Corstorphine Hill

Introduction

Corstorphine Hill is only 161 metres (531 feet) high. Its long low L-shaped wood-covered ridge rises above Edinburgh's western suburbs at the back of Edinburgh Zoo. On the summit is a tower dedicated to Sir Walter Scott, and two prominent communication pylons.

The shape of Corstorphine Hill, and the useful rocks found here, are due to geological processes: both long ago, in the Carboniferous Period (around 340 million years ago) and the much more recent processes of erosion.

This webpage, based on our printed leaflet, guides you around the hill to find different rocks, evidence of their use by people, and a variety of views. The hill is now a Local Geodiversity Site, having originally designated as a Regionally Important Geological Site in 2000. It is also a Local Nature Reserve. The area is managed by the City of Edinburgh Council Natural Heritage Service, assisted by the Friends of Corstorphine Hill.

Visiting Corstorphine Hill

Corstorphine Hill is 5km west of Edinburgh city centre, lying between Corstorphine Road and Queensferry Road. There are many access points around the hill and a good path network. It is easy to get to the hill by bus, with many services along the main roads to the north and south. Lothian Buses services 1 and 26 terminate at Clermiston, on the west site of the hill. There are two small car parks and on-street parking. There is no visitor centre or facilities. You can find out more about visiting from the Edinburgh Outdoor website (www.edinburghoutdoors.org.uk).

Safety and Conservation

The walks described below follow paths that may be rough in places. There are steep cliffs. The site is a Local Geodiversity Site and a Local Nature Reserve. The Friends of Corstorphine Hill are a group of people who have joined together to help look after the Corstorphine Hill area, for the benefit of people, animals, plants and the landscape. Their website has a lot of useful information and the group organises events including open days at Clermiston Tower.

Acknowledgements

The Corstorphine Hill leaflet was written originally by David McAdam and published in 2001. This edition produced by Lothian and Borders GeoConservation, a committee of the Edinburgh Geological Society, a charity registered in Scotland Charity No: SC008011.

© 2024 Lothian and Borders GeoConservation.

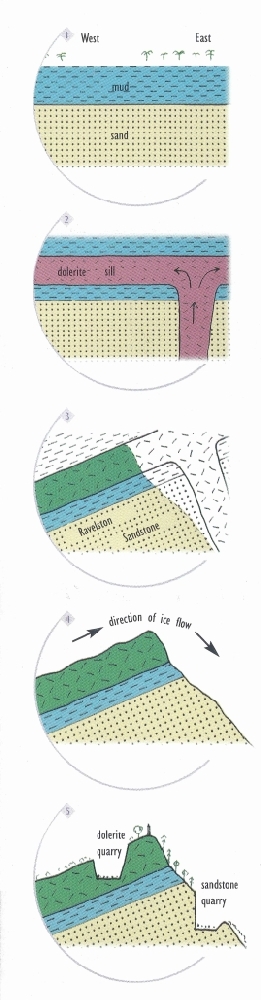

How Corstorphine Hill was formed (Figure 1)

- Around 340 million years ago, a large river delta covered this area. Beds of sand were laid down by a river the size of the modern-day Mississippi.

Silt and mud settled in tree-lined lagoons. - Gradual burial turned the sand into sandstone, the silt into flagstones. Volcanoes, such as Arthur's Seat, erupted around Edinburgh. At Corstorphine the molten rock (magma) did not reach the surface but was forced between the sedimentary strata to form a layer of igneous rock — a dolerite sill.

- The Earth's tectonic plates moved and built mountains. The still-buried rock of Corstorphine Hill was tilted to the west. Erosion began and continued for hundreds of million years to reveal the tough dolerite rock.

- Ice sheets flowed from the west during the last two million years. Laden with rocks, the ice sand-papered and moulded the top surface of the dolerite sill into glaciated pavements. To the east, steep slopes hide the softer sandstone and flagstone. The hill is a large 'roche moutonnée', a landform caused by ice erosion.

- After the ice melted, 15 thousand years ago, trees covered the steep east slopes of the hill. Gorse and scrub grew on the ice-smoothed dolerite of the gentler west slopes. People quarried the dolerite for roadstone and both the dolerite and Ravelstone Sandstone for building. The height of the hill has been utilised for a memorial tower and communication pylons, as well as for a cup-mark site in earlier times.

