11 The Jurassic, Tertiary and Quaternary around Great Ayton and Roseberry Topping, Cleveland Hills

John Senior formerly Durham University and James Rose Royal Holloway, University of London

Purpose

To examine the Lower and Middle Jurassic sedimentary succession and the Tertiary Cleveland Dyke intrusion in the area around Great Ayton and Roseberry Topping; to investigate how this rock sequence, together with the late Quaternary glaciation of the area, controls the form of the landscape.

Logistics

This is a gentle full-day excursion covering 12.5 km. Numerous recognized paths and bridleways allow the route to be easily altered, shortened, lengthened or taken in reverse order. Park in Great Ayton, near the Tourist Information Office

Maps

O.S. 1:50 000 Sheet 93, Middlesbrough & Darlington; O.S. 1:25 000 Outdoor Leisure Sheet 26, North York Moors, Western Area (preferred); B.G.S. 1:63 360 Sheet 34, Guisborough.

Geological and geomorphological background

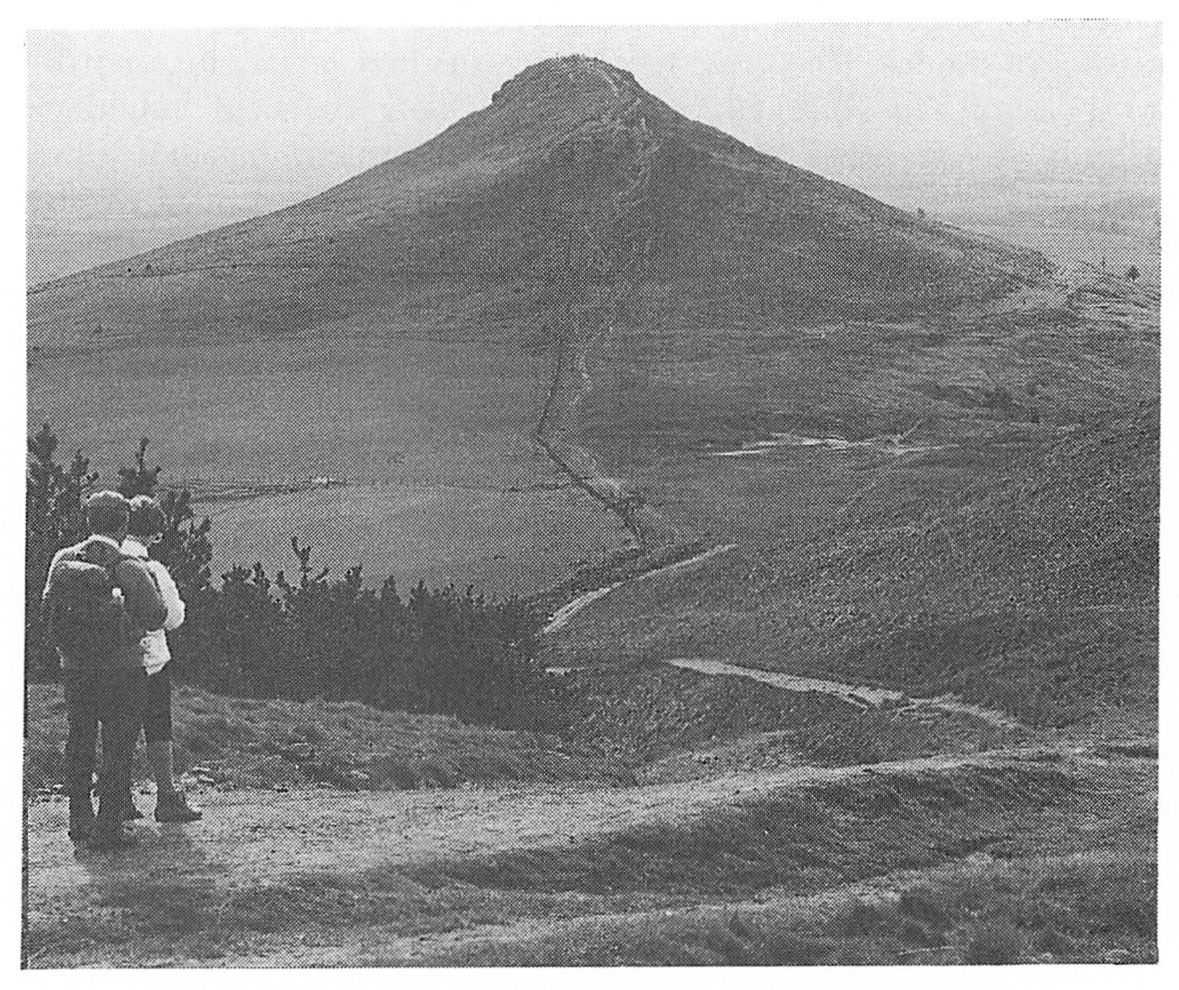

The area is on the western edge of the steep Cleveland Hills escarpment (Cleveland: in the Orkneyinga Saga Klifland or Clifa-land 'district of cliffs'), a classic piece of escarpment country with steep north- and west-facing slopes composed of softer Lower Jurassic rocks (in part Liassic shales) capped by more resistant Middle Jurassic sandstones. Roseberry Topping, a prominent landmark throughout the Cleveland Basin, is an erosional outlier, where the Middle Jurassic sandstone (

Although the Liassic sediments on the scarp slope are generally softer shales, the Middle Lias does include two more durable rock formations: the Staithes Formation and the

The intrusion of the Cleveland Dyke some 59 Ma ago has had a strong influence on the local landscape. This hard tholeiitic dyke (part of the dyke swarm from the Mull volcanic centre) forms the core of the west-northwest trending Langbaugh Ridge, visible from Great Ayton and Roseberry Topping. A local source of road metal, this dyke has been extensively quarried in the past too years or so. The dyke is about 25 m wide near Great Ayton and seems to have been regionally injected as a series of en echelon segments. In the Cliff Ridge Quarry near Great Ayton there is some evidence that the dyke was injected in leaves, separated by sediment screens; the Liassic dyke wall rocks have undergone incipient contact metamorphism.

Evidence for glaciation in the region takes the form of tills, glaciofluvial sands and gravels and lacustrine silts and clays on the lower slopes and in the valley bottoms. Additionally, glacial meltwater channels, located in anomalous positions without a drainage catchment, have been recognized and used as evidence to determine the slope of the glacier surface and the pattern of ice wastage. This evidence is attributed to the Dimlington Stadial of the Late Devensian Glaciation, when glaciers extended southward in eastern England to the region of the Wash, reaching their maximal extent about 17 000 14C yrs BP. Ice probably melted from the region sometime between about 16–15 000 14C yrs BP (Catt in Ehlers & Rose, 1991)

