first detailed measured successions for several decades. The stratigraphy was interpreted in the context of a wider study by Hesselbo and Jenkyns (1998) of Lower Jurassic secions in the Wessex, Bristol Channel and Cleveland basins as well as the Hebrides.

Four large-scale (second-order) transgressive–regressive cycles were recognized by Hesselbo et al. (1998), with boundaries in the

Palaeogeographical evolution

Onshore evidence proves that subsidence in the Hebrides Basin started in the Triassic Period, and highly irregular topography resulted in deposition of conglomerates and breccias, mostly of local derivation, in a series of alluvial fans and mass-flow deposits. These pass laterally into fluvial sandstones and floodplain mudstones, and development of caliche in semi-arid conditions was widespread and frequent (Steel, 1977). There is no direct evidence for dating, but a late Triassic (?Norian) age is likely. Arran was at this time part of a separately evolving sedimentary basin, with evidence of lacustrine deposition in a more varied environment. During the latest Trias (Rhaetian) the marine transgression spread northwards from the south-west of the British Isles, to give marine conditions in Arran and as far north as Mull.

Dating events at the beginning of the Jurassic Period is hampered by limitations of biostratigraphical evidence — no Planorbis Zone ammonites are known north of Mull, and Liasicus Zone ammonites (Franziceras) only from eastern Raasay (Morton, 1999b). Ammonites from the Angulata Zone (Schlotheimia) are rare but more widespread (Applecross, Skye, Ardnamurchan, Morvern, Mull). Integrating facies and biostratigraphical evidence from other fossil groups (e.g. bivalves) with the ammonite dating indicates that renewed transgression spread marine conditions farther north, to Morvern, Ardnamurchan and Raasay during early Hettangian times, and to Applecross probably in mid-Hettangian times. However, in southern Skye (Broadford area) an Angulata Zone ammonite occurs not far above the base of the

During the Semicostatum Zone there was a major change in the depositional environment, and final onlap of the topographic high related to the area of Cambro-Ordovician carbonates in the area north of Loch Slapin. In Raasay, Broadford, Loch Eishort, Mull and possibly Ardnamurchan, carbonate-dominated facies were replaced abruptly by ferrugineous association (Hallam, 1975) sandstones, siltstones and shales (

During Late Sinemurian times more uniform depositional environments occurred throughout the basin. The sediments were deposited on a mud- or silt-dominated shelf with local sand-bars (

The deepening event of the Early Toarcian Serpentinum Zone caused the establishment of deposition of shales (

There is no evidence from outcrops for any deposition having occurred during middle and most of late Toarcian times. Conversely there is evidence for only limited erosion in a few localities (e.g. Strathaird; see Morton, 1989), because the overlying

The top of the Lower Jurassic succession in the Hebrides is genetically part of the Middle Jurassic Series, with a lithospheric extension event beginning in latest Toarcian times (Morton, 1987) resulting in renewed subsidence in the Hebrides Basin and rejuvenation of hinterland topography resulting in influx of large quantities of coarse siliciclastic sediment to form the