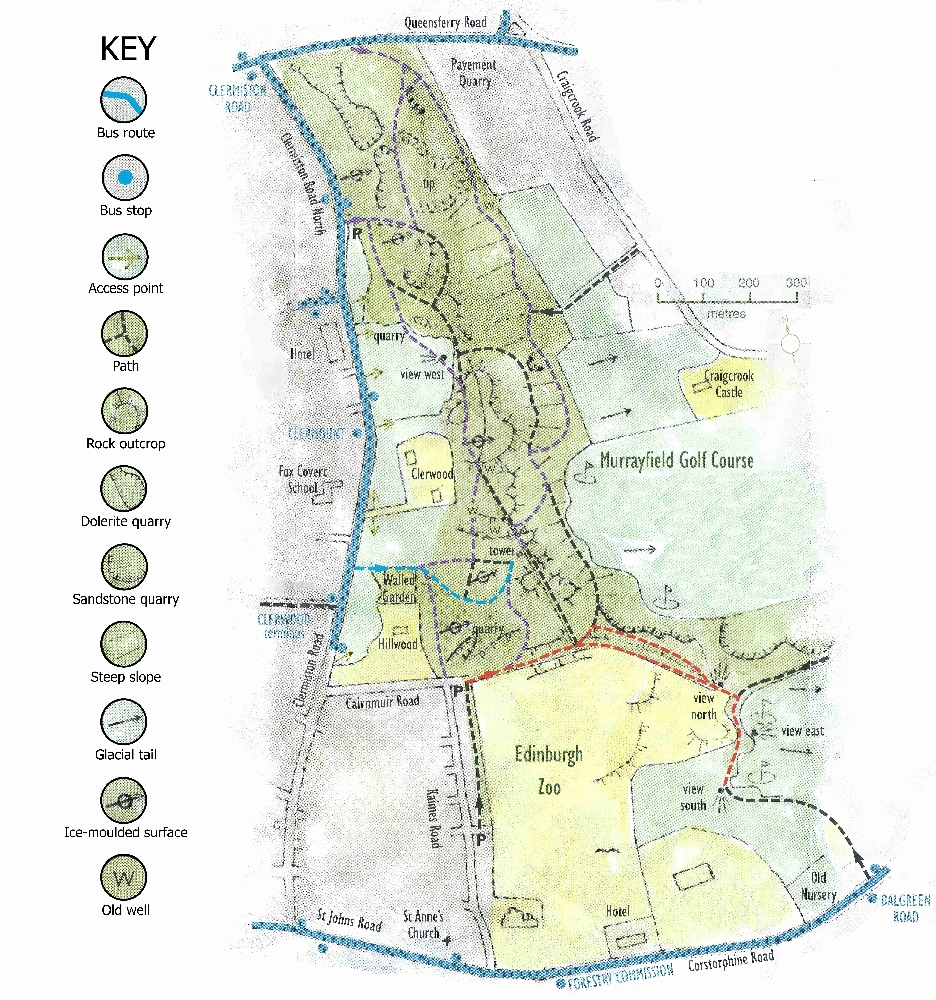

Walks around Corstorphine Hill (Figure 2)

'The Woods' is the local name for Corstorphine Hill and the extensive tree-cover is shown by darker green on the map. The woods are criss-crossed by many tracks and paths. It is easy to get lost!

North Ridge (purple route on map)

The top of the hill is the best place to see the glaciated pavements, and the tilted top of the dolerite sill that forms gentle slopes to the west. Several dolerite quarries have been cut into the sill. Take in the view-point to the west. The steeper eastern slopes conceal sedimentary rocks as in the Pavement Quarry and sandstone quarries. Look for fossil shells and plant stems in the loose debris.

Rest-and-be-Thankful (red route on map)

The ridge of Corstorphine Hill extends east along a glaciated pavement on the top of the ridge. The path goes between the Zoo and Murrayfield

Corstorphine Hill Tower (blue route on map)

From the Clerwood bus terminus, walk 100 metres along the path beside Clermiston Road. Cross and take the gated track, uphill past the old walled garden to the tower. The tower can also be reached easily from Kaimes Road or the Rest-and-be-Thankful.

Highlights

Corstorphine Hill Tower

The tree cover hinders views from Corstorphine Hill. Views from four good vantage points are illustrated. From the top of the tower, an even more magnificent all round view can be obtained.

The Walled Garden

Dolerite Quarries

Pavement Quarry

Fossils of mussel-like shells occur in loose blocks in the quarry. These molluscs lived in lagoons and also attached themselves to fragments of wood washed into rivers from trees along the banks.