This ice failed to cover the higher parts of the Cleveland Hills, but was responsible for infilling the valley bottoms, reducing the relative relief of the region and significantly changing the valley bottom topography, producing many buried valleys throughout northeast England.

Although not glacierized during the Dimlington Stadial it is probable that the higher slopes were overridden by ice at some time earlier in the Quaternary, as resistant erratic pebbles have been recorded from the plateau surfaces of the Cleveland Hills. There is, as yet, no evidence to estimate the age of this earlier glaciation(s).

People have had a long-term influence on the landscape in this part of the Cleveland Hills. Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age peoples settled the region, helping to create the present-day 'grouse moor' landscape of the upland areas by forest clearance. Their presence is evidenced by well-defined ridge routes as well as numerous defensive sites, enclosures, field patterns, clearance cairns and burial tumuli. Monastic sheep farming created grange communities with associated field holdings, and medival iron smelting using local iron ores also added to the wealth of the Abbey or Priory. Sedimentary iron ore extraction (from the

Excursion details

From the Tourist Information Centre, Great Ayton

Locality 1 [NZ 563 114] , at the junction with the A173.

Look north to the very evident Langbaugh Ridge, the core of which is the Tertiary Cleveland Dyke. Differential erosion of the softer Lower Liassic sediments from around this dyke has resulted in this prominent feature which stretches west-northwest into the Tees Basin. Tills mask the bedrock on either side of the ridge. Langbaugh Ridge has been extensively quarried for roadstone

Continue up the A173 to the summit of the ridge and take the bridle road east-southeast towards Cliff Ridge Wood and Roseberry Topping.

Locality 2 [NZ 566 119]

Just before crossing the railway bridge, stop to contemplate the magnificent view of Roseberry Topping to the northeast

Locality 3 [NZ 570 118] –[NZ 576 116]

The deep ravines through this wooded ridge result from extensive extraction of the dyke rock for road metal. Large blocks of the tholeiite, containing large crystals (phenocrysts) of feldspar set in a fine-grained matrix, can still be seen scattered throughout the workings. In some areas of the south wall minor leaves of the dyke, with associated sediment screens, may still be viewed in situ. All the wall rocks of the dyke show incipient contact metamorphism and these more indurate sediments form the sheer walls and pinnacles. (This locality can be dangerous, with sheer drops masked by trees and shrubs; there is also the danger of falling blocks from the wall areas.)

The dyke has been intruded into Lower Jurassic sediments. Approaching from the west the first sediments encountered are the silty shales of the Ironstone Shales (Lower Pliensbachian; Upper

Eastwards, the sediments become more silty and eventually grade imperceptibly into the silts and sandstones of the shallower-water deposits of the Staithes Formation (Middle Lias; Upper Pliensbachian). It is difficult to view these sediments in situ as they often form the upper levels of the quarry ravines. However, numerous fallen blocks show these marine impure sandstones to be richly fossiliferous with common Middle Lias bivalves such as Pseudopecten,

Return westwards to the start of the ravine area and take a path to the right to join the public right of way through the woods to the north of the quarry area.

Locality 4 [NZ 572 118]

At the top of the hill are the remains of the winding house and incline for the mineral line from the Roseberry Ironstone Mines. Continue due east towards Airy Holme Farm (Airy = Norse/Irish for 'shieling', i.e. summer pasture residence) where a southeastward-sloping glacial drainage channel formed during the melting of the last ice sheet. Just before the first house, turn north-northwest up the marked right of way along the field boundary towards Roseberry Topping. Note the prominent bench feature between Roseberry Topping and Cliff Ridge Wood, formed by the sandstones of Middle Lias Staithes Formation

Under favourable conditions the continuation of the mineral line may be seen diagonally cutting the field to your left, crossing the path at

Continuing northeast towards Roseberry Topping, the path (at about 230 m OD) starts to skirt the eastern edge of the landslip and has been in part stepped using Middle Jurassic flaggy sandstones, some of which have small tridactyl theropod dinosaur prints on the top surfaces. Note the large and jumbled blocks of sandstone on the disturbed ground to the west. To the southeast are areas of vegetated abandoned quarries and isolated pits in the field nearby, where sedimentary ironstones of the

At the head of the landslip the fine cliff formed of trough cross-bedded sandstone (

Locality 5, Roseberry Topping [NZ 579 126]

On a clear day Roseberry Topping, capped by the Middle Jurassic sandstone outlier, affords fine views of the Eston Hills and Teesside to the north, the Cleveland Hills escarpment to the southwest, and Eskdale and the North York Moors to the southeast. The ridge formed by the Cleveland Dyke intrusion can be seen stretching out west-northwest into the Liassic and Triassic lowlands with their cover of glaciogenic sediments.

Walking east on the ridge path (Cleveland Way) between Roseberry Topping and Newton Moor you can see to the south uneven grassed terrain, the working areas (with remains of the mineral railway) associated with the Roseberry ironstone workings

Some 2 km to the southeast, at the same geographical and geological level, is the even larger area of disturbed ground of the Ayton Banks Mines. Here the overlying

Locality 6 [NZ 587 128]

Before the Cleveland Way reaches the edge of the escarpment it passes over a series of earthworks. Some of these are of recent origin — sandstone quarries for local walling. However one deeper excavation cutting north–south across the watershed may be a defensive ditch.

The route now follows the Cleveland Way southwards along the edge of the escarpment which is capped by deltaic sediments of the Middle Jurassic (

Locality 7 [NZ 593 119]

Here views may be had of the escarpment with a spring line at the junction between the sandstones and the underlying Upper Lias shales. A prominent quarry on the escarpment

At the northern edge of High Intake Plantation the route may be varied. Continue directly to Locality 9 via the conspicuous group of three cist burial chambers with associated enclosures

Locality 8 [NZ 600 115]

The quarry here is large and has been worked as a source of good building sandstone from one of the Middle Jurassic channel infills (

Leave the quarry by the rutted trackways that skirt the hill to the southwest. Pass by a very large Iron Age ditched rectangular enclosure and a smaller enclosure nearby

This pathway also passes a smaller sandstone quarry at

Locality 9 [NZ 594 112] -[NZ 594 111]

Where this minor track reaches the well-developed track near a small beck, follow the stream bed downhill. In the stream section thin-bedded sandstones of Middle Jurassic age are underlain by a thick sequence of shales. Some disturbed ground on this junction together with loose blocks of ironstone suggest that the

The track then passes through the col known as Gribdale Gate

Note that the tracks from the sandstone quarries head towards Great Ayton. A gentle downhill road leads back to the station or Great Ayton, with views of the Ayton Bank iron mines and Alum Shales workings on your left.