Spectacular ice-smoothed surfaces on the western slopes

Boulder clay is the name given to the piles of moraine containing clay, stones, pebbles and boulders left behind by the ice 15 thousand years ago. This underlies the cultivated grass fields on the lower slopes. These have ridges aligned in the same directions as the glacial pavements.

Spoil heaps of large boulders were created by the quarrymen throwing unwanted blocks down the north-east slopes.

The Wider Geology

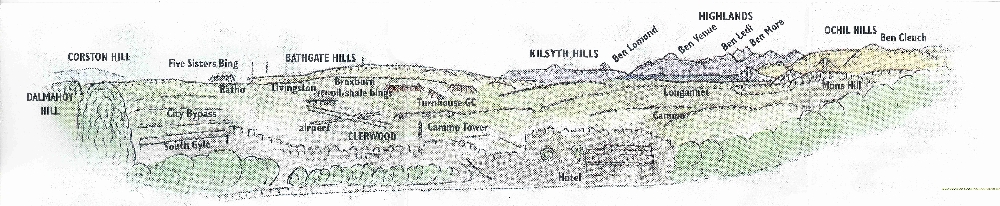

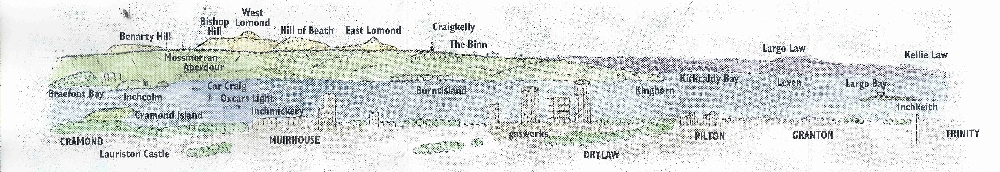

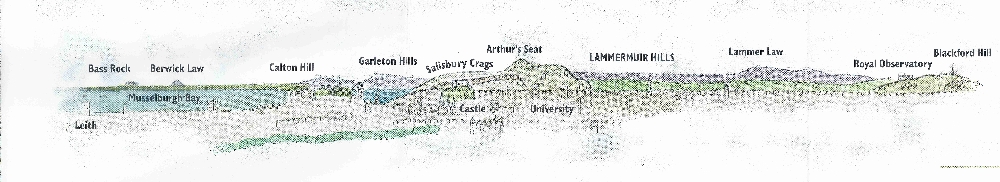

From Corstorphine Hill the full width of the Midland Valley can be appreciated. To the north-west, you can see the 600 million-year-old rocks of the southern Highlands, over 80km away. The rounded Lammermuir Hills of folded 500 to 400 million-year-old greywacke and mudstone — part of the Southern Uplands — lie 40km to the south-east.

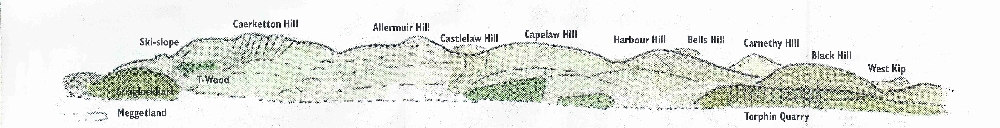

The hills in the Midland Valley are mainly hard igneous rocks. Blackford Hill, the Ochil Hills and the Pentland Hills are 400 million year old (Lower Devonian) andesite lava flows and ash layers, with sandstone and conglomerate. The other hills are of Carboniferous age, 360 to 300 million years old. Some are the sites of volcanoes with their basalt lavas, such as Arthur's Seat, the hills of Fife and East Lothian, and the Bathgate Hills. Others, such as Dalmahoy Hill, Cramond Island and Salisbury Crags, are dolerite sills like Corstophine Hill.

This are also signs in the landscape of how the geology has been used by people — including the red oil-shale bings in West Lothian, the remains of a century of extraction of hydrocarbons from rock.

Archaeology

Well-formed cup markings on a glacial pavement of dolerite were rediscovered in 1991. Their location offers wide views to the west. They are probably part of a sacred landscape of Neolithic or early Bronze Age (c3600-1500 BC), but their precise purpose remains tantalisingly unknown. At the end of the 19th century, quarrying uncovered remains of settlement debris: shells, bones, stone tools and pottery. (contributed by Anna and Graham Ritchie).

Panoramas

View west

View north

View east

View south